Author Archives: advocacy4oromia

Strengthening the Oromo Struggle: A Generational Charge

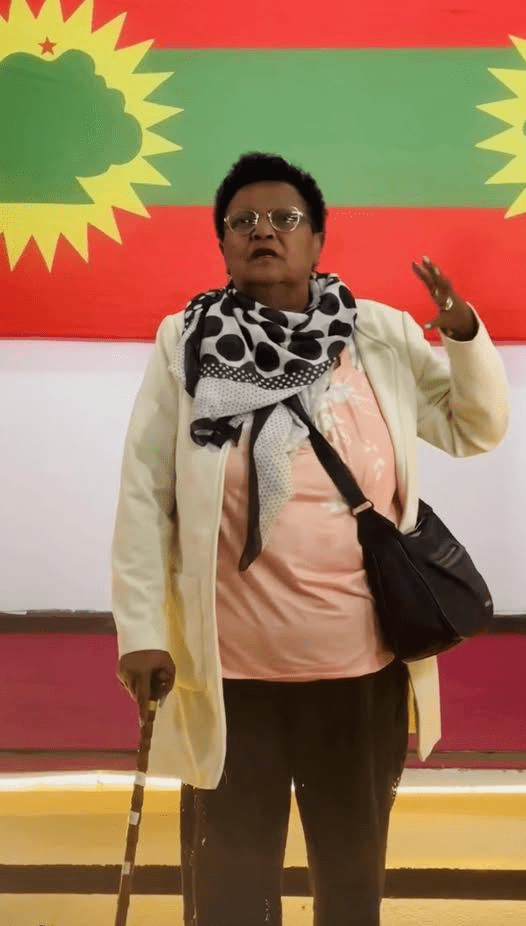

FEATURE NEWS: “Steadfastness Is Our Leaders’ Mark” – A Legacy Charge from Veteran Oromo Fighter Jaal Dhugaasaa Bakakkoo

A powerful and symbolic passing of the torch was highlighted this week as activist Raajii Gudeta Geleta shared a personal charge received from revered Oromo elder and liberation stalwart, Jaal Dhugaasaa Bakakkoo. The message, simple yet profound, cuts to the core of the movement’s enduring philosophy: “Strengthen yourself for the goal you stand for. Do not let this trust (amaanaa) wither.”

The directive, shared by the activist, transcends mere encouragement. It is framed as a sacred covenant between the generations of the struggle. Jaal Dhugaasaa, a former senior executive of the Oromo Liberation Army (WBO/OLA) and a foundational figure in the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), is seen as a living repository of the movement’s history and its original kaayyoo (objective). His words are therefore treated not as casual advice but as a veteran’s strategic and moral bequeathal.

“This trust (amaanaa) is the entire struggle itself,” explained Raajii Gudeta in contextualizing the message. “It is the sacrifice of those who came before us, the dream of freedom they carried, and the responsibility they placed in our hands. When Jaal Dhugaasaa says ‘do not let it wither,’ he is speaking to every Oromo, especially the youth, to guard the purity and focus of our objective.”

The activist’s commentary elaborated further, emphasizing the non-negotiable direction of the journey. “The starting point and destination of the Oromo struggle—sovereign statehood—is not something that turns back until it is realized.” This statement reinforces the movement’s foundational claim to self-determination and dismisses any notion of tactical retreat from its ultimate goal.

Most striking was the framing of resilience itself as a defining leadership trait. “Steadfastness (cephoominni) of the Objective is the hallmark of our leaders,” Raajii Gudeta stated. In a political landscape often marked by fragmentation and shifting allegiances, this highlights an internal metric for legitimacy within the community. True leadership, by this measure, is defined not by fleeting popularity but by unwavering fidelity to the kaayyoo, even under immense pressure.

The event underscores a recurring theme in Oromo political discourse: the vital link between historical memory and contemporary action. Figures like Jaal Dhugaasaa Bakakkoo serve as both inspiration and accountability mechanisms. Their public presence and private exhortations are constant reminders that today’s political calculations are judged against the backdrop of decades of sacrifice and a clearly stated destination.

This reported exchange is more than a personal anecdote; it is a microcosm of the movement’s ongoing dialogue with its own soul. It reaffirms that the Oromo struggle views itself as a generational relay race, where the sacred amaanaa of sovereignty is the baton, and cephoominni—unyielding steadfastness—is the only acceptable posture for those who dare to carry it. The message from the elder is clear: the path is set, the trust is given. Now, guard it, strengthen yourselves, and do not waver.

Andualem Gosaye’s Plea: Social Media’s Role in Crisis Aid

FEATURE NEWS: Artist’s Viral Plea Sparks Debate on Aid, Ethics, and the Limits of Social Media

A recent social media post by prominent Ethiopian artist Andualem Gosaye has ignited a firestorm of empathy, introspection, and difficult questions about crisis response, the ethics of public appeals, and the role of online communities.

In a post detailing an unspecified but severe personal hardship, Andualem laid bare a struggle that has resonated with painful familiarity for many. The raw vulnerability of the appeal, which many describe as “heart-wrenching” (hedduu garaa nama nyaata), has gone viral, drawing thousands of reactions and shares.

However, beyond the initial wave of sympathy, a more complex conversation is emerging from the comment sections and private discussions. The core of the debate centers on two poignant issues Andualem himself alluded to: the helplessness of lacking the specific skills or resources to help (gargaarsi ogummaa dhabamuun), and the profound difficulty of finding solutions for deeply entrenched problems (rakkoota akkanaa nama mudatan akkamiin akka furatan).

