Author Archives: advocacy4oromia

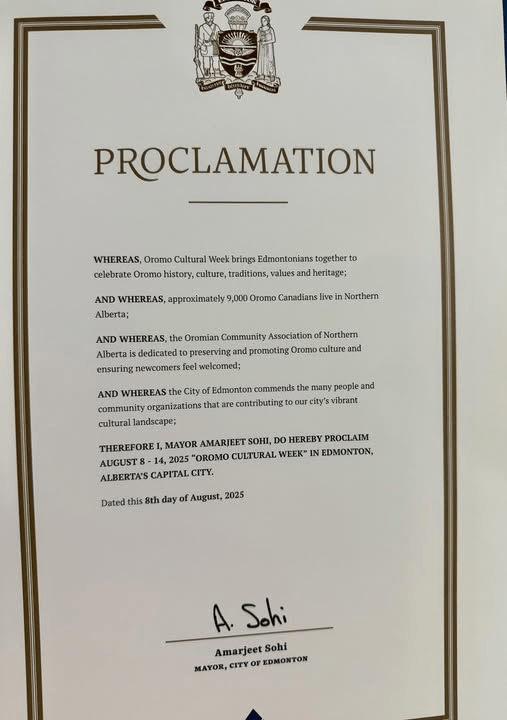

Oromo Cultural Week 2025: Celebrate Heritage in Edmonton

Oromo Cultural Week in Edmonton (August 8–14, 2025)

Celebrating Oromo Heritage, Unity & Resilience

📍 Location: Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

📅 Dates: August 8–14, 2025

🎉 Highlights: Traditional music, dance, art, history forums, and community feasts.

Expected Events & Activities

(Based on past Oromo cultural weeks in Canada; official schedule TBA)

1. Opening Ceremony (Aug 8)

- Speeches by Oromo elders & community leaders.

- Flag-raising (Oromo & Canadian flags).

- Traditional blessings (Waaqeffannaa prayers).

2. Cultural Showcase (Aug 9–10)

- Oromo Dance & Music: Dhaanto, Geerarsa, Shaggooyyee performances.

- Fashion Show: Traditional Horo Guduru attire and modern Oromo designs.

- Art Exhibition: Oromo paintings, crafts, and photography.

3. History & Identity Forum (Aug 11)

- Panel Discussions: Oromo history, Gadaa system, and diaspora experiences.

- Documentary Screenings: Films like “Oromo: The Forgotten People”.

4. Sports & Youth Day (Aug 12)

- Soccer Tournament: Oromo teams from across Canada.

- Poetry & Spoken Word: Young Oromo artists sharing their voices.

5. Community Feast (Aug 13)

- Oromo Cuisine: Injera, Waaddii (mariqaa), Buna Qalaa (coffee ceremony).

- Storytelling: Elders sharing oral histories.

6. Closing Celebration (Aug 14)

- Grand Concert: Oromo artists (local & international).

- Award Ceremony: Honoring community contributors.

How to Participate

✅ Attend: Open to all—Oromo community members & allies.

✅ Volunteer: Help with organizing (contact Oromo Canadian Community Association).

✅ Perform/Exhibit: Showcase your talent (music, art, poetry).

Organizers & Contacts

🔹 Oromo Canadian Community Association (OCCA)

🔹 Edmonton Oromo Youth Group

📩 Check Facebook/Eventbrite for official updates closer to the date.

Why This Matters

This week is a powerful way to:

- Preserve Oromo culture in the diaspora.

- Educate others about Oromo identity.

- Strengthen unity among Oromo Canadians.

“ Bilisummaa fi Walabummaa! “ (Freedom & Liberty!)

Need help finding specific details (e.g., venues, registration)? Let me know—I’m happy to dig deeper! 🌍💛

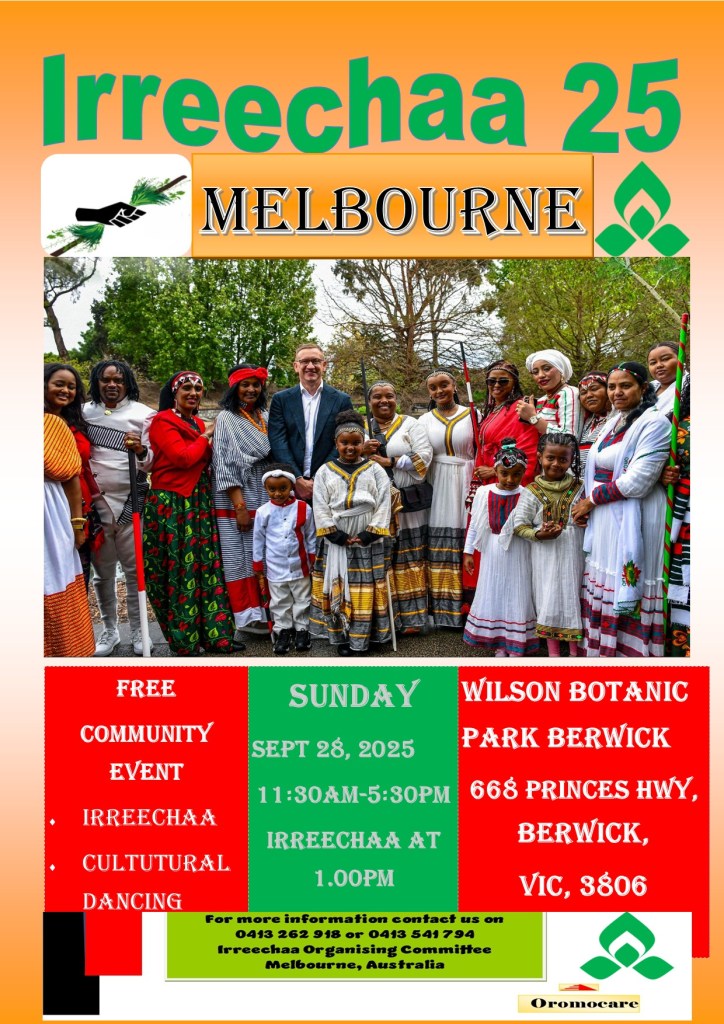

Irreechaa 25 Festival – Melbourne

Here’s a clear summary and important information for the **Irreechaa 25** event in Melbourne:

