Monthly Archives: October 2022

Tigray has resisted Ethiopia’s far greater military might for two years – here’s why neither side is giving in

By Asafa Jalata

The Ethio-Tigray war started on 4 November 2020. For almost two years, the governments of Ethiopia and Eritrea – along with Amhara regional forces and militia – have waged war against Tigray’s regional government and society.

Tigray is a tiny ethnonational group that makes up about 6% of Ethiopia’s population of 121 million. Yet, it has been able to hold off well-armed military forces.

As a sociologist who has written extensively on the cultures of nationalism in the region, I have studied the deep and complex roots of this conflict. I believe that understanding its history is key to comprehending how Tigray has developed the resolve to hold off a far greater military might than its own.

Neither the leaders of Ethiopia and Eritrea nor those of Tigray accept the principles of compromise, peaceful coexistence or equal partnership. According to their political cultures, winners take all. It’s zero-sum politics.

The war today

The Ethiopian National Defence Force captured Mekelle, Tigray’s capital city, on 28 November 2020. The Ethiopian army was helped by Eritrean and Amhara military forces.

Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia’s prime minister, congratulated his army and allied forces for what looked like a quick victory.

However, the Tigrayan Defence Force made a tactical retreat. Its troops moved to rural areas and used guerrilla operations supported by war veterans. This strategy demonstrated Tigray’s effective fighting force, which was first developed in the 1970s.

As a result, eight months after the start of the war, Tigrayan troops returned to their capital. The Ethiopian army retreated from Mekelle and other cities.

Tigrayan troops then invaded the neighbouring Afar and Amhara regions, and almost made it into Finfinnee (Addis Ababa) in November 2021. However, they soon retreated to their region.

Since then, Tigrayan forces have controlled and administered most of Tigray.

The Ethio-Tigray war has been devastating for Tigrayans. They have faced mass killings, military bombardment, rape, looting and the destruction of property. The conflict has denied them access to food, electricity, telecommunications, medicine, banking services and other necessities.

Yet they support the Tigray Defence Force. To understand why requires a deeper reading of Ethiopia’s history.

A complex history

Two Amhara emperors and one Tigrayan emperor laid the foundation of the modern imperial state of Ethiopia. The first emperor of Abyssinia/Ethiopia was Tewodros (1855-1868). He was followed by Yohannes IV (1872-1889) of Tigray and then Menelik II (1889-1913).

Under Menelik II, the Amhara state elite replaced Tigray’s leaders. They made Tigrayan society a junior partner in building the Ethiopian empire.

But Tigrayan nationalists believe their society was the foundation of the Ethiopian state.

Read more: Ethiopia’s war in Tigray risks wiping out centuries of the world’s history

In the last decades of the 1800s, the Ethiopian empire expanded from its northern core of Tigray and Amhara by colonising the Oromo and other ethnonational groups.

It established slavery, the nafxanya-gabbar system (semi-slavery) and the colonial land-holding system by taking the land of conquered people.

The nafxanya (gun-carrying settlers) elite – led by the Amhara – dislodged the Tigrayan elite from Ethiopian state power. Tigray was pushed to the periphery of an Amhara-dominated society. This created political rivalry between the two groups.

The status and living conditions of the Tigrayan elite and people deteriorated. This, along with several wars in the region, aggravated political, economic and social problems.

Accumulated grievances and many forms of resistance produced the Tigray People’s Liberation Front in 1975. It aimed to liberate Tigrayans from Amhara-led governments. This helped develop Tigrayan nationalism.

Tigray’s two nationalisms

Tigrayans maintain two forms of nationalism.

The first promotes Tigrayan autonomy, self-reliance and development.

The second is Tigrayan Ethiopianism. This theoretically maintains Ethiopia’s current geopolitical boundary, with its decentralised political structures where different population groups have some autonomy.

After building military power in the 1980s, Tigrayan elite dominated other ethnonational groups, particularly the Oromo, the empire’s largest ethnonational group.

Between 1991 and 2018, the Tigrayan elite controlled state power and the political economy. The Tigrayan elite created a pseudo-democracy. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front was the mover and shaker of the Ethiopian state.

The Oromo expressed their collective grievances with this political arrangement through the struggles of the Oromo Liberation Front. The Qeerroo/Qarree (Oromo youth) movement got involved between 2014 and 2018. This eventually dislodged Tigrayan leadership from Ethiopian central power in 2018.

Abiy was a member of the Oromo People’s Democratic Organisation, a subsidiary political party of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front. The Tigrayan Front, alongside its allied organisations, elected Abiy as Ethiopia’s prime minister in April 2018. He later turned on his support base.

Once he came to power, Abiy and his allies believed they wouldn’t stay in control if they did not destroy Tigrayan and Oromo nationalists. These were symbolised by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, the Oromo Liberation Front and the Oromo youth movement.

Zero-sum politics

Tigrayan and Amhara elites express and practice Ethiopianism differently.