“This situation shows us our own limitations,” commented one social media user, echoing a sentiment felt by many. “We see the pain, we feel the urge to help, but the problem is complex. Simply sending money might not be the solution, yet doing nothing feels wrong. It puts us all in a difficult position.”

https://www.facebook.com/share/v/14SqvDrKmA7

The public nature of the plea has also sparked a meta-discussion about the mechanisms of aid. While many commend Andualem for speaking out and see crowdfunding as a valid modern tool, others express unease. They question whether social media, with its algorithms optimized for engagement over resolution, is the appropriate venue for resolving sensitive, multi-faceted personal crises. Concerns have been raised about privacy, the pressure of public scrutiny on the individual in need, and the potential for exploitation.

Amidst this, Andualem’s concluding remarks are being highlighted as a crucial guiding principle. He advocated for “seeking a fair, consensus-based solution” (murtii ariifannaa kennuu irra furmaata waloo) and emphasized that “the desire to help someone is good; thinking together is the better way” (nama gargaaru barbaaduun gaarii dha; waliif yaaduun karaa gaarii dha).

This has shifted the focus from a simple call for donations to a broader call for collective problem-solving. Followers and public figures are now asking: What structures exist—or should exist—within the artistic community and society at large to provide discreet, effective, and sustainable support for members facing extreme difficulties? How can goodwill be channeled into intelligent, respectful assistance?

The incident has become a mirror, reflecting a society grappling with how to care for its own in the digital age. It underscores the gap between immediate viral empathy and the slower, more complicated work of constructing lasting support networks. Andualem Gosaye’s personal struggle has, perhaps unintentionally, launched a public audit of communal responsibility, pushing a conversation about moving from reactive sympathy to proactive, thoughtful solidarity.

As the discussion continues, one thing is clear: the artist’s post has done more than share a hardship. It has issued a challenge to his audience and his community to evolve in how they respond when one of their own is in crisis. The path forward, as he suggested, lies not in a single transaction, but in waliif yaaduu—thinking together.

Ilfinesh Qannoo: The Artist of Resistance and Liberation

Feature Commentary: Beyond the “Cichoominaa” – The Unbreakable Symphony of Ilfinesh Qannoo

There is a word in Oromiffa that falls painfully short in describing the life of artist Ilfinesh Qannoo: cichoominaa. It translates roughly to “perseverance” or “steadfastness,” but like a thimble trying to hold an ocean, it cannot contain the vast, roaring symphony of her existence. To speak of Ilfinesh Qannoo is not to speak of merely enduring. It is to speak of a life as a deliberate, unbroken act of revolutionary art, where every strand of hair, every whispered verse, and every labored breath is a note in the grand composition of the Oromo struggle.

The call from the global Oromo community is correct and profound: she must be honored not with a single, simplistic label, but with a full-throated acknowledgment of her multi-dimensional defiance. Her life is a triptych of resistance, each panel inseparable from the others.

The First Panel: The Body as Battleground and Banner. “From the hair on her head shaved by prison guards to the fields of struggle where she stood with the WBO…” This is not merely a chronological note; it is a map of sacred scars. The shaved head was an attempt by oppressors to strip her of dignity, to reduce her to anonymity. Yet, this very act transformed her body into a public testament to state brutality. She wore that violation not as a mark of shame, but as a badge of a battle endured. Her physical presence, later frail yet carried to podiums, became a living flag—a testament that the spirit they tried to break only grew more visible, more potent.

The Second Panel: The Art as Weapon and Compass. Ilfinesh Qannoo was not an artist who occasionally addressed politics. She was a freedom fighter whose medium was verse and song. Her art was never decorative; it was directional. She took the ancient proverbs of the Oromo, like “Ilkaan socho’e buqqa’uun isaa hin oolamu” (A seed that moves does not rot), and charged them with urgent, contemporary meaning. She didn’t just write poetry; she crafted mantras for the movement, spiritual fuel for the weary, and ideological compasses for the young. Her voice, whether thundering from a stage or trembling from a frail body, did not entertain—it awakened and oriented.

The Third Panel: The Bridge Between Fronts. Her legacy dismantles artificial barriers. She stood with the Oromo Liberation Army (WBO) in spirit and solidarity, strengthening their resolve, while also being the soulful voice that reached diaspora halls, university students, and international audiences. She connected the armed vanguard to the cultural heartland, proving that the struggle is fought with both the gun and the weeduu (hymn), in both the forest and the concert hall. She was the human synapse between the political and the poetic, the military and the moral.

To call this cichoominaa is to call a hurricane a breeze. Hers is a story of alchemical resistance. She transformed personal suffering into collective strength. She translated historical oppression into timeless art. She converted the malice of her jailers into an unquenchable love for her people.

The Oromo community worldwide is right to insist on a fuller recognition. Honoring Ilfinesh Qannoo requires a vocabulary of reverence fit for a prophet-artist of liberation. She is the embodiment of Safuu (moral balance) under fire, the living Weeduu of resistance, the unyielding Odaa (sacred sycamore tree) providing shade and shelter for the movement’s spirit.

Her life proclaims that true revolution is not just a political project but an artistic and spiritual one. To honor her is to understand that the fight for bilisummaa (freedom) must also be a fight to preserve and elevate the culture, the language, and the artistic soul that she so fiercely represented. The seed she planted, through her art and her agony, is in perpetual motion. It will not rot. And for that, our gratitude must be as deep, as complex, and as enduring as her monumental life.