**Irreechaa 25 Festival – Melbourne**

* **Date:** Sunday, 28 September 2025

* **Time:** 11:30 AM to 5:30 PM

* **Location:** Wilson Botanic Garden

* **Address:** 668 Princes Hwy, Berwick VIC 3806

**Key Details:**

1. **Significance:** Irreechaa is the major **Oromo Thanksgiving Festival**, celebrating the end of the rainy season, blessings of the past year, and welcoming the new spring season (in the Southern Hemisphere context, it aligns with the end of winter/start of spring). This marks the **25th anniversary** of Irreechaa celebrations in Melbourne.

2. **Venue:** Wilson Botanic Garden in Berwick is a beautiful and spacious public park, well-suited for large cultural gatherings like this.

3. **What to Expect:**

* Traditional Oromo prayers, songs, and speeches.

* Cultural performances including music and dance (like the *Shaggooyyee*).

* Community gathering and socializing.

* Traditional Oromo attire is often worn.

* Food and refreshments (likely available for purchase from vendors).

* A vibrant and family-friendly atmosphere celebrating Oromo culture and heritage.

**Practical Information:**

* **Transportation:**

* **Public Transport:** Take a train to **Berwick Station** (on the Pakenham line). From the station, it’s about a 15-20 minute walk (1.3 km) to the Garden entrance. Local buses also serve the area near the highway – check the PTV app/website for routes like 828, 830, 835, or 836 stopping near the Garden.

* **Parking:** Limited free parking is available within Wilson Botanic Garden, and street parking is available on surrounding roads. **Arrive early as parking can fill up quickly for large events.**

* **What to Bring:**

* Comfortable shoes (the Garden has walking paths).

* Sun protection (hat, sunscreen) or rain gear (Melbourne weather can be changeable in September).

* A blanket or picnic rug for sitting on the grass.

* Water bottle.

* Cash might be useful for smaller vendors, though card facilities are increasingly common.

* **Accessibility:** Wilson Botanic Garden has accessible paths and facilities. Check specific event details closer to the date for any accessibility services provided by the organizers.

**For the Most Up-to-Date Information:**

It’s always wise to check official sources or community social media pages closer to the event. Look for pages associated with the **Oromo Community Association in Victoria** or similar groups.

This is a wonderful opportunity to experience the rich culture and traditions of the Oromo community in Melbourne. Enjoy the celebrations!

Conservation Ambitions: Ethiopia Plants 700 Million Trees

ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia (AP) — Ethiopia launched a national campaign on Thursday to plant 700 million trees in one day as part of an ambitious conservation initiative that aims to plant 50 billion trees by 2026.

The reforestation campaign has been a personal project of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed since 2019.

Tesfahun Gobezay, state minister for the Ethiopian Government Communication Services, told reporters before 6 a.m. local time that some 355 million seedlings had already been planted by 14.9 million Ethiopians.

It was not possible to verify the government’s figures. Ethiopia has a population of more than 120 million people.

“We kicked off this year’s one-day green Legacy planting early this morning,” Abiy said on social media platform X. “Our goal for the 7th year is 700 million seedlings. Let’s achieve it together.”

Authorities say some 40 billion tree seedlings have been planted since 2019. The target for 2025 is 7.5 billion trees.

Abiy took power in 2018 as a reformist. He won the Nobel Peace Prize for making peace with neighboring Eritrea but a war that erupted shortly afterward in the Ethiopian region of Tigray damaged his reputation as a peacemaker. He now he faces another rebellious uprising in the Amhara region.

Many public offices are closed Thursday to make time for tree planting. Thousands of public servants have been dispatched across the east African nation to help plant seedlings made available through the official bureaucracy.

At the break of dawn, many were seen planting trees in the capital Addis Ababa. At a site in Jifara Ber dozens of people were involved, including children.

Almaz Tadu, a 72-year-old grandmother, brought her grandchildren to a tree planting event she said reunites her with neighbors.

“I have come with my mother and this is my third time planting trees,” said 13-year-old student Nathenael Behailu. “I dream of seeing a green environment for my country.”

Another Addis Ababa resident, Ayanaw Asrat, said he has heeded the call for the last three years. “I came early and I have so far planted 15 seedlings. I am very happy to contribute to creating greener areas across Addis,” he said.

Abiy himself was active in Jimma, the largest city in the southwestern region of Oromia. Cabinet ministers were sent to other regions to support local officials.

Kitessa Hundera, a forest ecologist at Jimma University, told The Associated Press that a “noble” reforestation initiative was being carried out by non-experts who could not define conservation objectives regarding site selection and other technical issues.

He cited concern over mixing exotic species with indigenous ones and the apparent failure to report the survival rate of seedlings planted over the years. He also doubted it was possible to plant 700 million seedlings in one day.

“Planting 700 million seedlings in one day needs the participation of about 35 million people, each planting 20 seedlings, which is practically impossible,” he said.

