Daily Archives: January 28, 2026

The Legacy of Obbo Mama Argo: A Community’s Guiding Star

The Milk of Human Kindness: On Losing a Local Legend Like Obbo Mama Argo

By Dhabessa Wakjira

True community is rarely built in grand gestures announced with fanfare. More often, it is woven in the quiet, repeated acts of welcome that happen after dark, in the glow of a porch light, in the simple offering of a cool drink. The passing of a figure like Obbo Mama Argo of Seattle reminds us that the mightiest pillars of a diaspora are often the most humble, their legacy measured not in headlines, but in the cherished, personal memories of a generation.

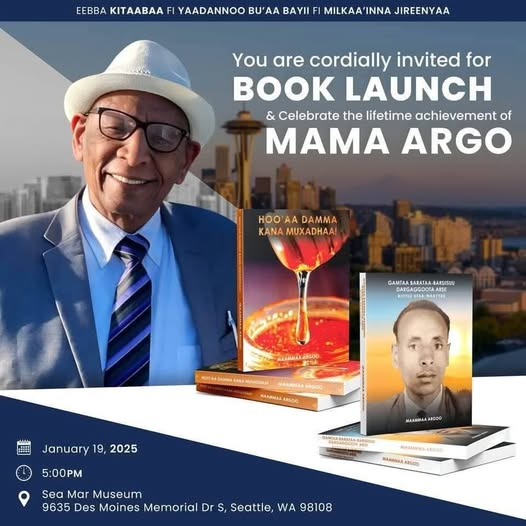

News of his departure arrives, as the community member writes, with “great sorrow.” But the obituary that follows is not a formal listing of titles—though he certainly earned them as a founding pillar of the Oromo Soccer Federation and Network in North America (OSFNA) and a selfless public servant. Instead, it is something more powerful: a flood of sensory memory, a testament to a man whose impact was felt in the intimate, daily fabric of life.

“I can’t think of anyone who was more selfless or whose contributions are more undeniable,” the tribute begins, anchoring his legacy in collective agreement. For over twenty years in Seattle, the writer explains, “we grew up looking up to his guidance and the love he had for Oromos.” Here is the core of it: he was a local north star, a constant reference point for a community finding its way in a new land.

Then comes the defining anecdote, the story that paints a clearer picture than any official biography ever could. “Back in those childhood days… every evening after soccer, we would go to his house and drink milk.” From this simple, nurturing act emerged his most beloved title: “Abbaa Aannanii” – the Father of Milk.

This name is a masterpiece of community poetry. It speaks of sustenance, of care, of a home that was always open. It speaks of a man who understood that building a community isn’t just about organizing tournaments or holding meetings; it’s about feeding the youth, literally and spiritually. His house wasn’t just a residence; it was a post-game refuge, a cultural waystation where ties were strengthened not through rhetoric, but through shared cups and shared presence.

The tribute makes a profound point about gratitude: “This blessing was a great reward that the Seattle community received from him. Receiving it was timely.” Abbaa Aannanii performed his essential role precisely when it was most needed—during the formative years of a community’s establishment. His gift was his unwavering, predictable kindness.

And so, the writer issues a crucial, poignant reminder: “It is necessary to say THANK YOU to people like him while they are still alive.” We are often so good at eulogizing, at weaving beautiful galatoomaa in hindsight. But the true challenge is to offer that gratitude in real-time, to honor the living pillars before they become memories.

Obbo Mama Argo’s story is a universal one. Every community, every neighborhood, has its Abbaa Aannanii—the person whose door is always open, whose quiet support forms the bedrock. His passing is a deep loss precisely because his contribution was so profoundly human. He built a nation not through pronouncements, but through poured cups of milk; not just through organizing soccer, but by ensuring the children who played it were nourished, welcomed, and loved.

His legacy is the warmth of that remembered milk, the strength of the bonds forged in his living room, and the enduring model of a patriotism expressed through radical, open-hearted hospitality. We extend our deepest condolences to his family, the Seattle Oromo community, and OSFNA. In mourning him, may we all be inspired to see, appreciate, and thank the quiet pillars in our own midst, while the light on their porch is still on.

An Unseen Architecture: The Passing of a Pillar and the Foundation He Leaves Behind

An Unseen Architecture: The Passing of a Pillar and the Foundation He Leaves Behind

By Maatii Sabaa

A community, especially one woven across a diaspora, is an intricate architecture. We most easily see its public face—the vibrant festivals, the spirited tournaments, the collective statements. But the integrity of the entire structure, its ability to stand firm across distance and time, depends on a different kind of element: the hidden pillars. These are the individuals whose work is not in the spotlight, but in the scaffolding; whose legacy is not a single dramatic act, but the relentless, humble labor of holding things together.

The recent passing of Obbo Mama Argo is the quiet removal of such a pillar. The condolences flowing to his family, the Seattle Oromo community, and the Oromo Soccer Federation and Network in North America (OSFNA) speak to a loss that is deeply personal yet irreducibly public. He is remembered with the profound titles that form the bedrock of any strong society: a devoted patriot, a loving family man, a selfless public servant. But it is the specific mention of his founding role in OSFNA, and his three decades of support for it, that reveals the true nature of his contribution.

To found an organization like OSFNA is to do more than start a sports league. It is to recognize that for a dispersed people navigating the complexities of a new world, identity needs a living, breathing, communal space. A soccer tournament becomes more than a game. It is an annual pilgrimage, a temporary capital, a network of kinship and care. It is where the next generation meets the old, where news is exchanged, where culture is performed, and where a scattered nation gathers to feel whole.

For three decades, Obbo Mama Argo helped build and sustain this sacred space. This was not a ceremonial role. It is the unglamorous work of logistics, diplomacy, fundraising, and quiet encouragement. It is resolving disputes, securing fields, comforting losses, and celebrating victories that extend far beyond the final whistle. It is the work of a builder who understands that the structure—OSFNA—is not an end in itself, but a vessel for preserving something infinitely precious: a sense of belonging.

His type of patriotism is the most essential kind. It is not the patriotism of grand rhetoric, but of concrete action. It is the patriotism that shows up, year after year, to ensure the community has a place to play, to connect, to be Oromo together in a foreign land. This “selfless public service” is the very glue of diaspora survival.

In mourning him, the community confronts a poignant truth. We often celebrate the visible leaders—the speakers, the stars, the officials. But the true resilience of a people is forged by those like Obbo Mama Argo, whose life’s work was to be a reliable constant, a foundational node in the network. His absence creates a silence that is less about noise and more about stability; a space where his once-steadfast presence used to be.

The greatest tribute to such a man, therefore, is not just in the tears shed, but in the continued strength of the architecture he helped build. It is in the ongoing vibrancy of OSFNA, in the unity of the Seattle community, and in the commitment of new generations to step into the supporting roles he exemplified. To honor Obbo Mama Argo is to understand that the most enduring monuments are not made of stone, but of sustained, loving effort. His legacy is etched in every game played, every connection made, and in the enduring sense of home he helped construct for a nation far from its geographic one.

Galatoomi, Abbaa Argo. Your foundation holds.