Author Archives: advocacy4oromia

IRREECHAA: THE CHERISHED OROMO HERITAGE AND ITS CHALLENGING TASK

Getaachew Chemeda ( Member: Gadaa Meelbaa)

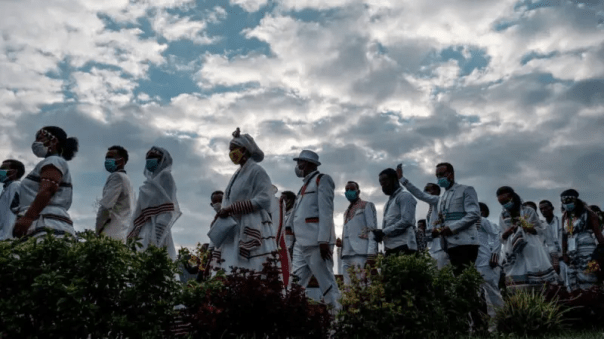

Since time immemorial Oromo men, women, youths, and elders have been rallying together to express thanks and happiness to their Waaqa, who according to the Oromo concept of colour is symbolised by the colour gurraacha, meaning black. By its very original concept the colour gurraacha (black) did not stand for mourning, grief or for the expression of sorrow. It was used to symbolise the invisible supreme power that can do and undo anything anywhere in the universe. Having this narrative tradition in mind, the Oromos have been getting together around rivers or lakes to thank their Waaqa Gurraacha at the end of the rainy season. They strongly believe that, it was Waaqa who delivered them from the restraining rainy season and brought them to the cherished floweryseason. This great event, called Irreechain AfaanOromoo, is celebrated every year at the end of September or in the first week of October. https://youtu.be/Pk3W49aKXDY

Irreecha holds an important social event in Oromo people’s aspiration for peace, prosperity, abundance, fertility, and a hope for the renewal of a new social life. Like ancient Egyptians who used to celebrate the yearly inundation of the River Nile as a symbol of life giving, Oromos have been celebrating their new year on the side of river banks or lakes which, according to Oromo mythology, is the source of all life. Some of the hymens ancient Egyptians sang while praising the Nile were:

Oh Nile! You rise out of the earth and come to nourish Egypt! You quench the thirsty desert! You bring forth the barley! You create the wheat! You fill the granaries and the storehouses, not forgetting the poor. For You we pluck our harps, for You we sing! [1]

Creation Narrative Stories

It was not only the ancient Egyptians or the Oromos who had creation stories in relation to water. In the Japanese telling stories, we find water holding the core of the dawn of creation. First, there was an ocean, out of which the many Japanese Islands were believed to have been created. There was a god known as Izanagi and a goddess Izanami. The gods, as a couple, had three children, of whom the grandson of the Sun Goddess had become the first Emperor of Japan, Nippon, as known to the native population.[2]

The gods used a long spear and stirred up mud at the bottom of the ocean. It was out of the stirred up mud those more than 6000 Japanese islands were believed to have been created. On the eastern side, out of the glittering Pacific Ocean, the sun rose every morning. It was the cherished sun’s rays which had a big role in illumining, nourishing, and bringing up the Japanese archipelagos to life. This is the Japanese thought of their land, Mount Fuji being the most beautiful and sacred one.[3]

For the Japanese, Japan has not only been their country. Japan has been their world and their religion. The creation story the people share in common and the passionate love they have for their country has continued to make up the coherent faith of their oneness. And, out of the cherished mythology, they have undoubtedly benefited enormous groundwork principles for their social and technological advancement we are witnessing today.

When we come to the antique Scandinavians of northern Europe, we find similar watery creation stories. In the beginning there was an abyss filled with water. The water froze; and lastly melted down. Out of the melted water, a giant being of human form called Ymir emerged. Thereafter, a man and woman were created out of Ymir’s armpits. In short, this was the beginning of ancient Scandinavian telling stories about the myth of human creation.[4]

The Oromo myth of creation holds the view that water being the source of androgynous being. According to Oromo narration story, by the unfathomable wisdom of Waaqa Gurraacha, the androgyny was divided in to two parts and became male and female. After the division, the two opposite sexes began to live separately on the either side of the river. Though they were able to see each other across the river, they were hampered from joining each other by the overflow of the river. When the river subsided and sank down into its course, during the flowering season, they were able to cross the river and embraced each other.[5] Here was the point, during the flowering season, according to Oromo belief, when the first gaa’ila (engagement for marriage) started to blossom.