Building a Sovereign Nation: The Oromo Path to Stability

By By Bantii Qixxeessaa

A common argument raised against the Oromo liberation struggle for independence is this:“Even if Oromia becomes independent, how do we know it won’t end up like South Sudan, Eritrea, or Somalia—mired in authoritarianism, internal conflict, or state collapse?”This is a sobering question. It deserves more than a dismissal. It demands reflection, honesty, and a credible roadmap.There is truth in the concern. History confirms that independence alone does not guarantee peace, freedom, or democracy. There is truth in the concern. History confirms that independence alone does not guarantee peace, freedom, or democracy. South Sudan gained independence in 2011 after a long and bloody struggle, only to descend into civil war and political dysfunction.

Eritrea fought heroically for sovereignty, only to replace foreign domination with domestic repression. Somalia collapsed into stateless chaos after the fall of its authoritarian regime. In all three cases, the post-independence vision was either unclear, co-opted, or completely abandoned.

But this is only one side of the story.

There are also powerful examples of nations that won independence and successfully built stable, democratic, and sovereign states. Timor-Leste, after decades of brutal occupation, transitioned into a pluralistic democracy with repeated peaceful elections. Namibia emerged from South African apartheid rule to become one of Africa’s most stable democracies. Slovenia, which broke away from Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, managed a peaceful transition and integrated swiftly into the European Union. Botswana – Maintained multiparty democracy and rule of law since 1966. Cape Verde – Peacefully transitioned to multiparty democracy and maintained political stability. India – Despite enormous diversity and challenges, India preserved electoral democracy since independence. These cases, and others not mentioned here, remind us that independence, when coupled with visionary leadership, institution-building, and inclusive governance, can yield not only sovereignty—but peace, democracy, and prosperity.

The point is clear: independence is not a guarantee of success, but neither is it a path to inevitable failure. The outcomes depend on preparation, political culture, and strategic execution.

So the question is not whether independence is worth pursuing, but whether we are willing to do the hard work to ensure it leads to a just and thriving Oromia. For Oromia, the lesson is not to be discouraged by the odds, but to be disciplined by them. The struggle must not end with independence, it must start with building the foundations of the state we want to live in.

Independence Alone Does Not Guarantee Peace, Freedom, or Democracy

The Oromo struggle is not merely about redrawing borders. It is about reclaiming power from an empire that has long denied the Oromo people the right to govern themselves. That goal will only be fulfilled when the new Oromia is built on justice, freedom, and democratic accountability.

The failure of other post-independence states was not that they chose sovereignty, but that they did not adequately plan what to do with it once they had it. For them Independence became an endpoint instead of a beginning. Oromia must learn from their experience.

What Went Wrong with these movement, later states? Here as some Key Lessons.

- Lack of Political Consensus: South Sudan’s liberation forces fractured along ethnic (the Dinka and the Nuer) and personal rivalries (Salva Kiir Mayardit and Riek Machar) after independence. Their unity was wartime-deep but not nation-deep.

- Weak Institutions: Eritrea’s government was centralized around a single figure, Isaias Afwerki. In the absence of independent institutions, authoritarianism became inevitable. The concentration of power in one leader, the failure to implement a democratic transition after independence, the systematic suppression of dissent, the militarization of governance, and the entrenchment of one-party rule without internal accountability made authoritarianism not just likely—but the logical outcome.

- Militarization of Politics: In both South Sudan and Eritrea, there was no planned and inclusive transition to civilian-led, democratic governance. Instead, armed movements transitioned into ruling elites without civilian oversight, perpetuating a culture of command over consent.

- Failure to Transition from Liberation to Governance: If a liberation movement is undemocratic in its internal organization and decision-making during the struggle, it is likely to reproduce those same authoritarian habits once it comes to power. In both the South Sudanese and Eritrean liberation struggles, the movements failed to democratize internally and instead carried autocratic tendencies into statehood.

- Neglect of Reconciliation and Inclusion: Neither South Sudan nor Eritrea implemented meaningful, independent truth, reconciliation, or justice commissions after achieving independence. The absence of such mechanisms played a significant role in their post-liberation crises.Somalia’s fragmentation was deepened by the exclusion of key clans and groups, undermining the legitimacy of national institutions.

- No Economic Vision: Liberation without economic development leads to frustration, elite capture, and failed expectations. neither South Sudan nor Eritrea had well-developed or realistic economic development plans when they gained independence. This absence of clear, inclusive, and sustainable economic strategies significantly contributed to post-independence frustration, elite capture, and ultimately state failure or stagnation.

How Can the Oromo Movement Avoid These pitfalls?

- Start Nation-Building Before Statehood: Nation-building must begin during the struggle—not after victory. This means cultivating democratic norms, inclusive leadership, institutional habits, and a shared civic vision now, so Oromia rises not just as a state, but as a nation rooted in justice, dignity, and self-rule.

We can begin this process by:

a. Democratizing the Movement Itself: Hold inclusive consultations across Oromo political organizations. Practice internal democracy—rotate leadership, hold free elections, and foster open debate without branding dissent as betrayal. A democratic state cannot emerge from undemocratic movements.

b. Developing a Shared Vision: Draft a People’s Charter or “Oromo Covenant” through public forums that articulates the future state’s core values (democracy, justice, equality), defines citizen rights and responsibilities, and establishes unifying symbols and narratives.

c. Building and Strengthen Oromo Institutions: Create shadow institutions like diaspora parliaments, advisory councils, and grassroots dispute-resolution platforms. Launch Oromo think tanks and development organizations to shape post-independence governance. Sustainable nations rely on institutions—not just leaders.

d. Drafting a Transitional Roadmap: Prepare a clear, inclusive plan for transferring power post-independence. Include a transitional charter, a timeline for elections, constitution-making, and institution-building. Planning now prevents chaos later. Such planning helps prevent power grabs and chaotic improvisation during a fragile transition.

e. Modeling Inclusive Leadership and Conflict Resolution: Initiate dialogues among Oromos across regions, religions, and political lines to build trust and reconciliation. Use traditional Oromo mechanisms (e.g., Gadaa) and modern legal norms to manage disputes. Promote leaders guided by integrity, not allegiance. Independence cannot bring stability without reconciliation and trust.

