Understanding the Complexities of Gender Violence in Oromia, Ethiopia

Feature Commentary: “Gender-Based Violence: The Global War – A Survivor’s Call to Conscience”

By: Najat Hamza | January 5, 2026

Najat Hamza’s return to writing is not a quiet one. It is a roar of pain, a meticulously argued indictment, and a survivor’s manifesto. Her article, “Gender-based Violence: The global War against Women and Girls,” transcends a simple opinion piece. It is a forensic analysis of a global crisis, a psychological breakdown of domestic terror, and a deeply personal plea rooted in the specific soil of Oromia, Ethiopia. Hamza masterfully weaves the universal with the local, forcing the reader to see a worldwide epidemic through the devastatingly specific cases of Qanani and Ayyantu.

From “Women’s Issue” to Human Catastrophe: Reframing the Crisis

Hamza’s opening salvo is a crucial reframing. She immediately dismantles the marginalizing label of “women’s issue.” Her language is deliberate and expansive: a “global human-rights crisis,” a “public-health emergency,” a “social and economic catastrophe.” This terminology is strategic. It moves the problem from the periphery of societal concern to the center of our collective survival. By citing the WHO statistic—that staggering 1 in 3—she universalizes the experience, proving this is not confined by geography, wealth, or culture. The “global south and global north” both bear this stain. This establishes her authority; she is not speaking from parochial anger, but from a documented, planetary reality.

The Anatomy of Entrapment: Demystifying “Why Didn’t She Leave?”

The core of Hamza’s commentary is a brilliant, painful public service. She directly confronts the chorus of victim-blaming questions that inevitably arise: “Why did she stay?” She doesn’t just condemn these questions; she annihilates their premise with a clinical walkthrough of the cyclical mechanics of abuse.

