April 15th is the Oromo Martyrs’ Day, also known as Guyyaa Gootota Oromoo. This commemorative day was first started by the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) after the executions of its prominent leaders on a diplomatic mission en routed to Somalia on April 15, 1980. Since then, this day has been observed as the Oromo Martyrs’ Day by Oromo nationals around the world to honor those who have sacrificed their lives to free Oromia, and to renew a commitment to the cause for which they had died.

Why April 15th?

Mid 1978-1979 is remembered as the period when the survival of the Oromo national liberation struggle, led by the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA), was under a severe threat of extinction. It was feared that OLA units in Arsi, Bale and Hararghe would disintegrate, and their channel of connection and supplies would be cut off by the Dergue army that just recuperated from the Ethio-Somali war. Upon defeating the Siad Barre army, the Dergue turned its face on OLA. The OLA, in the fronts of Arsi, Bale and Hararghe, fought steadfastly and scored victory over the Dergue army and regrouped once again on January 1st 1980. In the wake of their military victory, OLF intensified its political struggle inside the country and abroad. The initial political victory included the persuasion of the Siad Barre government to allow the opening of OLF office in Mogadishu, Somalia, in 1980, to serve as a center of consultation and deliberation between OLF political and military leaders.

In the same year, a ten-member high-ranking military and political delegates (see list below) were on their way to Somalia to meet with political leaders there when they were captured by Somali bandits in Shinniga desert (in Ogaden). These bandits were members of a splinter group from the Siad Barre army that harbored bitter hatred towards Oromo and the OLF. These bandits abused and severely tortured their Oromo captives. The bandits finally ordered the Muslims and Christians to segregate before their executions. The Oromo comrades chose to stay together and face any eventualities than identifying themselves as nothing else, but Oromo. On the day of April 15, 1980, all the ten were executed and their bodies thrown into a single grave.

Reasons for Celebrating the Oromo Martyrs’ Day

There are four major reasons why we commemorate this day.

First, this day allows us to remember those Oromo heroines and heroes who sacrificed their lives to restore Oromo culture, identity, and human dignity that were wounded by Ethiopian colonialism. In other words, this commemoration assists us to recognize the dialectical connection between martyrdom, bravery, patriotism and Oromummaa. Until Oromo heroes and heroines created the OLF and maintained its survival by paying ultimate sacrifices, Oromo peoplehood, culture, language, and history were dumped into the trashcan of Ethiopian history. These heroes and heroines had clearly understood the significance of Oromo culture, history, language, and identity in building Oromummaa, and victorious consciousness to consolidate the Oromo national struggle for achieving Oromian statehood, sovereignty, and democracy.

Second, this commemoration day reminds us that Oromo liberation requires heavy sacrifices, and those who have given their lives for our freedom, are our revolutionary models. Such patriots created dignified history for our nation.

Third, this day reminds us that we have historical obligations to continue the struggle that Oromo martyrs started until victory.

Fourth, this celebration helps us recognize that Oromo heroes and heroines are still fighting in Oromia today. Overall, those Oromo patriots, who by luck have survived and continued the difficult and complex struggle, deserve recognition and respect for what they have done for their people. We must protect them from lies and propaganda of the internal and external enemies. Without the persistent efforts of our patriots, the multiple enemies of the Oromo nation would have destroyed the OLF a long time ago. This does not mean that we do not criticize them when they make mistakes. It is the responsibility of Oromo nationalists to develop constructive criticisms to strengthen our national movement.

The Oromo leaders and members of the OLF, who ignited the fire of Oromummaa or Oromo nationalism, whether dead or alive, have been the foundation and pillar of the Oromo national movement. They left their families, wives, husbands, houses, professions, and children by choosing Oromo human dignity and freedom. By making these kinds of difficult choices, they confronted suffering and death. Consequently, they opened a new historical chapter in our history, and showed to us new possibilities by taking risky and courageous actions. Today, Oromo heroes and heroines are engaged in the Oromo struggle; members of the OLA, Oromo activist students and other activists are our contemporary heroes and heroines, who are intensifying the struggle. All Oromos all over the world who demonstrate their support and sympathy for the Oromo national struggle by contributing whatever they can for these brave men and women are also engaged in patriotic and brave activities.

We, Oromos in exile/Diaspora, should follow the footsteps of the fallen and surviving Oromo heroes and heroes by contributing anything we can to support the Oromo national struggle. If the fallen Oromos had paid with their lives to liberate us, how can we fail to contribute our time, money and expertise to liberate our beloved country, Oromia? How can we sleep when our mothers, daughters and sisters are raped in Oromia? How can we be at peace when genocide is committed on our people? Since our people live under Ethiopian political slavery, and since no country supports the Oromo struggle, we must fulfill our historical obligations by supporting the Oromo national struggle.