- Ensure Civilian Supremacy: Armed resistance must not give rise to a ruling military caste. Civilian political authority must guide Oromia’s future. If the Oromo liberation movement seeks to build a just and democratic state, it must begin now to ensure that guns return to the barracks—and governance rests with the people through ballots, not bullets. Civilian supremacy—the principle that elected or accountable civilian leadership controls the military—is essential to preventing post-independence authoritarianism. To uphold this principle, the movement must take deliberate steps during the struggle to clearly define and separate military and political roles.

- Forge a National Covenant: Develop a pre-independence social contract that binds Oromo regions, parties, and communities together in shared purpose. Forging a National Covenant is a strategic and unifying step that helps consolidate internal cohesion, articulate a collective vision, and lay the foundation for inclusive governance after independence. It transforms aspiration into agreement, agreement into accountability, and accountability into a shared destiny. The Covenant offers a moral foundation and unifying framework that can endure political transitions and guide the creation of a democratic Oromia. By ensuring all major segments of Oromo society have a stake in it, the Covenant becomes both a political backbone and a public promise. Embedded in the movement’s strategy, it serves as the compass for nation-building—before and after independence.

- Guarantee Inclusivity for All Peoples: Oromia will be home to non-Oromo minorities, and any future vision must ensure their protection and full citizenship. Guaranteeing inclusivity—especially for non-Oromo communities—is both a moral imperative and a strategic necessity for legitimacy, stability, and democratic state-building. This is not a concession; it is a declaration of confidence in a democratic future. By ensuring that all residents feel a genuine sense of belonging, the Oromo movement lays the foundation for a stronger, more unified, and enduring nation.

- Prepare a Transitional Charter and Leadership Framework: Governance must not be improvised. A clear roadmap for the first five years—outlining institutions, timelines, elections, and reforms—is essential. Preparing a Transitional Charter and Leadership Framework ensures that post-independence Oromia is not vulnerable to instability, power struggles, or elite capture. It signals maturity, foresight, and credibility—both to the Oromo people and the international community. Such a framework provides the structure, stability, and legitimacy Oromia will need during its most fragile moment: immediately after independence. States should not be improvised—they must be deliberately designed.

- Establish a Truth and Justice Commission: Addressing historical wounds through transparent, accountable processes is essential for justice and healing—not revenge. A Truth and Justice Commission (TJC) is vital for legitimacy and nation-building, especially in Oromia, where the people have endured decades of systemic violence, dispossession, and betrayal. Crucially, the groundwork for such a commission must be laid before independence to ensure swift and credible implementation afterward. Truth and justice must not wait—they must be integral to the liberation itself. By planning now, the Oromo movement demonstrates that it seeks not just power, but moral legitimacy and national healing. In doing so, it breaks the cycle of revenge and paves the way for a democratic future rooted in memory, accountability, and reconciliation.

- Develop Economic Sovereignty: Plan now for food security, youth employment, regional trade, and resource equity, so that political independence translates into real, lived freedom. Economic sovereignty is essential to ensuring that Oromia’s future is not symbolic but substantive. True sovereignty is not just a flag or a border, it is the ability to feed, employ, and empower your people. Building the foundations of a dignified life must be central to the liberation struggle. The Oromo movement must treat economic development not as a post-independence task, but as a core pillar of liberation itself.

The Cost of Caution vs. the Risk of Action

Opponents of independence argue that avoiding these risks is reason enough to remain under the Ethiopian so called federation. But Ethiopia’s own record is one of repression, fragmentation, and crisis. Remaining in the current system is not a guarantee of peace or prosperity, it is a guarantee of stagnation, dependency, and continued repression and subjugation.

The Oromo people are not doomed to repeat the mistakes of others. But they must learn from them, seriously, humbly, and strategically. The goal is not just a new flag. It is a new political culture, rooted in the principles the Oromo struggle has long proclaimed: freedom, equality, justice, and self-rule.

Independence is only the first chapter—but without it, the rest of the story cannot be written.

Opponents of Oromo independence often argue that its advocates are fixated on symbols—new flags, new borders—without a plan for what comes next. Nothing could be further from the truth. The call for independence is not about retreating into nationalism; it is about unlocking the possibility of justice, peace, democracy, and dignity—none of which have ever been guaranteed under the current imperial structure.

The reality is this: for the Oromo people, there can be no meaningful next chapter without the first one. There can be no justice without sovereignty. No peace without self-rule. No democracy without the freedom to determine our own future. Independence is not the end goal—it is the beginning of a better path. The Oromo movement must and does look beyond independence, but it also recognizes that independence is the necessary foundation on which every future reform must rest.

We are not asking for isolation. We are demanding inclusion—on our own terms, in our own voice, in our own land.

(Published as part of the “Oromia Rising: Essays on Freedom and the Future” series. Everyone is invited to contribute. Send your contributions to bantii.qixxeessaa@gmail.com.)

Oromo Indigenous Knowledge: Smart Erosion Solutions for Ethiopia

Why scientists are turning to Oromo indigenous knowledge for erosion solutions?