Many of us may remember when newly married Oromo couples were coming to Irreechaat Hora Harsadii, enforced by nobody but only inspired by the tradition to get the blessings of the hayyuus and Abbaa Gadaas. But that was not performed on October 2, 2016 because of the heinous massacre carried out by the incumbent Ethiopian regime that disrupted the whole process of the ceremony.

Having this entire narrative story in mind, defending and combatting all challenging obstacles and heinous crimes imposed on them, the Oromos have continued to celebrate their yearly thanksgiving Irreecha festival, dressing beautiful national costumes suited for the occasion.

Norms of Irreecha Celebration

Today, at national level, millions of Oromos are celebrating Irreecha Birraa, on the side of Hora Harsadii in Bishooftuu town. At national or local levels, there are traditionally agreed upon norms that govern the whole process of the ceremony from the beginning to the end, which is deeply rooted in the strongly and humanely established Oromo views for peace, love, prosperity, and human dignity. Based on Oromo clans’ successive generation by birth, there are individuals who offer blessings first, second, and so on. This is dually (angafaa fi qixisuu) restructured in Oromo kinship organisations whose function of check and balance has become basic foundation for the indigenous Gadaa Oromo Democracy to flourish.

The ceremony commences first by offering thanks and greeneries to Waaqa, followed by blessing all creatures of Waaqa to be at peace with each other.They also give admiration and honour to Waaqa’s wisdom who gave them a perfect bliss of land with abundant natural resources. This is one of the inherent reasons why the Oromos are cherishing their ancestral homeland, Oromiyaa (Biyya Oromoo) as part of their natural right, be it in peace or war times.

In the case of Irreecha Birraa, it is the Abbaa Malkaa who ‘opens the door’ of the malkaa (river) by charmingly welcoming those who arrived at the site in peace.[6] Those distinguished hayyuus from senior and junior clans (mana angafaa fi qixisuu) and the Abbaa Gadaa from the incumbent Gadaa party are traditionally honoured to take leading positions in giving thanks and blessings to all. Even the Ayyaantu-Qaalluus, who are believed to be the guardians of the laws of Waaqa and the custodians of Oromo traditional religion, have no seniority right to claim either to take the leading position or to give blessings first. They have their own defined time and place to do so. Failure to honestly follow those agreed upon traditional charter, could lead to chaos and eventually to the disintegration of the society. Nevertheless, despite so many apartheid walls erected among Oromo regions by builders of the imperial palace of political Ethiopia (in contradiction to historical Ethiopia), the Oromos are not able to be divided by the walls. They are chiselling down the walls and are patiently moving forward in unison.

Is Irreecha a Religion?

As common to any Oromo meetings or conferences, thanking Waaqa and blessing each other precede the opening of the agenda of the meetings. There is no exception for the thanksgiving Oromo new year celebration, Irreecha. Since the Oromo name of Waaqa is the centre of Oromo Natural Religion, the solemn invocation of Waaqa at Irreecha or elsewhere cannot be avoided. This is the core issue, the authenticity of Oromo natural religion and Oromo morality that seem to have scared general managers of ‘Revelation Industries’ and their sponsors in Oromia. They are prompted to develop phobic images against essential Oromo values: vilifying, desecrating, defaming, and bedevilling Oromo material and spiritual assets as a whole. Why? The answer is so unilineal, not parallel.

Irreecha has been one of the major Oromo events that distinguishes, makes, and marks the identity of an Oromo personality as a member of the nation.

- It is a social festival that praises Waaqa who helped them come together in peace and embrace the incoming bright-sunny season.

- It is a social festival that sees off the out-going rainy season, wishing its recurrent appearance in peace, happiness, abundance, fertility, equality, fraternity and a hope for victory against all forms of evils.

But, as has obviously been duplicated by foreign media outlets, particularly after the Irreecha massacre of October 2, 2016, there is a clear tendency to look on Irreecha as a ‘religious festival’. It is quite villainous and sinisterial to depict the general Oromo sense of Oromo-self only from a single perspective. Is Habasha’s Inkutatash not Qiddus Yohannes’ religious celebration or is it a new year festival? Is Tigrian’s Ashanda the worshipping of Churches of Saints or season greetings? Is European Christmas the celebration of Christ’s birth day, or is it the continuation of pre-Christianity European culture of winter solstice celebration?

