Daily Archives: February 1, 2026

Remembering the Past: Key to Oromo Self-Determination

Feature Commentary: On History, Fear, and the Unfinished Work of Liberation

By Maatii Sabaa

February 1, 2026

A specter haunts the discourse around the Oromo struggle for self-determination: the fear of history. Not the fear of making history, but the fear of speaking its full, unvarnished truth. A persistent notion suggests that to revisit the complex, often painful narrative of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) is to court chaos, to sow discord, and ultimately, to abandon the ongoing struggle. This perspective, often implied if not directly stated, holds that dwelling on the past is counterproductive.

This is a profound and dangerous miscalculation.

To argue that examining our history—with all its sacrifices, schisms, and strategic crossroads—has no place in the current struggle is to build our future on a foundation of amnesia. It is to disrespect the very martyrs in whose name we claim to act. The journey of the OLF, from its intellectual germination in the early 1970s, its formal establishment in 1973, and the articulation of its political program in 1976, is not a relic to be shelved. It is the origin story of a modern political consciousness. The subsequent decades of immense sacrifice—of targeted killings, imprisonment, and exile of its intellectuals and heroes—were the bloody ink with which chapters of resistance were written. The bittersweet victory of 1991, which broke the back of the Derg but saw the dream of Oromo liberation deferred, is a pivot point every contemporary analysis must contend with.

The internal fractures, the political alliances within the four-party coalition of 1991, the subsequent marginalization, and the difficult choices faced in the 1990s are not scandalous secrets. They are critical data points. They explain why the OLF found itself back in the bushes, in a “no-choice” scenario, fighting to keep a promise made to its fallen. To ignore this is to ignore the root causes of the very cycles of conflict and resistance that have characterized the past thirty years.

The claim that today’s generation, which has demonstrated formidable political maturity through movements like the #OromoProtests (Finfinnee DFS/Gadaa system is not the correct term here, replaced with the widely recognized hashtag) and the Qeerroo mobilization, would be destabilized by an honest reckoning with history is an insult to their intelligence. It is a paternalistic logic that assumes they cannot handle the complexity that shaped their present. We see remnants of old guard mentalities attempting to replay 30-year-old scripts, causing needless friction, and we are told to look away for the sake of unity. But unity forged in silence is fragile; unity built on a shared, honest understanding is unbreakable.

Therefore, speaking our history—the full history of a people’s resistance against successive repressive systems—is not separate from the struggle. It is an essential organ of it. Our history is our primary weapon against systemic alienation. When we surrender its narrative out of fear, we disarm ourselves intellectually and spiritually.

The central question for every individual invested in this cause today must not be, “How do I avoid offending powerful sensibilities?” It must be: “What is my role in ensuring the ultimate sacrifice of our heroes was not in vain?” For those who mistake gossip, character assassination, and sowing despair among the ranks as revolutionary action, a reckoning is due. True revolutionary duty lies in disciplined organization, in studying and adapting the strategic frameworks of our forebears to today’s realities, and in building upon—not abandoning—their foundational goals.

My recounting of history is not a wish to return to yesterday. It is an act of gathering all the pieces of our story so we can understand the puzzle of our present. Yes, we must celebrate every hard-won gain at the national level. But we must also be clear-eyed: without a deliberate, collective, and honest effort to address the core, unresolved question of Oromo national self-determination, those gains will remain incomplete and vulnerable.

The final struggle is not just against a visible enemy; it is against the forgetting, the fear, and the fragmentation of our own story. To remember completely, to analyze courageously, and to speak truthfully is, itself, a revolutionary act.

The Final Struggle is to End Subjugation!

Victory for the Oromo People!

Restoring Haramaya: A New Era for Tourism and Environment

Feature Commentary: Haramaya’s Return – From Symbol of Loss to Engine of Growth

For years, the name Haramaya evoked a profound sense of loss and environmental grief in Ethiopia. The haunting image of a vast, cracked lakebed where a major body of water once thrived became a national symbol of ecological mismanagement and the devastating consequences of environmental neglect. The primary culprit, as experts consistently pointed out, was siltation and pollution—a slow-motion disaster unfolding over 17 years.