Scientists are increasingly turning to Oromo Indigenous Knowledge (IK) for erosion solutions, particularly in the Ethiopian highlands, due to several compelling reasons:

1. **Severity of Erosion in Oromo Lands:** The Ethiopian highlands, home to a large Oromo population, are among the world’s most erosion-prone regions. Decades of deforestation, population pressure, intensive agriculture on slopes, and climate change impacts have caused catastrophic soil loss, threatening food security, water resources, and livelihoods. Conventional approaches alone haven’t sufficed.

2. **Limitations of Conventional Solutions:**

* **Cost & Scalability:** Large-scale engineering solutions (like extensive terracing or dams) are often prohibitively expensive and difficult to implement and maintain over vast areas.

* **Top-Down Approach:** Imported technical solutions sometimes fail to consider local ecological specificity, social structures, and economic realities, leading to poor adoption or abandonment.

* **Sustainability:** Some conventional methods may rely heavily on external inputs or lack long-term ecological integration.

3. **Strengths of Oromo Indigenous Knowledge (QBS – *Qaalluu*, *Baayyee*, *Safuu*):** Oromo environmental knowledge, often guided by the philosophy of *Qaalluu* (spiritual connection/balance), *Baayyee* (diversity/abundance), and *Safuu* (moral/ecological order), offers proven, context-specific solutions:

* **Holistic Land Management:** The *QBS* system integrates crops, trees, livestock, and social structures. Practices are interconnected, supporting each other and the overall ecosystem health.

* **Time-Tested & Locally Adapted:** IK has evolved over centuries *in situ*, making it uniquely adapted to local soils, climates, topography, and biodiversity. Its persistence proves its effectiveness under local conditions.

* **Effective Specific Practices:**

* **Agroforestry & Multipurpose Trees:** Integrating native trees (e.g., *Cordia africana* – Waddeessa, *Croton macrostachyus* – Bakkanniisaa) for shade, fodder, fuel, soil improvement, and **root systems that bind soil**.

* **Mixed Cropping & Intercropping:** Planting diverse crops together (e.g., cereals with legumes or root crops) provides better ground cover year-round, reducing splash erosion and improving soil structure.

* **Contour Farming & Natural Terracing:** Planting along contours and using specific grasses/shrubs on terrace edges (*Furrii* or *Garbii*) to stabilize them effectively.

* **Crop Residue Management:** Leaving crop residues (*Eebba*) as mulch protects the soil surface from raindrop impact, reduces runoff, conserves moisture, and adds organic matter.

* **Rotational Grazing & Livestock Integration:** Controlled grazing prevents overgrazing, while manure application improves soil fertility and structure. Specific grasses (*Gorii*) are promoted for erosion control on slopes.

* **Micro-Catchments & Water Harvesting:** Traditional techniques like *Targa* (small pits) and *Doyyoo* (micro-basins) capture runoff, allowing water to infiltrate and reducing erosive flow.

* **Sacred Groves & Community Forests:** Protected areas (*Odaa*, *Gudaa*) conserve biodiversity, stabilize slopes, regulate water flow, and serve as repositories of indigenous knowledge.

* **Cost-Effectiveness & Accessibility:** IK relies primarily on locally available materials, labor, and knowledge, making it far more affordable and accessible for local communities.

* **Community Ownership & Social Capital:** IK is embedded in community structures, norms, and governance systems (like the *Gadaa* system). This fosters strong community ownership, participation, and long-term maintenance of conservation measures.

* **Sustainability & Resilience:** Oromo IK emphasizes maintaining ecological balance and diversity, leading to inherently more resilient and sustainable land management systems.

4. **The Shift Towards Participatory & Integrated Approaches:**

* **Recognition of IK Value:** Scientists increasingly acknowledge that IK offers invaluable insights and practical, sustainable solutions often overlooked by purely technical approaches.

* **Co-Production of Knowledge:** The trend is towards collaborative research where scientists work *with* Oromo communities to document, understand, scientifically validate, and refine IK practices. This respects local expertise and ensures solutions are culturally appropriate and readily adopted.

* **Hybrid Solutions:** Combining the strengths of IK (local adaptation, cost-effectiveness, social integration) with relevant scientific innovations (precise mapping, improved plant varieties, targeted engineering) creates more robust and effective erosion control strategies. For example, scientific validation of the effectiveness of specific native plants used in bund stabilization.

* **Policy Shifts:** International frameworks (like CBD, UNCCD) and national policies increasingly emphasize the importance of integrating IK into sustainable development and environmental management.

5. **Addressing Climate Change:** IK systems, developed to cope with variability, offer valuable strategies for building resilience to climate change impacts like increased rainfall intensity and droughts, which exacerbate erosion.

**Challenges in Integration:**

* **Documentation:** Much IK is oral and localized, requiring careful, respectful documentation.

* **Validation & Understanding:** Scientific research is needed to understand *why* and *how* some practices work so effectively.

* **Power Dynamics:** Ensuring equitable partnerships where communities are genuine co-researchers and benefit equitably from any outcomes or commercialization.

* **Changing Contexts:** Adapting IK to rapidly changing social, economic, and climatic conditions while preserving its core principles.

**In essence, scientists are turning to Oromo IK because it provides a treasure trove of proven, sustainable, cost-effective, and culturally grounded erosion control practices. Integrating this deep local wisdom with scientific knowledge offers the most promising pathway towards tackling the severe land degradation challenges in Oromo territories and similar regions.** It represents a move towards more holistic, participatory, and ecologically sound land management.

Harnessing Oromo Wisdom for Effective Environmental Conservation

Why scientists are turning to Oromo indigenous knowledge and wisdom for environmental protection and conservation?