When it comes to Irreecha Oromo, it is propagated as heathenish or animist religion that makes a tree or a river the centre of worship. This can simply be attested from the recently publicised sub-human propaganda by a self-declared “Prophet” named Suraphael Demise. https://youtu.be/u2hrjMaSeqM

We do not understand whether such inconsiderate propaganda is really a reflection from a fully developed human brain or is it a proxy psychological war sponsored by the monstrous Satan.

If one wants to talk or know about Oromo religion, it is called Waaqeffanna, not Irreecha. Where is the self-organised Waaqeffannaa religion right now? One may ask the Tigrian Ethiopian regime, sitting in Minilk’s imperial palace; muddling the peoples of that empire, sponsoring divisive and xenophobic people like Suraphel Demise.

Waaqeffannaa by its natural origin, contrary to revelationists’ assertions who claimed to have seen visions and heard voices, is neither a claimed vision nor claimed heard voices. Had it been a claimed vision or claimed voices, it could have been dwelling on narrating about a place of everlasting torture or about a place of eternal delight in the afterlife. In the narrative story telling of Waaqeffannaa there were no individuals who did claim any visions or heard voices for its establishment as a religious institution. It emerged naturally out of the organised Oromo people’s activities in the remote antiquity. Henceforth, Waaqeffannaa, as a natural religion, has become the common vision of Oromo people’s common mind. It is free from claiming any received information of the afterlife, be it from the chamber of the sinners or from the chamber of the pious. However, Waaqeffannaa may wonder or speculate what could be happening beyond the veil of a man’s soul (lubbuu) after his dead body was ceremonially buried. Revealed religions claimed and are still claiming that they had unveiled the veil, saw the souls, and heard their voices from chambers of the ‘hell and heaven’.

In its strictest sense, Irreecha is not a religious institution. It is a ritualised social event; certainly, adorned and accompanied by Oromo Natural Religion known as Waaqeffannaa. Waaqeffannaa and Irreecha have been with the Oromos, by the Oromos, and for the Oromos since the dawn of creation long before the conception of revealed religions.

The Irreecha Massacre and the “Tasa” Monument

An attempt to ban the Irreecha festival started the time when Oromos lost their sovereign rights to Abyssinian firearms under the supreme commandship of King Minilk of Shewa. After the Tigrian-led Ethiopian regime took the imperial palace by force in 1991, the orchestration to ban the Irreecha ceremony was concluded. This time, the regime took the first apartheid action by banning the revived Matcha-Tulama Self-Help Association and the freely organised Waaqeffaanaa religious association. Instead of directly banning Irreecha, however, like Matcha-Tulama and Waaqeffanaa, the regime renewed the old Nugus-Orthodox tactics of hijacking anything good of the Oromos and good for the Oromos.

A delegate led by Abba Duulaa Gammadaa, the then president of ‘Oromia Regional State’ was despatched to Hora Harsadii to hijack Irreecha. The delegate failed to accomplish the mission it intended to seal and returned to the palace in dismay. Here was planted the seed of the evil action that took thousands of innocent lives on October 2, 2016 at Hora Harsadii, Bishooftuu.

Ahead of the massacre, the regime meticulously orchestrated provocative tactics that could incite the people against itself. It imposed rules that are too antagonistic to the established Irreecha tradition. When the people reacted to the evil provocation, its ill-behaved security forces started firing life bullets from the ground and from armoured vehicles against millions of celebrants. Military helicopter flew over them spraying teargas on them. On this day, that barbaric action changed the happy Oromo Irreecha event to a bloody grief. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R_3miIwY4mQ&t=33s

The regime and its killing forces rejoiced the success of their fascistic actions on human carnages. The regime’s trumpet Prime Minister, Haile Mariam Desalegn, was so quick to deny the massacre and said, “No single bullet was heard; but because of stampede about 52 people were killed.” Finally, like Muktar Kadir who thanked the Agazi killing forces, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister thanked the regime’s mercilessly firing forces https://youtu.be/Q6cSzgiZdc8

To remember the success of their evil plan, the Tigrian-Ethiopian regime erected a very offensive stone they call “Memorial Monument”. A deaf monument, that speaks of nothing about the root cause of the massacre. Sadly, what is inscribed on the monument seems to be articulated in the way it could depict the lost human lives as unworthy ones. It reads in Afaan Oromoo “Tasa Lubbuun Isaanii dabreef, for suddenly passed away lives”

This “Tasa Monument” was erected in a faraway place where the actual massacre did not take place

Conclusion

The Oromos have tried to do everything positive for Ethiopia. But why are they being reciprocated with negativity for their positive generosity? When the Oromos are coming out for peace, those who are making huge business in the name of “Ethiopia” are incessantly confronting them with vibrant forms of violence, persecution and marginalisation.