The Untold Heroes of Qeerroo: Jaal Abdii and Jaal Gaashuu

Feature Commentary: The Architects of Awakening – Recovering the Forgotten Genesis of Qeerroo

In the grand, often simplified narrative of the Oromo struggle, certain chapters risk fading into the footnotes of history. We speak in broad strokes: “The Qeerroo movement,” “The 2014-2018 protests,” “The youth uprising.” But movements are not spontaneous eruptions; they are meticulously seeded, nurtured, and ignited by individuals whose names deserve to be more than whispers in the wind. The story of Jaal Abdii Raggaasaa and Jaal Gaashuu Lammeessaa is one such pivotal, yet under-sung, genesis story.

The year was 2010. As the embers of the Arab Spring began to glow in Tunisia, a parallel spark was being carefully struck in the heart of Oromia. The narrative, often repeated, is that the Qeerroo Bilisummaa Oromoo (QBO) formally announced itself on April 15, 2011. But what happened in the crucible of 2010? This is where our architects enter.

Jaal Gaashuu Lammeessaa, then a key organizational figure, performed a crucial act of political translation. He looked at the revolts cascading across North Africa—Tunisia, Egypt, Libya—and posed a radical, mobilizing question to Oromo students in universities and secondary schools: “If this can happen there, why not in Oromia?” This was not mere rhetoric; it was a strategic incitement, a deliberate framing of possibility. He channeled a global moment of youth defiance into a specific, localized call to action, providing the intellectual and motivational catalyst for a generation to organize.

But a spark needs structure to become a sustained fire. This is where the senior vanguard, Jaal Abdii Raggaasaa of the Oromo Liberation Army (WBO), provided the essential scaffolding. The formal launch of the QBO on April 15, 2011, was not a rogue student act. Testimony confirms it was discussed, planned, and ratified in conjunction with Jaal Abdii Raggaasaa. This was a strategic, top-down and bottom-up alliance. The WBO, the seasoned armed wing, provided political sanction, strategic direction, and a sense of historic continuity, blessing the nascent youth movement as a legitimate front in the broader struggle.

This partnership reveals the true, hybrid nature of the movement’s birth. It dismantles the simplistic binary of “armed struggle” versus “civil protest.” Instead, it shows a calculated synergy: the WBO offering veteran legitimacy and strategic depth, and the Qeerroo injecting massive, youthful energy, digital savvy, and a broad-based civil resistance front. As noted, Jaal Abdii Raggaasaa’s enduring vision was to “integrate the Qeerroo movement and the WBO,” seeing them not as separate entities but as interlocking forces of the same liberation engine.

Yet, herein lies the poignant thrust of this recovered history: “We must acknowledge their contribution while they are still with us, not only when they are gone.” In the rush of events and the elevation of newer faces, the foundational work of such architects can be obscured. The commentary is a corrective—a call for historical accountability and gratitude within the community itself. It insists that every member, from the highest leader to the grassroots organizer, played a part, but we must be diligent in naming those who laid specific, catalytic cornerstones.

The story of Abdii Raggaasaa and Gaashuu Lammeessaa is more than a tribute; it is a lesson in movement-building. It teaches that revolutions are born at the intersection of inspiration (Gaashuu’s translational mobilizing) and institutional sanction (Abdii’s strategic integration). It reminds us that before the hashtags and the mass marches, there were quiet meetings, risky conversations, and deliberate plans.

To remember them is to understand that the “Qeerroo spirit” was not an accident of history but a deliberate construction. It is to honor the blueprint alongside the building. As the closing refrain, “Oromiyaan Biyya!” echoes, it does so with the recognition that the path to that homeland was charted by both the soldier in the field and the strategist in the shadows, by the veteran’s resolve and the organizer’s spark. Their combined legacy is the unbreakable chain that links the struggle’s past to its restless, enduring present.