Scientists are increasingly turning to Oromo indigenous knowledge and wisdom (often referred to as **Aadaa Seeraa** and embedded within systems like the **Gadaa**) for environmental protection and conservation for several compelling reasons:

1. **Proven Sustainability Practices:** The Oromo people have inhabited and managed diverse ecosystems in the Horn of Africa (primarily Ethiopia and Kenya) for centuries, even millennia. Their traditional practices in agriculture (e.g., crop rotation, intercropping), pastoralism (e.g., controlled grazing, herd diversification), forestry (e.g., sacred groves – *Deddeettii*), and water management have demonstrably sustained these environments long before modern conservation science existed. Scientists recognize these as time-tested models of living *with* nature rather than dominating it.

2. **Deep Ecological Knowledge and Biodiversity Conservation:**

* **Species Knowledge:** Oromo knowledge includes intricate understanding of local flora and fauna – their uses (medicinal, nutritional, material), life cycles, ecological roles, and interactions. This is invaluable for identifying species, understanding ecosystem health, and prioritizing conservation efforts.

* **Habitat Management:** Practices like protecting sacred forests (*Deddeettii* or *Jaarsummaa*), wetlands, and water sources (*Hora*) act as de facto biodiversity reserves and ecological corridors. These areas are often off-limits to exploitation, preserving critical habitats and genetic resources.

* **Sustainable Resource Harvesting:** Rules govern the harvesting of wild plants, honey, and other resources, ensuring regeneration and preventing over-exploitation.

3. **Resilience and Adaptation Strategies:** Indigenous Oromo knowledge contains sophisticated strategies for coping with environmental variability, drought, and climate extremes – challenges that are intensifying with climate change. This includes:

* **Drought-Resistant Crops & Varieties:** Knowledge of locally adapted, resilient crop varieties.

* **Water Conservation Techniques:** Traditional methods for locating, conserving, and sharing water resources.

* **Early Warning Systems:** Ecological indicators used to predict weather patterns, droughts, or pest outbreaks (e.g., behavior of certain birds, flowering patterns of specific trees).

* **Livestock Management:** Strategies for moving herds during drought, diversifying livestock types for risk spreading, and utilizing diverse forage resources.

4. **Effective Governance and Social Sanctions (Gadaa System):** The Gadaa system, a complex indigenous democratic socio-political system, incorporates strong environmental governance principles:

* **Codified Laws (Seera Waaqaa – Laws of Waaqa/God):** Explicit environmental laws prohibiting pollution of water, wanton destruction of trees, killing of certain animals, and regulating land use and resource access.

* **Community Enforcement:** Environmental stewardship is a communal responsibility. Violations of environmental laws carry significant social and spiritual sanctions, ensuring compliance more effectively than external enforcement in many contexts.

* **Intergenerational Equity:** The Gadaa’s cyclical nature inherently promotes long-term thinking and responsibility towards future generations (“*Safuu*” – moral and ethical responsibility).

5. **Holistic and Spiritual Worldview (Waaqeffannaa):** The Oromo worldview, often centered around Waaqeffannaa (belief in Waaqa, the supreme creator), sees humans as an integral part of nature, not separate or superior.

* **Sacredness of Nature:** Mountains, rivers, lakes, forests, and specific trees are often considered sacred abodes of spirits or manifestations of Waaqa, commanding deep respect and protection.

* **Concept of Safuu:** This ethical concept emphasizes balance, respect, and responsibility towards all creation – humans, animals, plants, and the land itself. Exploitation violates *Safuu*.

* **Rituals and Taboos:** Many rituals reinforce the connection to nature, and taboos (*Qaayyoo*) often protect specific species or areas at critical times (e.g., breeding seasons).

6. **Addressing Limitations of Top-Down, Western Science:**

* **Local Context:** Western scientific approaches can be generic and fail to account for specific local ecological, social, and cultural contexts. Oromo knowledge is hyper-local and deeply contextual.

* **Community Buy-in:** Conservation projects imposed from outside often fail due to lack of local understanding and ownership. Integrating indigenous knowledge fosters community participation, legitimacy, and long-term sustainability of conservation efforts.

* **Cost-Effectiveness:** Leveraging existing local knowledge and governance structures can be more practical and cost-effective than establishing entirely new, externally managed systems.

7. **Ethical Shift and Recognition of Rights:** There’s a growing ethical recognition within science and global conservation (e.g., IPBES, CBD) that:

* Indigenous peoples are the original stewards of vast biodiversity-rich areas.

* Their knowledge systems are valid, sophisticated, and hold critical solutions.

* Marginalizing or ignoring this knowledge is not only unjust but also counterproductive to conservation goals. Respecting and integrating it is a matter of rights and justice.

8. **Practical Applications:** Scientists are collaborating with Oromo communities to:

* Restore degraded lands using traditional techniques.

* Design community-based conservation areas incorporating sacred sites.

* Develop climate adaptation plans based on indigenous forecasting and resilient practices.

* Document and preserve ecological knowledge before it is lost.

**In essence, scientists recognize that Oromo indigenous knowledge offers:**

* **Time-tested, sustainable practices** refined over generations.

* **Deep, place-based ecological understanding** crucial for effective management.

* **Robust governance and ethical frameworks** that ensure compliance and long-term thinking.

* **Critical strategies for resilience** in the face of climate change.

* **A pathway to more effective, equitable, and culturally relevant conservation** that engages local communities as partners.

This shift represents a move towards more inclusive, holistic, and effective approaches to tackling the global environmental crisis by learning from those who have successfully managed their environments for centuries. The UNESCO recognition of the Gadaa system as Intangible Cultural Heritage further underscores its global significance, including its environmental governance aspects.