In former days, before Oromo country and their central holy site, Walaabu, had fallen to naftenya’s bayonet, Oromo generations in every Oromo clan were making pilgrimage to Walaabu. The purpose of the journey was more of religious, that they sought the anointment and blessings of Abbaa Muudaa, who was believed to be the eldest son of Oromo [Orma], the Spiritual Father of the nation holding the centre of Oromo Natural Religion, the belief in Waaqa Tokkicha.[7]

The pilgrims, who were scattered in north-east Africa, representing their clans, used to travel a long journey and arrived at the Muuda site.On their return to their clans, they came back with qumbii (myrrh), which the Abbaa Muuda distributed to them as a symbol of his fatherly holy blessings. This had been considered as dangerous and anti-peace to Abyssinian crosses and crowns. Subsequently, with the invention and consolidation of the ‘New Ethiopia’, qinyi gizaat, (the Amharic version for colonial empire) by King Minilik of Shewa, Oromo’s journey to the Muuda holy site was prohibited. It was finally banned at the beginning of the twentieth century. Huntingford who collected good information from various sources wrote:

”—after the Abyssinian conquest of [Oromia], however, the pilgrimage was forbidden owing to its political and nationalistic influence.—as opportunities for stirring up Oromo patriotism and forming plans of rebellion for men of all the Oromo tribes met at Walaabu.”[8]

This inhumane and erratic ideology will get nowhere. It is now far from halting down Oromo people’s aspiration for regaining their lost freedom. We, including those in ati-Oromo camps, are daily watching and witnessing the reality on the ground. The more direct wars and propaganda campaigns are pouring on the Oromos, the more their heroisms are reinvigorated. Irreecha will continue to march forward with its noble objectives of thanksgiving social festivities: vitalising, remaking, and remarking Oromummaa (Oromo-ness).