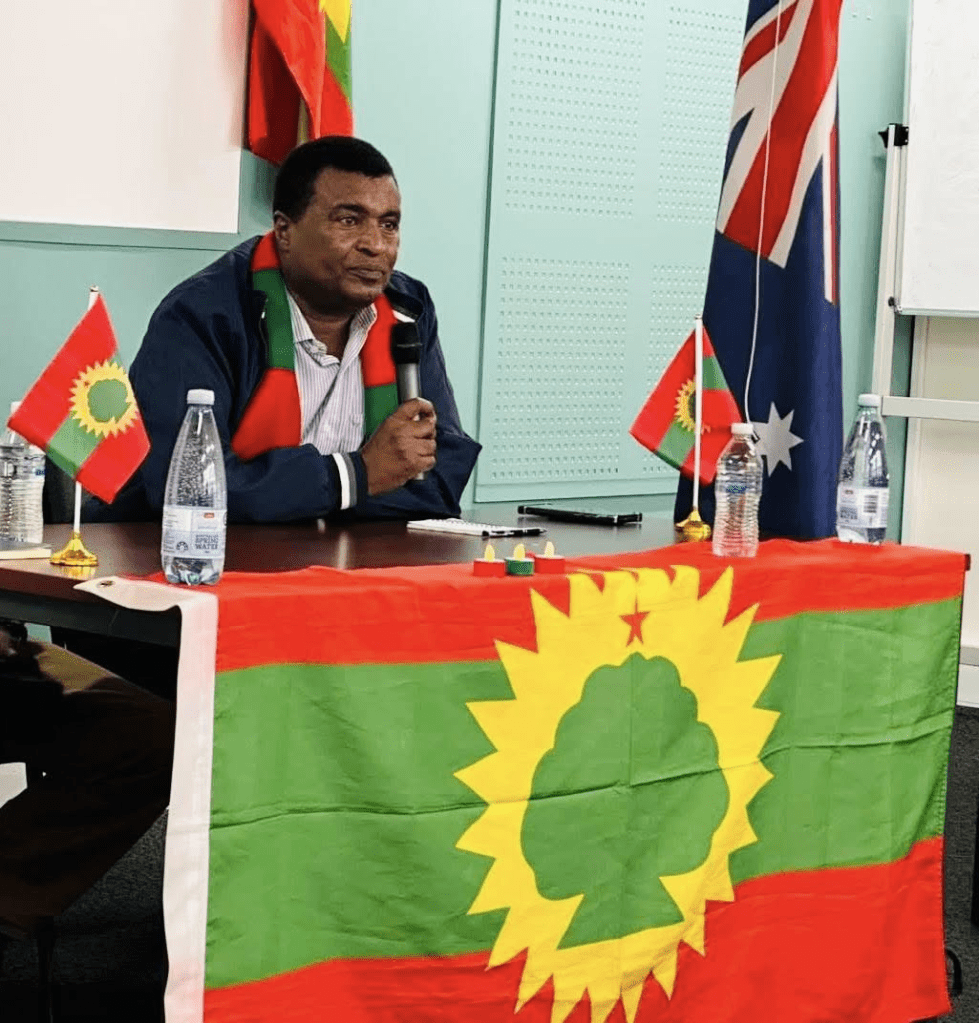

Honoring Jaal Dhugaasaa: A Symbol of Oromo Liberation

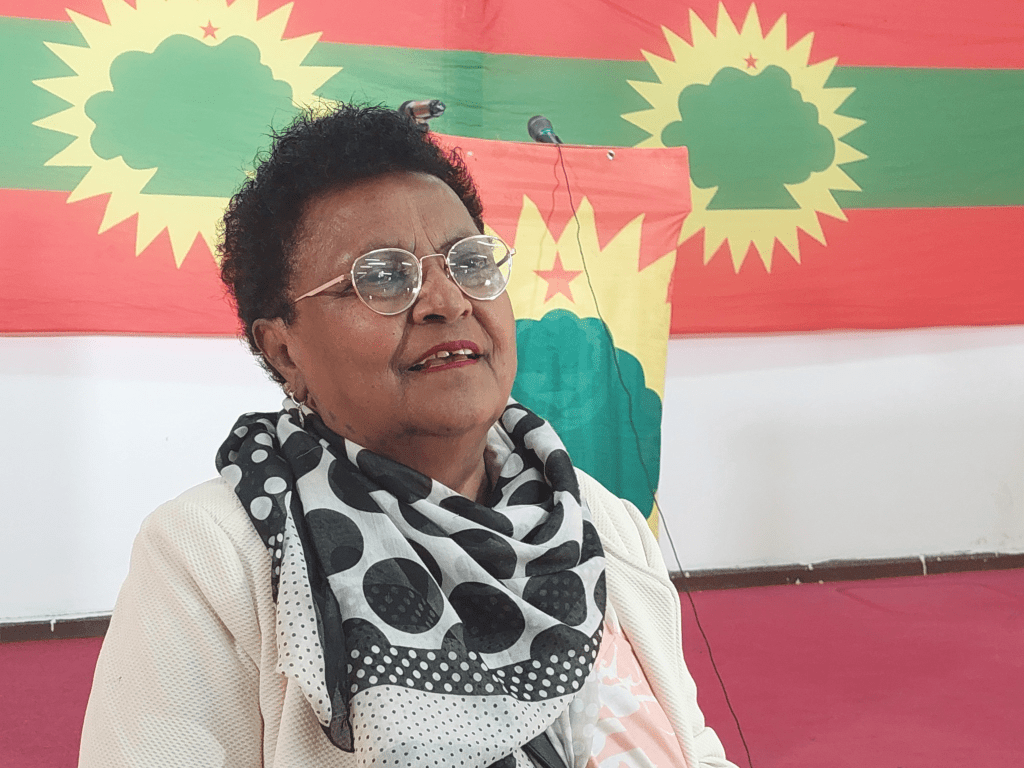

FEATURE NEWS: A Salute to the Steadfast – Honoring Veteran Oromo Freedom Fighter Jaal Dhugaasaa Bakakkoo on Oromo Liberation Army Day

In a moment that bridged generations of struggle, the presence of revered Oromo elder and veteran freedom fighter Jaal Dhugaasaa Bakakkoo became the defining symbol of this year’s Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) Day commemorations.

Attendees at the ceremony were deeply moved as the elder, a foundational figure from the very inception of the Oromo Liberation Struggle, was honored. His physical presence served as a powerful, living connection to the movement’s roots and sacrifices.

“To see with my own eyes pioneers of the Oromo struggle like Jaal Dhugaasaa, who were among the first to take up the mantle of our liberation, has filled me with immense honor,” shared one emotional attendee. “It is a profound blessing.”

The honor was made tangible with the presentation of a symbolic Alaabaa Oromoo—a ceremonial scarf of love and respect in the Oromo flag’s colors of red, green, and red. “Receiving this Alaabaa Oromoo from his hands filled me with great joy,” the recipient added. “My heartfelt thanks. You have set a supreme example for us.”

The celebration was not just a political remembrance but a heartfelt communal wish for the elder’s wellbeing. Attendees expressed their prayers for his long life, continued health, and prosperity, alongside the hope that he remains with his people for years to come. “May you live a long, healthy, and fulfilled life among your people,” was the collective sentiment, acknowledging his irreplaceable role as a living archive of the struggle’s history and values.