The Amhara elite dominated Ethiopia from 1889 to 1991. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front overthrew them in 1991.

The wealth and experience Tigrayan elite accumulated over nearly three decades increased their national organisational capacity. This has helped them in the current war.

The Oromo have rejected the dominance and tyranny of both these groups. They have carried out their liberation struggle.

Abiy and his Amhara collaborators are fighting Tigrayans, Oromos and others to control Ethiopian state power. Their winning the war in Tigray and Oromia would allow the Abiy regime to continue a modified version of Ethiopia’s pre-1991 policy.

For Tigrayans, losing this battle would be equivalent to losing political power and returning to victimisation, poverty and the threat of annihilation.

Uncertain future

Given their complicated political history, reconciling the central government and the Tigrayan regional government is challenging. Even if these two groups negotiate a peace deal, conflict will continue if the Oromo are left out of the process.

If Tigray and Oromia’s political problems aren’t correctly understood and resolved, conflicts will continue until the collapse of the Ethiopian state.

This language was banned in Ethiopia just 30 years ago. Now, it’s being taught at Stanford

Oct. 20, 2022, 11:30 p.m.

Afan Oromo, a native language of Ethiopia, is being taught at Stanford for the first time this fall as a part of the Stanford Language Center’s African and Middle Eastern Languages Program (AMELANG) offerings.

Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie banned Afan Oromo from being spoken, taught, or administratively used in the country in order to subdue the Oromo people and culture in 1941. After the ban was lifted in 1991, a push to give new life to the language began in and beyond Oromia and Ethiopia, led by native-born and diaspora Oromians, as well as non-Oromians. This push has now reached Stanford’s campus.

Among Stanford’s sizable East African student population, Saron Samuel ’25 along with Eban Ebssa ’25 told The Daily they sought to connect more with their heritage and put in a special language request last winter to get Afan Oromo added as a class. While their request was initially denied, they were told if they got at least one more interested student, the class might get funding. The special languages petition allows students to work with the university to add courses on less popularly taught languages.

Samuel sprang to action: “I sent the form in multiple group chats, reached out to people I knew would be interested in taking the class and posted on social media,” she said.

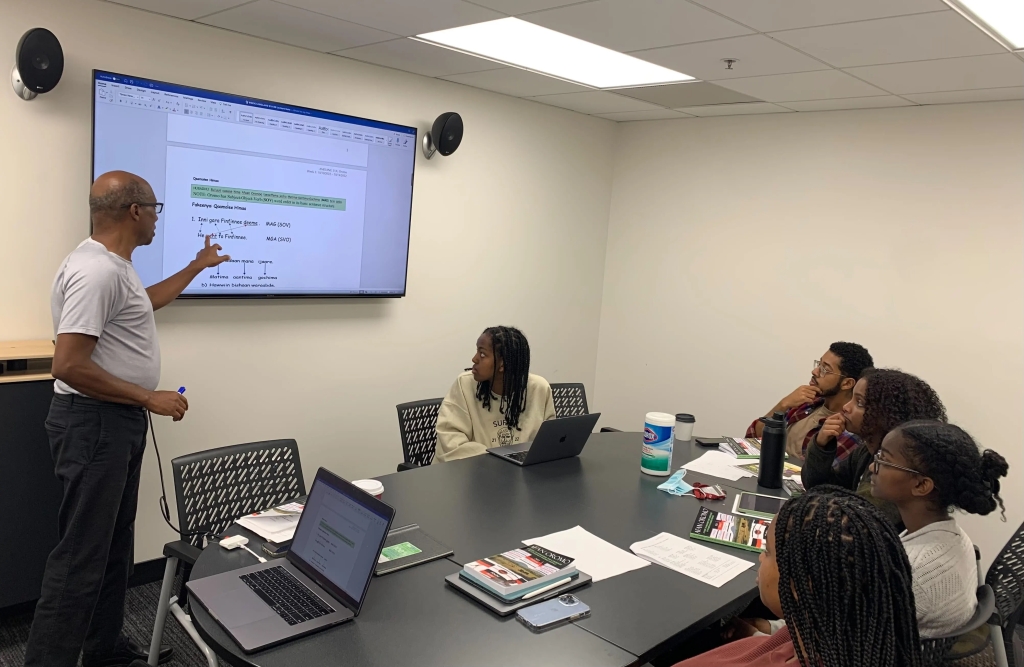

When the two had three more students commit to the class, the AMELANG Program expedited funding and hired a new lecturer, Afan Oromo teacher Belay Biratu, during the summer.

The University was able to add the course after a generous contribution from the Center for African Studies and in response to student requests, according to Coordinator of Stanford’s AMELANG Program, Khalil Barhoum. Afan Oromo is offered in a three-course sequence this year and will be the third Ethiopian language to be taught at Stanford, along with Amharic and Tigrinya.