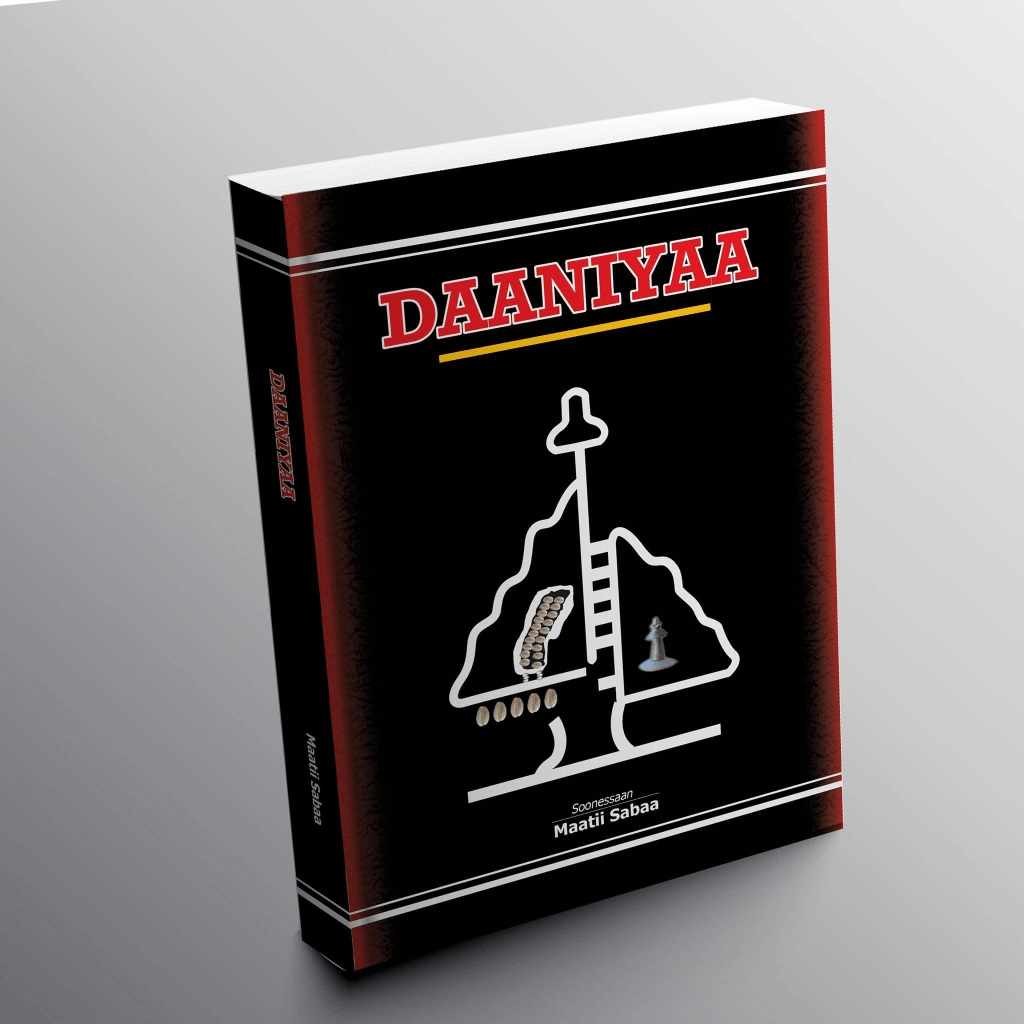

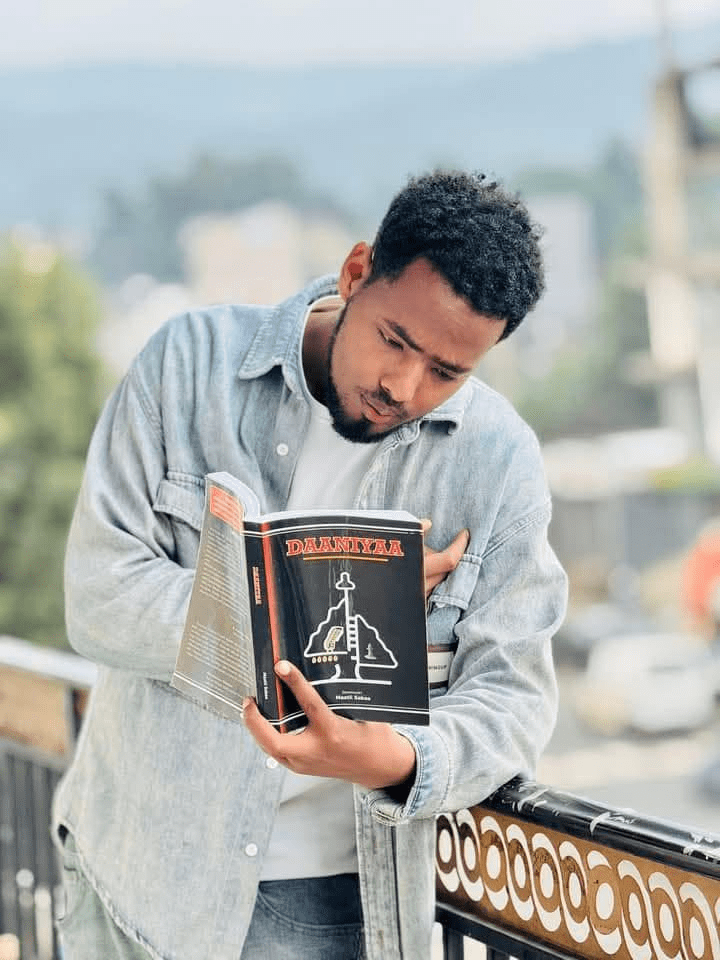

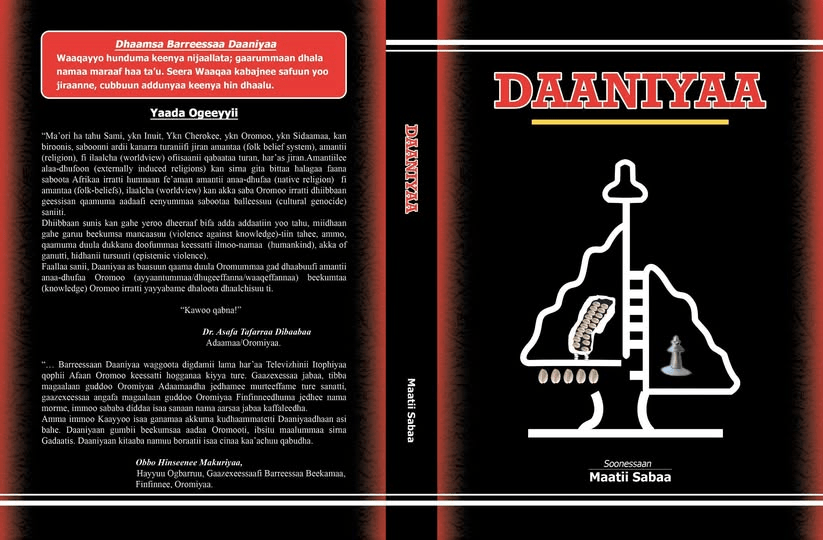

Daaniyaa: Spiritual Foundations of Oromo Religion

Daaniyaa refers to the foundational written sacred text of Waaqeffannaa, the indigenous religion of the Oromo people. It serves to preserve Oromo culture and spirituality by documenting core beliefs in Waaqa Tokkicha (One God), moral principles like safuu (spiritual balance), and ancestral connections (Ayyaana). The text is crucial for religious identity, education, and promoting the Oromo language and heritage.

Key Aspects of Daaniyaa

Religious Foundation: Daaniyaa is the first written book for Waaqeffannaa, a monotheistic faith centered on the worship of Waaqa Tokkicha.

Preservation of Culture: The book documents oral traditions, rituals, and the philosophy of Waaqeffannaa, helping to counter historical suppression and preserve Oromo spiritual identity.

Core Beliefs: It details key doctrines, such as the belief in a single creator god, the importance of safuu (moral order), the concept of Ayyaana (divine spirit and ancestral connection), and reverence for natural elements.

Oromo Identity and Decolonization: Daaniyaa plays a role in Oromo cultural resistance and decolonization by promoting the use of the Afaan Oromo language in religious practice and connecting spiritual practices to cultural pride.

Education and Research: The text is intended to educate future generations about Oromo heritage and serve as a basis for scholarly research into Waaqeffannaa’s ethics and philosophy.

What are the main teachings of Daaniyaa in Waaqeffannaa?