April 15th is then chosen to be a day of remembrance for these and all other martyrs, who died in any month and season of the past 120 years of the Oromo anti-colonial struggle.

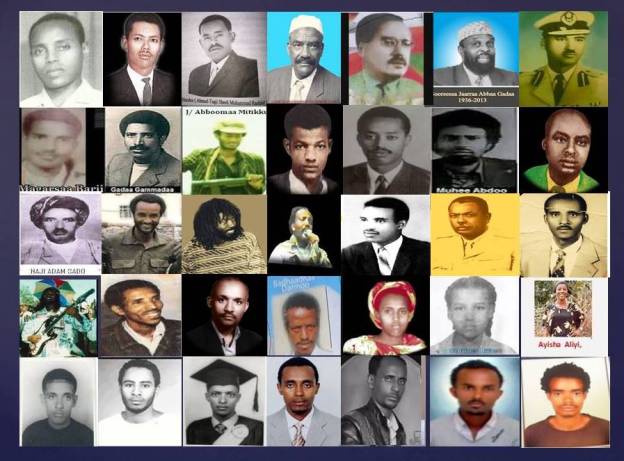

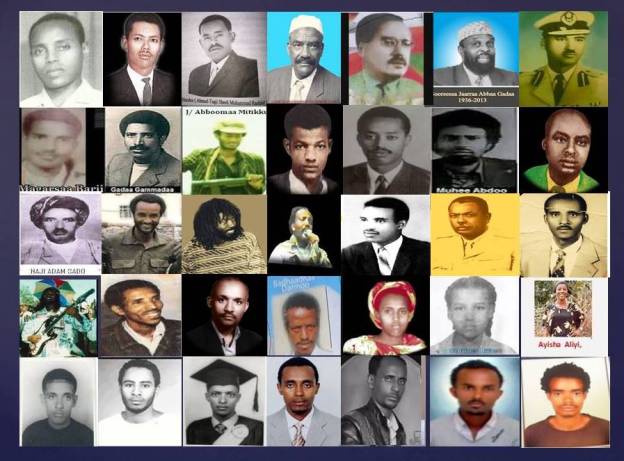

The following Oromo leaders were martyred on April 15, 1980

1. Bariso Waabii (Magarsaa Barii)

2. Gadaa Gammadaa (Demise Tacaane)

3. Abbaa Xiq (Abboma Mitikku)

4. Doori Barii (Yiggazu Banti)

5. Falmataa (Umar, Caccabsaa)

6. Fafamaa Doyyoo

7. Irrinaa Qacale (Dhibaa)

8. Dhadhachaa Mul’ataa

9. Dhadhachaa Boruu

10. Marii Galaan

Our martyrs lost their lives while dreaming and fighting for freedom, justice, democracy, and development of their people and their country. They recognized that agitating, educating, organizing, and mobilizing a colonized and dehumanized nation for liberation requires courage, determination, bravery and self-sacrifice without fear of suffering and death in the hands of the enemy and their collaborators. We have moral and national responsibilities to achieve the objectives for which our heroines and heroes sacrificed their lives. The Oromo national movement is a very dangerous project. Tens of thousands of our people have been imprisoned, tortured, raped, and received all forms of abuse from successive Ethiopian governments in general, and that of the Meles Zenawi in particular. The Tigrayan-led government has been systematically targeting and killing all Oromo leaders and those who have potentials of leadership while promoting the most despicable elements of Oromo society and the children of colonial settlers as leaders of the Oromo nation.

While commemorating our fallen heroes and heroines, we must also remember our current ones who are engaging in the bitter struggle and those who are suffering in Ethiopian prisons. We must double our support for the OLA that is engaging in implementing the missions of the fallen Oromo heroines and heroes in Oromian forests, valleys, mountains, and Ethiopian garrison cities. We should sustain the spirits of our fallen heroes and heroines by taking concrete actions every day. It is our national responsibility to educate, mobilize and recruit passive or unconscious Oromo individuals to join the Oromo national movement. Such actions must start in families by educating and training children; husbands and wives must teach one another and their children the essence of Oromoummaa. The spirits of our heroes and heroines require that all of us must be grass-root leaders who engage in a systematic struggle to fight those agents of the enemy or those misled individuals who undermine the Oromo national struggle intentionally or unintentionally.

All Oromo nationalists must be cadres, teachers, students, leaders, followers, fighters, financiers, ideologues, organizers, defenders and promoters of the Oromo cause. We should not keep quiet when certain individuals attack our organizations, leaders, communities and Oromo peoplehood to satisfy their troubled egos or their masters. If we do some of these activities in our daily lives, the spirits of our fallen heroes and heroines will survive through our actions.

May the spirit of April inspire in all of us a profound, genuine and transcendent sense of unity, commitment, and overall renewal that the time demands – for that is what it takes to advance the Oromo freedom struggle in this most critical times.