General Damisse Bulto: The Forgotten Eagle of Ethiopia’s Skies

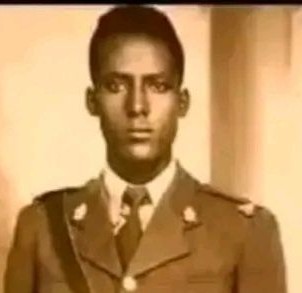

Personal Profile

Who was General Damisse Bulto? 💔

The question lingers, suspended in grief and memory. For those who knew him, he was a son of Ada’a Berga, a herdsman turned warrior, an aviator who painted his nation’s future across African skies. For those who have forgotten—or were never taught—he is a ghost in the military archives, a name erased from official histories, a body moved in secret.

This is his story.

From the Pastoral Plains

General Damisse Bulto Ejersa was born in 1926 in Ada’a Berga District, West Shewa, to his mother Adde Ayyee Jiraannee and his father Mr. Bultoo Ejersa. From childhood, he knew the weight of responsibility. While other boys played, young Damisse tended his family’s cattle, moving through grasslands that would later seem impossibly distant from the jet streams he would one day command.

But the open fields that raised him also gave him his first taste of horizons. A boy who watches the sky from the earth learns to dream of flight.

When he reached the appropriate age, Damissae traveled to Finfinne to study at the Medhanealem School. It was there, in the capital’s classrooms, that a military recruitment announcement changed everything. The Makonnen School was calling for cadets. Without informing his family, the young man enlisted—and stepped onto a path that would define the rest of his life.

The Making of a Makonnen

Three years of intensive training transformed the cattle herder’s son into a disciplined officer. By 1946, as Lieutenant Colonel, he received orders that would carry him far from Ethiopian soil.

The Korean Peninsula was aflame. The Cold War’s first hot conflict had drawn nations from across the globe into its crucible. Ethiopia, under Emperor Haile Selassie, committed troops to the United Nations forces. Among them was Damissae Bultoo—a young commander representing his ancient empire on a distant battlefield.

He served with distinction. He returned alive. He completed his consecration ceremony. And then his nation called again.

Ethiopia had no air force to speak of. The Emperor, modernizing his military, sought to build one from the cockpit up. Damissae was selected for training in Israel, where he learned the arts of aerial warfare from one of the world’s most capable air arms. He returned home a pilot—and soon, commander of the famed “Flying Leopard” squadron.

Wars and Recognitions

The 1950s and 1960s were decades of fire. When Somalia challenged Ethiopia’s territorial integrity, General Damisse took to the skies. In 1955 and again in 1957, he flew combat missions against Somali forces, his Leopards drawing blood across the Ogaden skies.

Emperor Haile Selassie took notice. The young man from Ada’a Berga, who had once watched clouds from cattle pastures, now received medals and commendations from the Lion of Judah himself. He rose through the ranks: Colonel in 1969, Brigadier General in 1972, Major General in 1977.

Each promotion marked not merely personal advancement but the trajectory of a man who had dedicated his entire existence to the defense and dignity of his nation.

The Dream of Oromia

Yet General Damisse’s patriotism was not uncritical. He loved Ethiopia—but he also saw its failures. He served the empire—but he also dreamed of liberation for his own people.

When the Derg seized power, when Mengistu Hailemariam’s Red Terror washed Ethiopian cities in blood, General Damisse made his choice. He would not merely serve. He would resist.

The plan was audacious, befitting an airman accustomed to thinking in three dimensions. On the morning of December 8, 1981, Mengistu was scheduled to depart for East Germany. General Damisse and his co-conspirators intended to shoot down the dictator’s aircraft—or, alternatively, divert it to Eritrea and capture the leader himself. A single blow to decapitate the Derg and open the path for Oromia’s liberation.

But conspiracies breathe thin air in authoritarian states. Fellow air force officers, when approached, hesitated. Some refused outright. The plot faltered, then collapsed. No missile was fired. No aircraft was diverted. No dictator fell.

The dream of an Oromo political order, forged in that moment of daring, remained unrealized.

The Exile and the Grave

What follows is contested, obscured, deliberately forgotten.

What is known: General Damisse was killed. The commander of the Flying Leopards, the veteran of Korea and Ogaden, the man who had received medals from an emperor’s hand, died at the hands of fellow officers—or of the regime they served.

His body was initially interred in Asmara, within the compound of the Catholic Church of St. Isteqs. Eritrea, then still part of Ethiopia, received the fallen general in silence. His grave marked nothing more than a name, a date, a vanished life.

But even the dead are not beyond the reach of politics.

Years later, after Eritrea had separated, after Asmara had become foreign soil, General Damisse’s remains were exhumed. They traveled south, across the border his squadron had once defended, back to the capital city where a cattle herder’s son had first dreamed of flight.

Today, they say, he rests in Finfinne. Within the compound of St. Joseph’s Church. A man displaced even in death, his final resting place known to few, visited by fewer still.

What Remains

General Damisse Bulto left no political testament. No memoirs. No public confessions or private apologies. He left only the record of his service—the medals, the missions, the promotions—and the whispered memory of a plot that failed.

To Ethiopian military history, he is an embarrassment: a decorated commander who turned against the state. To Oromo nationalists, he is a martyr: a patriot who understood that love of nation and love of people could not be separated. To his family, he is simply gone—a father, a grandfather, a name spoken in prayers.

And to the young men and women of Ada’a Berga, who still tend cattle beneath the same skies he once watched, he is a question without answer.

Who was General Damisse Bulto?

The cattle know. The grass knows. The wind that moves across the West Shewa highlands remembers the boy who became an eagle.

But the archives are silent. The grave is quiet. And the dream he died for remains, like his body, displaced—waiting for a nation that has not yet decided whether to claim him.

💔

The author acknowledges the family of General Damisse Bulto and surviving members of the Ethiopian Air Force who provided information for this profile, many of whom spoke on condition of anonymity.

Posted on February 13, 2026, in Finfinne, Information, News, Oromia. Bookmark the permalink. Leave a comment.

Leave a comment

Comments 0