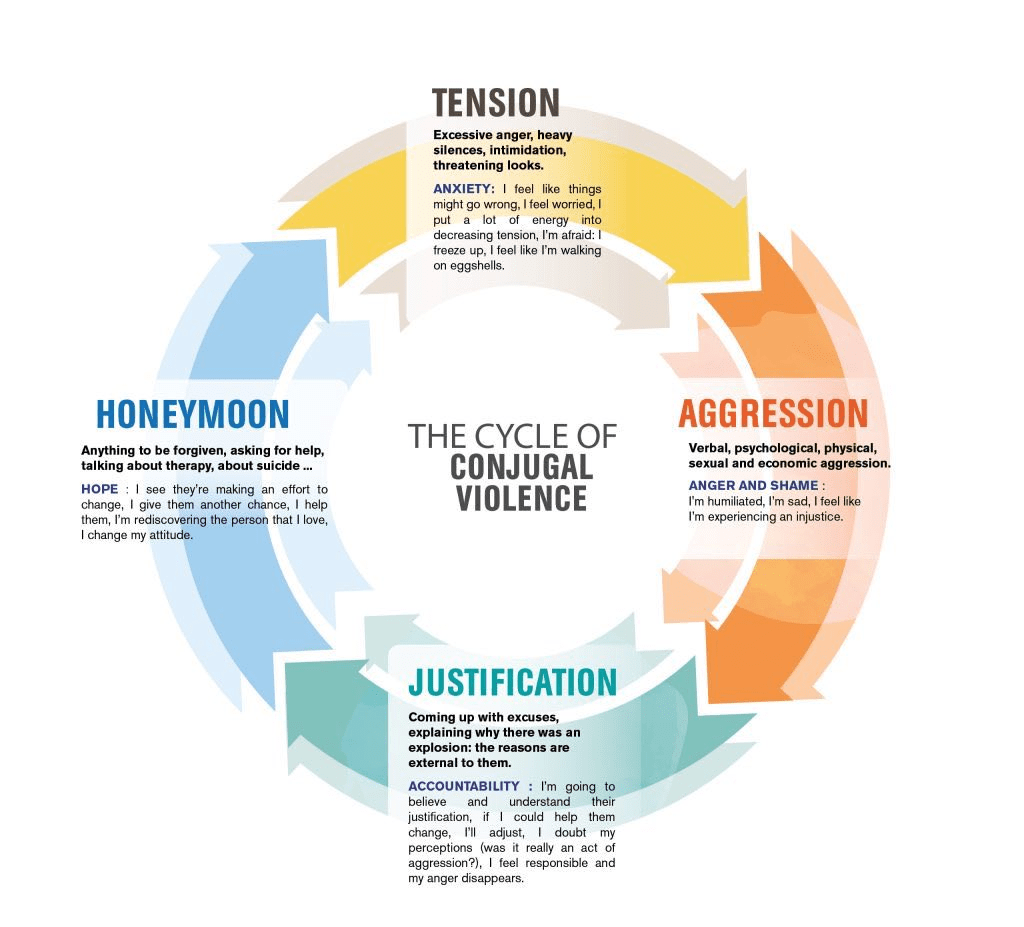

Her breakdown of the phases—Tension, Explosion, Justification, Honeymoon—is more than descriptive. It’s an education. She explains how violence is not the beginning, but the “completing act” of a long process of psychological and spiritual dismantling. The “honeymoon phase” is identified with chilling accuracy as the engine of entrapment, a “false sense of security” that is, in fact, a survival trap.

Most critically, she highlights the lethal paradox: “The most dangerous time for a woman… is when she decides to leave.” This single sentence is a devastating rebuke to simplistic solutions. It explains why leaving is not an act of simple courage, but a high-stakes gamble with life itself. The abuser’s ultimate tool, she argues, is not just the fist or the acid, but the “fear of retaliation and death” that freezes victims in place.

A Spotlight on Home: Patriarchy as a Justice-Denying System

While grounding her argument in global data, Hamza makes a powerful choice to focus on Ethiopia. Here, her analysis sharpens into a critique of systemic patriarchy. She moves beyond individual perpetrators to indict the “system built to protect men,” a system that “revictimizes” the dead and “forbids healing” to the living by “denying justice.” This is a crucial pivot from seeing violence as discrete criminal acts to understanding it as a culture-sanctioned phenomenon. The cases of Qanani (killed) and Ayyantu (disfigured, living without justice) are not presented as anomalies, but as logical outcomes of this system. They become symbols of a spectrum of suffering—from stolen life to a life sentenced to visible and invisible scars.

The Call: Men’s Accountability and the Crime of Silence

Hamza’s prescription is unambiguous and challenging. “The hard truth is that men must hold men accountable.” She calls out the gap between opposing violence “in theory” and tolerating it “in practice.” Her most potent moral charge is against complicity: “Silence is not neutrality. Silence is protection for the perpetrators.” This transforms every bystander, every relative who looked away, every community elder who urged reconciliation, into an actor in the tragedy. The “witnesses who choose silence for their comfort” are, as she states, “part of the problem.”

Her final, impassioned crescendo universalizes the victim again—she can be educated, powerful, traditional, of any class or color. “It can look like me, you… the daughter you love…” This is an empathetic bridge, a plea to see every woman as potentially vulnerable within the unequal architecture of our societies.

Conclusion: A Survivor’s Resolve

Najat Hamza signs off not just as a commentator, but as “A survivor !!!” This personal claim transforms the entire article. It is no longer just analysis; it is testimony. Her hashtags—#JusticeforQanani, #BreakYourSilence—are not slogans, but the distilled essence of her argument: memory and voice.

Hamza’s commentary succeeds because it is intellectually rigorous and emotionally resonant. It educates as it accuses, explains as it condemns. She provides the language, the framework, and the moral imperative to see gender-based violence for what it is: a pervasive war requiring not just individual compassion, but systemic rebellion and the relentless, vocal accountability of an entire society—starting with the men within it. Her return to writing is a gift of clarity and a formidable call to arms.

Posted on January 6, 2026, in News. Bookmark the permalink. Leave a comment.

Leave a comment

Comments 0