የሀዘን መግለጫ-ከኦሮሞ ነጻነት ግንባር (ኦነግ) የአውስትራሊያ ቅርንጫፍ

ኦሮሞ ነጻነት ግንባር (ኦነግ) እና የአውስትራሊያ ቅርንጫፉ የታላቋ ኦሮሞ ታጋይ፣ የባህል ተከታይ፣ የቋንቋ አስተማሪ፣ የታሪክ አስተናጋጅ እና የትግል አመራር ጃል ኩምሳ ቡራዩን (1969-2025) በፐርዝ፣ ምዕራብ አውስትራሊያ ህይወት ካለፈ በኋላ በጥልቅ ሀዘን እና በከፍተኛ አድናቆት እያከበርን የሀዘን መግለጫችንን እናቀርባለን።

ጃል ኩምሳ ለኦሮሞ ህዝብ ነጻነት፣ ለባህሉ ብልጫ፣ ለቋንቋው ትርጉም እና ለታሪኩ ትክክለኛ ማስታወሻ የዘለቀ አስተዋፅኦ አበርክቷል። በተለይም በኦነግ የባህር ማዶ መዋቅር ስር የአውስትራሊያን ቅርንጫፍ በማቋቋም ረገድ የከፈለው አስተዋፅኦ የማይረሳ ነው። በትግሉ ዘመቻዎች፣ በማህበራዊ እንቅስቃሴዎች እና በባህላዊ ስራዎች ላይ ያለው አስተዋፅኦ ለዘለቄታዊ ትውልድ መምሪያ እና መነሻ ነው።

ኦነግ እና የአውስትራሊያ መዋቅሩ ጃል ኩምሳን ለትግሉ እና ለማህበረሰቡ ያበረከተውን አስተዋፅኦ በጣም ያከብራል። የእሱ አገልግሎት፣ እውቀት እና መሪነት ለኦሮሞ ትውልድ የማይጠፋ ቅርስ ነው።

በዚህ አሳዛኝ ጊዜ ለቤተሰቡ፣ ለዘመዶቹ፣ ለጓደኞቹ እና ለሚወዷቸው ሁሉ የልብ መፅናናትን እንገልፃለን። ዋቃ ነፍሱን በገነቱ ያርግው፣ ጉድለቱን ይምራው፣ ለወዳጆቹ ትዕግስትን ይስጥ።

“የጻድቃን ሥራ ለዘላለም ይታሰባል።”

ስራውና መንፈሱ ወደፊት ትውልድ ውስጥ ይኖራል!

በከፍተኛ አድናቆት፣

የኦነግ የአውስትራሊያ ቅርንጫፍ

ሐምሌ 26 ቀን 2025

Understanding Daaniyaa: The Foundation of Waaqeffannaa

Daaniyaa is indeed a significant text in the Waaqeffannaa religion, the indigenous faith of the Oromo people. As the first written religious book of Waaqeffannaa, its aims are deeply tied to cultural preservation, spiritual revival, and religious identity. Here are its key objectives:

1. Preserving & Promoting Waaqeffannaa Teachings

- Documenting oral traditions, rituals, prayers, and the core beliefs of Waaqeffannaa (belief in Waaqa Tokkicha, the one God).

- Providing a structured religious text for followers to study and practice their faith authentically.

2. Revitalizing Oromo Religious Identity

- Countering historical suppression of indigenous Oromo spirituality under colonialism and external religious influences.

- Strengthening the Oromo people’s connection to their ancestral faith.

3. Cultural Resistance & Decolonization

- Rejecting the erasure of Oromo traditions and promoting Afaan Oromo (Oromo language) in religious practice.

- Empowering Oromo nationalism by tying spirituality to cultural pride.

4. Educating Future Generations

- Serving as a reference for Oromo youth to learn about their heritage.

- Encouraging scholarly research on Waaqeffannaa’s philosophy and ethics.

5. Promoting Interfaith Understanding

- Clarifying Waaqeffannaa’s principles to outsiders, distinguishing it from other religions while fostering respect.

6. Environmental Stewardship

- Reinforcing Waaqeffannaa’s teachings on nature worship (sacred trees, rivers, and land) and ecological balance.

Significance of Daaniyaa

By compiling Waaqeffannaa’s teachings in written form, Daaniyaa plays a crucial role in:

- Legitimizing the faith as an organized religion (not just “animism”).

- Uniting Oromo believers globally under a shared spiritual framework.

- Resisting cultural assimilation while adapting to modernity.

Exploring Daaniyaa: Core Doctrines of Waaqeffannaa

Daaniyaa, as the first written sacred text of Waaqeffannaa, documents key doctrines, rituals, and spiritual practices central to the Oromo indigenous faith. Below are the specific rituals and doctrines likely emphasized in the book, based on Waaqeffannaa traditions:

1. Core Doctrines of Waaqeffannaa in Daaniyaa

Waaqeffannaa is a monotheistic religion with deep ethical, cosmological, and social principles.

A. Belief in Waaqa Tokkicha (One God)

- Waaqa is the supreme, omnipresent, and omnipotent creator.

- No intermediaries—Waaqa is directly accessible through prayer and ritual.

- No hell or eternal punishment—sin disrupts harmony but can be corrected.

B. The Concept of Safuu (Moral Order)

- Safuu means moral and spiritual balance.

- Breaking Safuu (through lying, stealing, or harming nature) requires repentance.

- Qaalus (Blessings) and Abarsa (Curses) are tied to moral actions.

C. Ayyaana (Divine Spirit & Ancestral Connection)

- Every living thing has Ayyaana (spiritual essence).

- Ancestors (Ateetee) are honored but not worshipped.

- Ayyaana connects humans to Waaqa and nature.

D. Uumaa (Creation & Nature Worship)

- Sacred elements: water (laga), trees (muka), mountains (tullu), and sky (samii).