Jaal Dhugaasaa Bakakkoo is widely recognized as a senior figure within the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and a former executive member of its armed wing, the OLA (WBO). His life’s journey maps the evolution of the modern Oromo quest for self-determination, making his participation in contemporary commemorations a potent act of continuity.

The event underscored a central theme resonating across the diaspora this year: the unbroken chain of commitment. Honoring figures like Jaal Dhugaasaa reinforces the understanding that today’s political space and determination are built upon the sacrifices of yesterday’s pioneers. It served as both a thanksgiving to the past and a solemn passing of responsibility to ensure the “support and sustenance for the freedom struggle continues to receive continuity.”

As one participant powerfully noted, the very act of organizing such gatherings is a declaration: “By doing this, saying ‘we are here!’ is a duty that must continue.” The presence of Jaal Dhugaasaa Bakakkoo at its center was a vivid reminder of where “here” began, and why the journey must persist.

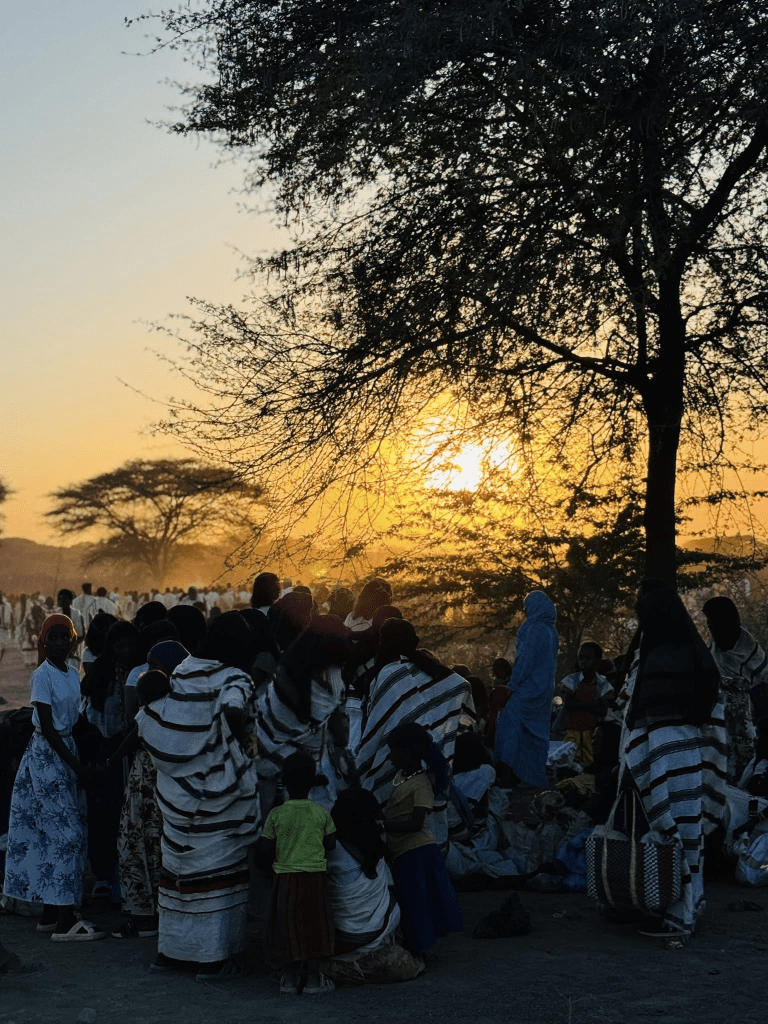

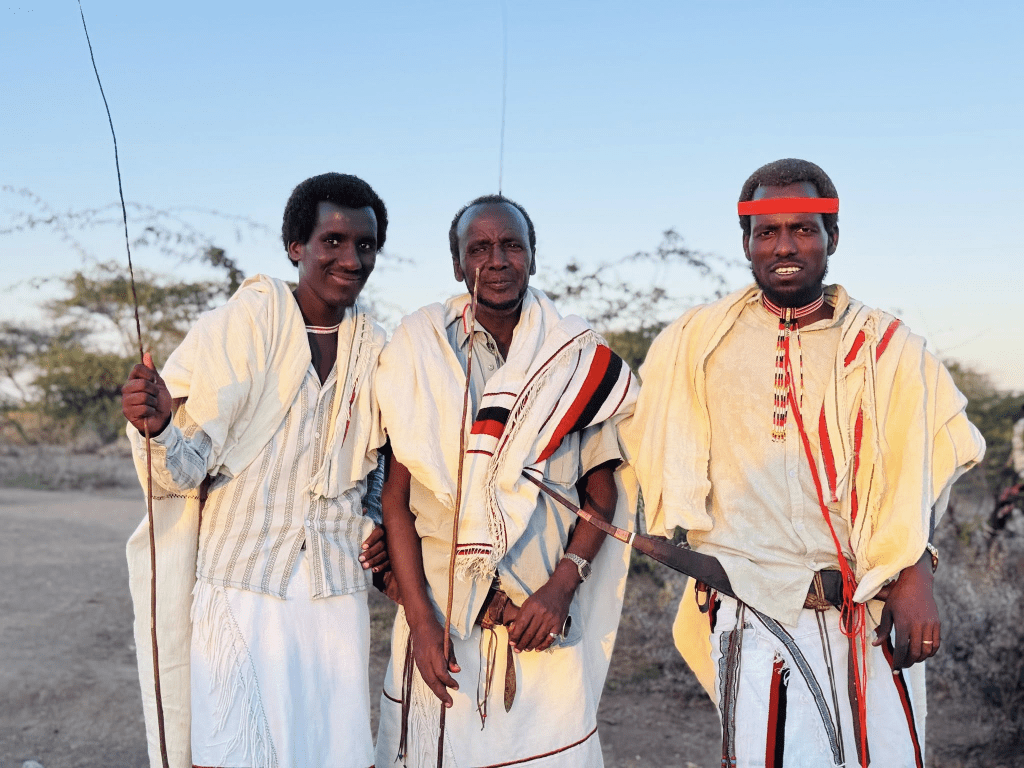

Dawn Ceremony Marks New Era for Oromo Governance

Feature News: Dawn Reclamation – Oromo Gadaa Assembly Ushers in New Era at Historic Tarree Leedii Site