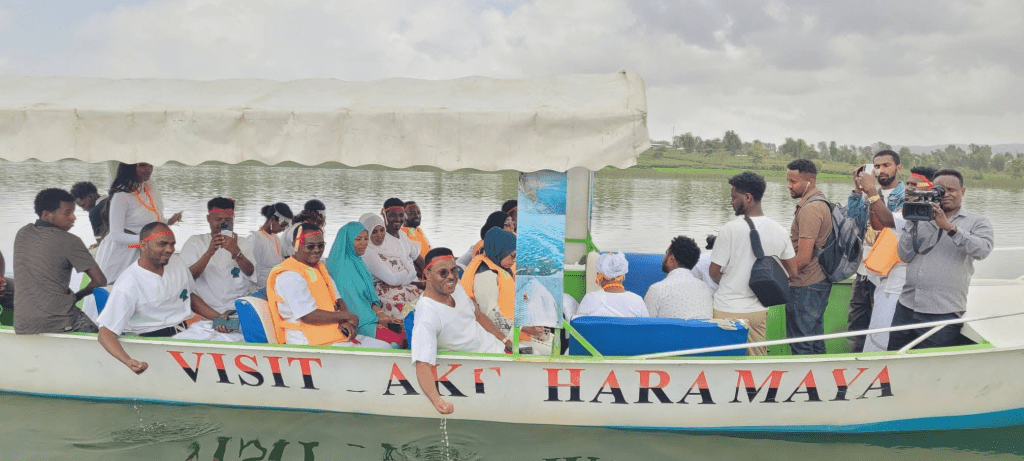

However, a remarkable story of restoration and reimagining is now being written. As of late 2025/2026, Haramaya is not just back; it is being strategically positioned as a cornerstone for economic development and a premier tourist destination. This isn’t merely a recovery; it’s a metamorphosis.

The catalyst for this shift is a multi-faceted, concerted effort spearheaded by the Oromia Regional State. As highlighted by officials like Culture and Tourism Bureau Head Jamiila Simbiruu and Mayor of Mays City Dr. Ifraha Wazir, the mission has moved far beyond refilling the lake. The goal is to systematically develop and promote Haramaya’s immense historical and natural potential. Having already achieved regional recognition, the focus is now on elevating it to a site of national significance.

The restoration itself is a testament to community-powered environmentalism. The lake’s return is credited to intensive rehabilitation works, including silt clearance and watershed management, combined with the transformative “Asheara Magarisaa” (Green Legacy) initiative. This involved the active participation of communities from 14 surrounding villages, turning a top-down directive into a grassroots movement for revival.

But the vision extends far beyond the shoreline. Authorities report that the lake’s volume and fish stocks are increasing year on year. Crucially, the perimeter is being secured, cleaned, and developed to unlock its full economic potential. An initial access road has already been completed, and a larger recreational project is underway along the banks, signaling a commitment to creating sustainable infrastructure for both visitors and the ecosystem.

Perhaps the most significant shift in strategy is the move from purely government-led action to a model seeking robust public-private partnership (PPP). Dr. Ifraha explicitly noted that unlocking Haramaya’s full potential requires significant investment from the private sector. This is already materializing, with 19 tourism-focused investment projects approved, nine of which are set to be built directly on the lakefront.

The ambition is grand. As the largest lake in Eastern Ethiopia, Haramaya is poised to serve not just Mays City but a wide region. It is envisioned as a major revenue generator and a source of employment, particularly for the youth. Its influence is rippling outward, with the production of lakeside ornamental plants now supplying major cities like Dire Dawa and Jigjiga.

In summary, the narrative around Haramaya has been fundamentally rewritten. It has transformed from a cautionary tale into a beacon of ecological recovery and smart economic planning. From being a place Ethiopians mourned, it is now a site they can visit and enjoy. With intensified efforts to enhance tourist services and attract more domestic and international visitors, Haramaya stands as a powerful testament to what can be achieved when environmental restoration is seamlessly integrated with community engagement and visionary economic development. The lake that was lost has been found again, and it is now working for its people.