A Generation Passing: On the Legacies of Tussoo and Legesse

By Alemayehu Diro

Commentary

When two intellectual pillars of a people fall within a span of two months, it is not merely a moment for mourning. It is a historical event, a closing of a distinct chapter, and a profound test of a community’s capacity to be its own custodian. The passing of Professors Hamdeessaa Tussoo and Asmarom Leggesse represents precisely such a rupture. Their collective departure compels a reckoning not just with what has been lost, but with the monumental, unfinished work they have bequeathed.

These were scholars whose lives formed a powerful dialectic. Professor Tussoo, a foundational pillar of the Oromo Studies Association, wielded the scalpel of political science and history. His works—The Survival of Oromo Nationalism, The Oromo Problem and U.S. Foreign Policy—were acts of intellectual demystification, systematically dissecting the structures of domination and articulating the “Oromo question” on a global stage. His was the scholarship of confrontation, dismantling the “mythical Ethiopia” brick by academic brick.

Professor Legesse, in contrast, wielded the archeologist’s brush and the anthropologist’s deep gaze. His seminal works, Gadaa: Three Approaches to the Study of African Society and Oromo Democracy, were acts of majestic reconstruction. He did not just study an indigenous system; he resurrected its sophisticated architecture for the world, proving that democracy, checks and balances, and rule of law were not Western imports but African traditions practiced for centuries. His was the scholarship of reclamation, restoring a pillar of cultural and philosophical identity.

Together, they formed a complete intellectual front: one deconstructing the prison, the other rebuilding the home. Their shared mission was to arm the Oromo people with the two most powerful weapons against erasure: a true history of their oppression and a true understanding of their innate capacity for self-governance.

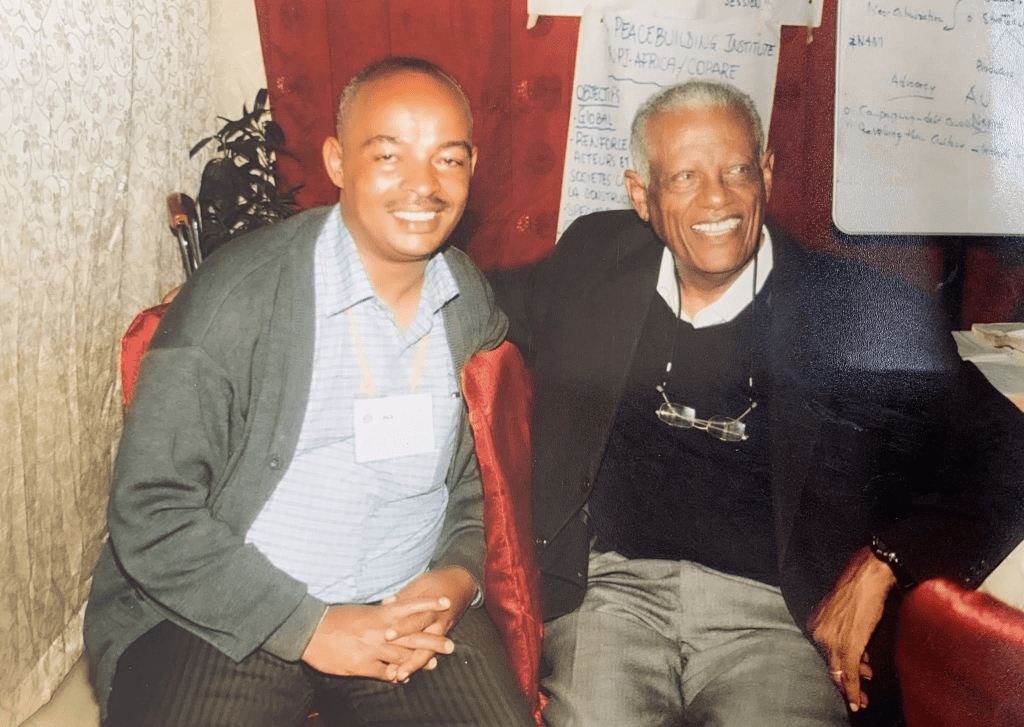

The personal recollection of Professor Legesse in forums like the GPAAC meetings is illuminating. His insistence on discussing Gadaa even while representing Eritrean civil society was not mere academic interest; it was a lifelong vocation. His profound insight—that Oromo unity (tokkummaa) is not an abstract goal but a lived reality woven through the exogamous fabric of their social life—reveals the depth of his understanding. He saw the political in the cultural, the unity in the everyday, long before it became a slogan.

This is why his unfinished agenda, shared in private conversation, is not a personal footnote but a collective mandate. His five visionary projects—from translating Oromo Democracy into Afaan Oromoo to developing a Gadaa-based educational curriculum—are not merely items on a to-do list. They are the blueprint for the next phase of intellectual sovereignty. They represent the critical work of moving from explaining a system to institutionalizing its wisdom for future generations.

Herein lies the true challenge and the call to action. The passing of this generation of intellectual giants—Tussoo, Legesse, and before them, figures like Sesay Ibsaa—creates a daunting vacuum. But it also presents a clear, urgent charge. Their legacies are not passive monuments to be admired; they are active toolkits to be used. The responsibility now falls squarely upon institutions like the Oromo Studies Association, universities within Oromia, and a new generation of scholars to pick up the threads of these unfinished projects.

To honor Professor Tussoo is to continue the rigorous, unflinching analysis of power structures. To honor Professor Legesse is to build the educational systems and cultural institutions that can breathe continuous life into the Gadaa philosophy. Their work was, in essence, a single project: the restoration of Oromo agency in history and in the future.

Their physical voices are silent, but their scholarship shouts. The question now is who will answer. The highest tribute to these “giant scholars” will not be found in eulogies alone, but in the determined, collaborative effort to complete the monumental tasks they envisioned. To ensure their history remains dignified, their memory indestructible, and their contributions timeless, the work must continue. Bol’a isaanii daadhiin haa guutu—may the earth rest lightly upon them. But may their unfinished work weigh heavily upon us, guiding our hands and sharpening our minds in the struggle they so brilliantly illuminated.

Posted on February 6, 2026, in News. Bookmark the permalink. Leave a comment.

Leave a comment

Comments 0