FANTAALLEE, SHAWA BAHAA, OROMIA – In a powerful act of cultural restoration and communal resolve, the Oromo Gadaa system of the Karrayyuu region has formally reinstated its traditional assembly, the Sirna Goobaa, at the sacred grounds of Ardaa Jilaa, Tarree Leedii. This landmark gathering, conducted at dawn on Saturday according to sacred custom, marks not just a meeting, but the revival of an ancient democratic and spiritual heartbeat in Eastern Shawa.

The ceremony, led by Abbaa Gadaas, elders, and community representatives, began in the pre-dawn hours, adhering strictly to the profound rituals and aesthetics of Oromo tradition. Participants gathered under the ancient trees of Ardaa Jilaa, a site long held as a seat of ancestral wisdom and collective decision-making, to reignite the principles of the Sirna Goobaa—the assembly of law, justice, and social order.

“This is not a symbolic gesture; it is a homecoming,” declared one senior elder, his voice echoing in the crisp morning air. “We are reclaiming our space, our process, and our responsibility to govern ourselves according to the laws of our forefathers and the balance of nature. The Goobaa is where our society heals, deliberates, and progresses.”

The choice of location and time is deeply significant. Tarree Leedii is historically a cornerstone of socio-political life for the Karrayyuu. By convening at dawn (ganamaa), the assembly honors the Oromo cosmological view that links the freshness of the morning with clarity, purity, and the blessing of Waaqaa (the Supreme Creator). The meticulous observance of rituals involving sacred items, chants (weeduu), and the pouring of libations underscores a commitment to authenticity and spiritual sanction.

Community members, young and old, observed in reverent silence as the protocols unfolded. For many youth, it was a first-time witnessing of the full, unbroken ceremony. “To see our governance system in action, here on this land, is transformative,” said a young university student in attendance. “It connects the history we read about directly to our future. It shows our systems are alive.”

The reinstatement of the Sirna Goobaa at Ardaa Jilaa sends a resonant message beyond the borders of Fantuallee District. It represents a grassroots-driven renaissance of indigenous Oromo governance, asserting its relevance and authority in contemporary community life. It serves as a forum to address local disputes, environmental concerns, and social cohesion through the framework of Gadaa principles—Mooraa (council), Raqaa (law), and Seera (covenant).

Analysts view this move as part of a broader movement across Oromia where communities are actively revitalizing Gadaa and Waaqeffannaa institutions as pillars of cultural identity and self-determination. The successful convening at Tarree Leedii demonstrates local agency and the enduring power of these systems to mobilize and inspire.

As the sun rose over the assembly, illuminating the faces of the gathered, the event concluded with a collective affirmation for peace, justice, and unity. The revival of the Sirna Goobaa at this historic site is a dawn in every sense—a new beginning for community-led governance, a reconnection with ancestral wisdom, and a bold statement that the Gadaa of the Karrayyuu is once again in session, ready to guide its people forward.

Honoring Oromo Warriors: Cairo’s Annual OLA Day

In Cairo, a Distant Diaspora Keeps the Flame Alive: Commemorating the Oromo Liberation Struggle

CAIRO – In a gathering marked by solemn reflection and resilient spirit, the Oromo community in Cairo recently commemorated Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) Day on April 1, 2026. The event was more than a calendar observance; it was a powerful act of collective memory, a reaffirmation of identity, and a declaration of unwavering commitment to a cause that spans decades and continents.

The atmosphere was charged with the weight of history. As noted by Mr. Nasralla Abdu, Chairman of the Association, the day serves a dual purpose: to honor the souls of fallen freedom fighters and to fortify the resolve of those who continue the struggle. This is not mere ritual; it is the lifeblood of a diaspora movement, a vital mechanism to ensure that distance does not dilute purpose nor time erode sacrifice.

The historical anchor of the commemoration, as recounted, is crucial. The reference to the OLA’s reconstitution in 1980, following the severe challenges of the late 1970s, transforms April 1st from a simple date into a symbol of regeneration and stubborn endurance. It marks a moment when the struggle, against formidable odds, chose to persist. Celebrating this anniversary yearly, as the chairman explained, is to ritually reaffirm that same choice to persist, generation after generation.

The testimonies from attendees cut to the heart of the matter. For them, this was an “anniversary of covenant”—a renewal of the sacred promise to the struggle—and a moment of remembrance for those who paid the “ultimate price.” This language transcends politics; it enters the realm of collective oath and sacred duty. Furthermore, their powerful statement linking the ongoing sacrifice of Oromo people inside the homeland—for their identity, culture, history, and land—to the diaspora’s obligation to “stand in solidarity and fight for our people’s rights” creates a potent bridge. It connects the internal resistance with external advocacy, framing a unified struggle on two fronts.