Biratu told The Daily that he first learned the language secretly in the ’80s. He and other interested learners would meet in secret to explore the language. Although he was eventually caught teaching it to younger students and was punished severely for his actions, Biratu said he believes it was worthwhile, because he now gets to continue to teach the language and culture to those who seek it.

“In general, my view on teaching Afan Oromo is about doing justice to the culture. It is not against anyone, or any group. It is about doing justice to the people who are using this language as their mother tongue,” he said. “It is my passion and honest conviction that teaching language is doing justice to human culture.”

Biratu began this quarter’s class with an introduction of the sounds in Afan Oromo. Unlike English, Afan Oromo is a phonetic language and pronunciation is integral to its mastery, he said. He continues by teaching vocabulary, grammar and other foundational blocks of language-learning.

Biratu and his students consider themselves to be “pioneers who are paving the way at Stanford” for a greater appreciation and utilization of Afan Oromo.

Hawi Abraham ’24 said she has been petitioning the Languages Department to add Oromo since her freshman year, but the petition was never successful until now. Like Samuel and other students, she sought to learn the language to connect with her heritage and her family.

“My grandma only speaks Oromo, and not knowing the language was blocking me from this connection with her in many ways,” she said.

Abraham said she was never able to learn the language because of the lack of resources. She recalled a time when her Bay Area community tried to mount an effort to offer a course in the language, but there were no teachers or materials available.

“That’s why when I got into Stanford I knew this was one of my only chances to finally learn,” Abraham said.

Abraham said that due to the language’s half-a-century ban, there’s a palpable sense of enthusiasm and pride, as well as triumph, in the classroom. “Every time I walk into class, there’s a genuine excitement in the air to get it right and make our communities proud,” she said. “My parents never got the chance to learn Oromo in school, so every time I walk into class, I am so grateful for the opportunity that I am given, that many were not afforded.”

“Every time I learn something new, I call my family and share it with them,” she added. “I want to show them that the youth are not giving up on their culture, we’re fighting for it.”

“I am now learning Oromo and Amharic, and hopefully Tigrinya in the future,” Samuel said.

Today, the language is widely recognized, as the most spoken language in Ethiopia and the third most spoken language in Africa, and it is the lingua franca of the Oromo region. Because the ban ended only three decades ago, Ethiopian universities and institutions are now working to standardize and teach the language. Biratu hopes Stanford will join the effort.

Feyera Hirpa, a native Oromian and current chairman in the Northern California Oromo Community, said he is excited about the addition of the new class at Stanford.

“The community is just so proud because Afan Oromo is now being taught at Stanford, one of the world’s best universities,” Hirpa said. “I hope, and share this hope with many members of the community, that this is the beginning of something large.”

Biratu shared similar sentiments: “When this kind of thing happens, the Ethiopian community is so happy, it has been a dream come true,” he said. “We are just so happy for Stanford.”

DHS Designates Ethiopia for Temporary Protected Status for 18 Months

Release Date: October 21, 2022

WASHINGTON – Today, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced the designation of Ethiopia for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for 18 months. Only individuals who are already residing in the United States as of October 20, 2022 will be eligible for TPS.

“The United States recognizes the ongoing armed conflict and the extraordinary and temporary conditions engulfing Ethiopia, and DHS is committed to providing temporary protection to those in need,” said Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro N. Mayorkas. “Ethiopian nationals currently residing in the U.S. who cannot safely return due to conflict-related violence and a humanitarian crisis involving severe food shortages, flooding, drought, and displacement, will be able to remain and work in the United States until conditions in their home country improve.”

A country may be designated for TPS when conditions in the country fall into one or more of the three statutory bases for designation: ongoing armed conflict, environmental disaster, or extraordinary and temporary conditions. This designation is based on both ongoing armed conflict and extraordinary and temporary conditions in Ethiopia that prevent Ethiopian nationals, and those of no nationality who last habitually resided in Ethiopia, from returning to Ethiopia safely. Due to the armed conflict, civilians are at risk of conflict-related violence, including attacks, killings, rape, and other forms of gender-based violence; ethnicity-based detentions; and human rights violations and abuses. Extraordinary and temporary conditions that further prevent nationals from returning in safety include a humanitarian crisis involving severe food insecurity, flooding, drought, large-scale displacement, and the impact of disease outbreaks.

This will be Ethiopia’s first designation for TPS. Individuals eligible for TPS under this designation must have continuously resided in the United States since October 20, 2022. Individuals who attempt to travel to the United States after October 20, 2022 will not be eligible for TPS under this designation. Ethiopia’s 18-month designation will go into effect on the publication date of the forthcoming Federal Register notice. The Federal Register notice will provide instructions for applying for TPS and an Employment Authorization Document (EAD). TPS applicants must meet all eligibility requirements and undergo security and background checks.

Source: https://www.dhs.gov/news/2022/10/21/dhs-designates-ethiopia-temporary-protected-status-18-months