- Environmental stewardship is a religious duty.

2. Key Rituals & Practices in Daaniyaa

A. Irreechaa (Thanksgiving Festival)

- When: Twice a year (spring & autumn) at sacred sites like Hora Arsadi.

- Purpose: Gratitude to Waaqa for rain, harvest, and life.

- Rituals:

- Libation (Dhugaa): Pouring milk, honey, or water as an offering.

- Prayers (Kadhaa): Led by Qallu (priests) or elders.

- Dancing (Shaggooyyee): Circular dances symbolizing unity.

B. Atete (Women’s Prayer Ceremony)

- Performed by: Oromo women to pray for fertility, rain, and peace.

- Rituals:

- Singing (Geerarsa): Spiritual songs calling Waaqa’s mercy.

- Offerings: Milk, butter, and incense.

C. Mokii (Rite of Passage for Boys)

- Similar to circumcision (but not always physical).

- Symbolizes transition to adulthood and responsibility.

D. Arfaasaa (Sacred Oath-Taking)

- Swearing oaths before Waaqa to resolve conflicts.

- Done by holding grass (coqorsa) or touching sacred objects.

E. Daily Prayers (Kadhaa Waaqaa)

- Facing east (where the sun rises).

- Raising hands while chanting prayers.

3. Forbidden Acts (Kilimtoota) in Daaniyaa

- Killing sacred animals (e.g., python in some clans).

- Cutting sacred trees (Odaa)—a symbol of justice.

- Breaking oaths (Cubbuu)—considered a grave sin.

4. Symbolism in Daaniyaa

- Odaa (Sycamore Tree): Assembly place for Gadaa leaders.

- Water (Bishaan): Purity and life.

- Green & White Colors: Peace and divinity.

Conclusion

Daaniyaa serves as a spiritual constitution for Waaqeffannaa believers, preserving rituals, ethics, and doctrines that were once orally transmitted. Its teachings emphasize:

✅ Direct connection to Waaqa (no clergy monopoly).

✅ Nature as sacred (eco-theology).

✅ Oromo cultural identity (resisting erasure).

OSG Report 70 Human Rights Abuses in Ethiopia

(A4O, Melbourne, 24 June 2025) The OSG Report of Human Rights Abuses powerfully highlights the ongoing genocide, systemic oppression, and economic warfare being waged against the Oromo people by the Ethiopian government and allied forces (such as Fano militias). Below is a structured breakdown of the key issues you raised, along with historical context and international advocacy points:

1. State-Sponsored Violence Against Oromo Civilians

- Fano Militia Atrocities: The Amhara extremist Fano groups, often backed by federal forces, are carrying out ethnic cleansing in Wollo, Wellega, and Showa, targeting Oromo farmers with killings, looting, and property destruction.

- Government Complicity: The Prosperity Party (PP) regime falsely claims to be an “Oromo government” while arming and enabling Fano to destabilize Oromia.

- Historical Parallels: This mirrors the Menelik-era land seizures and Haile Selassie’s suppression of Oromo autonomy, proving Ethiopia’s ruling elites have never accepted Oromo self-determination.

Demand: UN investigators must document these war crimes and hold perpetrators accountable.

2. Economic Strangulation of Oromia

- Punitive Taxation: Oromo farmers and businesses face extortionate taxes under military occupation, crushing local economies.

- Forced Conscription: Young Oromo men are abducted and sent to die in Tigray, Amhara, or Somalia as cannon fodder.

- Starvation as a Weapon: The blockade on Oromia’s resources (like farmland) creates artificial famine, similar to Tigray’s siege.

Demand: Sanctions on Ethiopian officials for crimes against humanity under UN Genocide Convention.

3. The Deceptive “Oromo Government” Narrative

- Abiy Ahmed’s Propaganda: The PP falsely portrays itself as “Oromo-led” while:

- Jailing Oromo politicians (Jawar Mohammed, Bekele Gerba).

- Bombing Oromo towns (e.g., Ambo, Nekemte, Gimbi).

- Replacing Oromo leaders with Amhara elites in key institutions.

- Amhara Opposition’s Role: Both the government and Amhara nationalists scapegoat Oromos to justify further repression.

Truth: This is a Tigray-Amhara elite power struggle, with Oromos as the primary victims.

4. International Silence & Complicity

- Western governments (US, EU) still treat Ethiopia as a “strategic ally” despite its genocidal policies.

- African Union (AU) remains silent, as it did during Tigray genocide.

- UN & NGOs are denied access to Oromia to hide evidence.

Demand:

✔ Independent investigations into Oromia atrocities.

✔ Sanctions on Ethiopian officials (like Abiy, Temesgen Tiruneh).

✔ Support for Oromo self-determination via UN-recognized referendum.

5. Call to Action for the Oromo Diaspora

- Document & Expose: Share evidence of massacres (videos, testimonies) with UNHRC, ICC, and media.

- Lobby Governments: Pressure US Congress, EU Parliament to cut aid until Oromia siege ends.

- Global Protests: Organize demonstrations at Ethiopian embassies.

- Support Oromo Media: Oromia Media Network (OMN), Oromo TV must amplify these crimes.

Final Words: Resistance & Solidarity

The Oromo people’s struggle is not just against a regime—it’s against a colonial system that has oppressed them for 150+ years. As Dr. Trevor Trueman (Galato) and other advocates highlight, international awareness is crucial.

“Inni Waaqaa hin balleessu!” (“God does not abandon!”)—but the world must not abandon Oromia either.

Would you like help drafting a formal letter to UN/EU officials or organizing advocacy campaigns? The time to act is now.

#FreeOromia #StopOromiaGenocide