This event in Cairo is a microcosm of a global phenomenon. It demonstrates how diasporas function as custodians of history and amplifiers of voice when direct expression at home is constrained. The careful observance in Egypt underscores that the Oromo quest for recognition, justice, and self-determination is not confined by geography. It is nurtured in community halls abroad as much as it is in the hearts of people within Oromia.

Ultimately, the commemoration was a tapestry woven with threads of grief, pride, and ironclad resolution. It acknowledged a painful past of loss and “severe circumstances,” celebrated the resilience that emerged from it, and boldly projected that spirit into an uncertain future. As long as such gatherings occur—where names are remembered, covenants renewed, and solidarity declared—the narrative of the Oromo struggle remains alive, authored not just by fighters on the ground but by communities in exile holding vigil for the dawn they believe must come.

Celebrating Oromo New Year 6420: A Cultural Legacy

Feature News: Celebrating Heritage and Harmony – Waaqeffannaa Faithful Usher in Oromo New Year 6420 at Walisoo Liiban Temple

WALISOO LIIBAN, OROMIA – In a profound celebration of cultural rebirth and spiritual unity, the Waaqeffannaa faithful gathered at the sacred Galma Amantaa (House of Worship) here on Thursday to solemnly and joyfully observe the Oromo New Year, Birboo, marking the dawn of the year 6420.

The ceremony was far more than a ritual; it was a powerful reaffirmation of an ancient identity, a prayer for peace, and a community’s declaration of continuity. Under the sacred Ficus tree (Odaa) that stands as a central pillar of the Galma, elders, families, and youth came together in a vibrant display of thanksgiving (Galata) to Waaqaa (the Supreme Creator) and reverence for nature and ancestry.

The air was thick with the fragrance of burning incense (qumbii) and the sound of traditional hymns (weeduu) as the Qalluu (spiritual leader) guided the congregation through prayers for blessing, prosperity, and, above all, peace for the coming year. The central message of the celebration, as echoed by the organizers, was a heartfelt benediction for the entire Oromo nation: “May this New Year bring you peace, love, and unity!” (Barri kun kan nagaa, jaalalaafi tokkummaa isiniif haa ta’u!).

This public and dignified observance of Birboo carries deep significance in the contemporary context of Oromia. As Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group navigates complex social and political landscapes, the celebration at Walisoo Liiban served as a potent symbol of cultural resilience.

“Observing Birboo at our Galma is not just about marking a calendar,” explained an elder attending the ceremony. “It is about remembering who we are. It is about connecting our past to our future, grounding ourselves in the values of balance, respect for all creation, and community that Waaqeffannaa teaches. In praying for peace, we are actively willing it into being for our people.”

The sight of children learning the rituals and youths actively participating underscored a vital theme: the intergenerational transmission of indigenous knowledge and spirituality. The celebration was a living classroom, ensuring that the philosophy of Safuu (moral and ethical order) and the connection to the Oromo calendar, based on sophisticated astronomical observation, are not relegated to history books but remain a vibrant part of community life.

The event concluded with a communal meal, sharing of blessings, and a collective sense of renewal. As the sun set on the first day of 6420, the message from the Galma Amantaa at Walisoo Liiban was clear and resonant. It was a declaration that the Oromo spirit, guided by its ancient covenant with Waaqaa and nature, remains unbroken, steadfastly hoping for and working towards a year—and a future—defined by nagaa (peace), jaalala (love), and tokkummaa (unity).

Resilience and Celebration: Oromo New Year Events Worldwide

Feature Commentary: The Unbroken Circle — How Oromo New Year Gatherings Forged a Global Covenant

As the world celebrated the turning of another calendar year, scattered communities across the globe engaged in a different kind of reckoning. From the quiet halls of Victoria, Canada, to the solitary open office in Gullalle, Oromia, and across the digital squares of a global Zoom call, the Oromo people marked the dawn of 2026 not with fleeting resolutions, but with a profound, collective covenant.

What emerged from these simultaneous gatherings—Amajjii (Oromo New Year) fused with the commemoration of the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA)—was not merely a series of cultural events. It was the clear, unified heartbeat of a movement at a critical inflection point, revealing a sophisticated national narrative being woven across continents.

The Dual Flame: Culture and Resistance

The first striking feature is the intentional fusion of the sacred and the strategic. This is no coincidence. The Eebba (invocation) of elders in Minneapolis, the shared meals in Victoria, and the celebration of Ayyaana Amajjii online are acts of cultural sustenance. They root a people in an identity that predates the current conflict. But this cultural flame is deliberately kept in the same hearth as the martial memory of the OLA. The message is unambiguous: to be Oromo is to cherish their heritage and to acknowledge the armed struggle undertaken in its defense. This duality—the cultural citizen and the resistance fighter—forms the inseparable core of the modern Oromo political identity.

From Vigil to Vanguard: The Diaspora’s Vital Role

The events in Victoria, Toronto, Minneapolis, and Edmonton powerfully redefine the role of a diaspora. This is not a community looking wistfully homeward. It is an active, organized, and indispensable limb of the body politic. When an elder in Victoria prays, “God bless our sons who sacrificed for us,” the grief is intimate and immediate. When the Edmonton chapter is honored for ensuring the “continuity” of support, it is framed as a duty, a logistical and moral lifeline.

The diaspora’s gatherings are described as declarations: “ni jirra!” — “we are here!” This presence is more than symbolic; it is the foundation for institutional strength (jabeenya jaarmiyaa), a theme hammered home in Toronto and Edmonton. In the movement’s calculus, a robust community hall abroad is as strategically vital as a forest clearing in Oromia.

The Strategic Pivot: From Resistance to Responsibility

The most significant revelation comes from the heart of the struggle itself—the Gullalle office. The address by Jaal Jabeessaa Gabbisaa there was not just a speech; it was a strategic state-of-the-union. His declaration that the OLF is transitioning from “resistance” to “elections” is a monumental shift. It signals an evolution from a movement seeking to challenge a state to one preparing to administer one.

This pivot reframes the entire struggle. The goal is no longer just recognition or even victory in a conflict, but the establishment of a democratic standard “for the world.” It is an audacious claim that immediately raises the stakes, transforming the narrative from one of victimhood to one of future governance. The admission of challenges in campaigning in certain regions underscores this new, sober, political realism.

The Unbroken Chain: Seed, Sphinx, and Succession

Amidst this strategic planning, the gatherings were anchored by powerful, human symbols of continuity. The frail but fiery activist Ilfinesh Qannoo, carried to the Gullalle stage, became the living soul of the struggle. Her proverb, “Ilkaan socho’e buqqa’uun isaa hin oolamu” (A seed that moves does not rot), provided the perfect metaphor. The Oromo movement, she argued, is that moving seed—its perpetual motion, its constant struggle, is what prevents its dream from decay.

This connects directly to the intergenerational charge that echoed in every location, from the global Zoom call to the local chapter halls. The youth are not an audience; they are, as Dr. Daggafaa Abdiisaa stated, the “beloved children of the fallen heroes” upon whom the “duty” now rests. The movement is consciously passing the torch, framing the next generation as the rightful heirs and executors of a will written in sacrifice.

Conclusion: The Virtual Hearth and the Perpetual Motion

Together, these scattered celebrations formed a single, coherent Chaffe—a traditional assembly for the digital age. The virtual Zoom hearth, the solitary Gullalle office, the prayerful halls in North America—all were nodes in a network of unwavering resolve.

They balanced the sorrow of memory with the rigor of strategy. They honored sacrifices not with passive remembrance, but with a pledge to build a future where such sacrifices cease. They announced a movement in motion, guided by the wisdom of elders, fueled by diaspora resolve, executed by a preparing youth, and strategically pivoting toward the responsibilities of a political future.

The Oromo New Year 2026, therefore, was more than a celebration. It was a global statement of perpetual motion. The seed is moving. The covenant is renewed. And the message, from every corner of the world, is one of unbroken and determined continuity.

Oromo Diaspora’s New Year Affirmation: ‘We Are Here!’

Feature Commentary: “Ni Jirra!” – The New Year’s Covenant in Edmonton

EDMONTON, ALBERTA — In a community hall thousands of miles from the Oromian highlands, a simple, powerful declaration resonated among the gathered Oromo diaspora this past week: “Ni jirra!” “We are here!”

The occasion was the celebration of the Oromo New Year, Amajjii 1, 2026, and World Brotherhood Day (WBO), organized by the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) chapter in Edmonton. But this was far more than a cultural festival. It was a strategic affirmation, a renewal of vows, and a conscious act of political endurance in the long winter of exile.

The ceremony’s significance was amplified by the distinguished presence of Jaal Dhugaasaa Bakakkoo, a senior OLF leader and a foundational figure in the WBO movement. His attendance was not merely ceremonial; it was a symbolic bridging of generations and geographies. It connected the grassroots organizational work in the diaspora directly to the historical leadership of the struggle, reminding attendees that their gatherings in Edmonton are not isolated events, but nodes in a global network of resistance.

The core of the event, however, transcended any single individual. As the commentary notes, the celebration focused intensely on “jabeenya jaarmiyaa”—the strength of the institution. This is a critical, mature evolution in diaspora political consciousness. The discussions and shared reflections (yaada ijaaraa waliif qooduu) were not just about grievances or nostalgia, but about organizational resilience, strategic continuity, and the mechanisms required to sustain a liberation movement across decades and continents.

The meticulous preparation of the program itself was framed as a direct, tangible contribution to the struggle. Organizers were thanked explicitly for ensuring that “deeggarsii fi tumsi qabsoo bilisummaa akka itti fufiinsa argatu”—that “support and sustenance for the freedom struggle continues to receive continuity.” Every detail, from the logistics to the speeches, was thus imbued with political purpose. It transformed community work from social activity into a vital supply line for a distant war of liberation.

This context makes the attendees’ declaration—“Qophii akkanaa qopheessuun ‘ni jirra!’ jechuun hojii boonsaa fi itti fufuu qabuu dha”—so profoundly meaningful. They stated: “By organizing such programs, saying ‘we are here!’ is a duty and a task that must continue.”

Here, “Ni jirra!” operates on three levels:

- Existential: We, as a people and a national project, persist. We have not been erased.

- Geopolitical: We are present and active in this Canadian city, maintaining our identity and mission.

- Institutional: The OLF, as the vehicle of our aspirations, is alive, functioning, and organizing here.

In the vastness of the Canadian prairie, this declaration is a defiant act of presence. It counters the forces of assimilation, the fatigue of a long struggle, and the sheer physical distance from the homeland. The Edmonton celebration demonstrated that for the Oromo diaspora, cultural preservation and political mobilization are inseparable. Celebrating Amajjii is an act of memory; organizing it under the OLF banner is an act of future-making.

The message from Edmonton is clear: The new year is not just a change in calendar, but a renewal of contract. The diaspora’s role is not passive waiting, but active institutional maintenance. Their prayer is not just for a good year, but for a stronger organization. Their declaration, “We are here,” is the essential, unwavering foundation upon which the dream of “being there”—in a free Oromia—ultimately depends.