The main teachings of Daaniyaa in Waaqeffannaa center on belief in one supreme creator (Waaqa Tokkicha), the importance of moral order (Safuu), ancestral connection through Ayyaana (divine spirit), and reverence for nature.

Belief in Waaqa Tokkicha

Waaqeffannaa teaches that Waaqa, the one God, is omnipresent and omnipotent, and directly accessible to every believer without intermediaries.

Safuu (Moral and Spiritual Order)

Safuu represents ethical conduct, social justice, and spiritual balance; violating Safuu through dishonesty, theft, or harm to nature requires repentance.

Ayyaana (Ancestral & Divine Connection)

Ayyaana denotes spiritual ties to ancestors and the divine spirit, reinforcing the Oromo people’s bond with Waaqa and maintaining cultural identity.

Rituals and Practices

Important rituals include daily prayers facing east (Kadhaa Waaqaa), rites of passage (Mokii), and sacred oath-taking (Arfaasaa) to resolve conflicts. Symbolic use of natural elements like the Odaa tree and water highlight the eco-theology of Waaqeffannaa.

Prohibition of Forbidden Acts

Daaniyaa prohibits killing sacred animals, cutting sacred trees, and breaking oaths—considered grave sins.

Role in Oromo Identity

The text strengthens Oromo spiritual identity, promotes the use of Afaan Oromo in religious practice, and acts as a tool of cultural resistance and decolonization.

Environmental Stewardship

Waaqeffannaa and Daaniyaa emphasize nature worship, ecological balance, and stewardship of the land.

These core teachings make Daaniyaa a spiritual constitution for followers of Waaqeffannaa, codifying doctrines, rituals, ethics, and the importance of cultural heritage.

What are the main rituals described in Daaniyaa?

The main rituals described in “Daaniyaa,” the foundational sacred text of the Oromo indigenous religion Waaqeffannaa, include:

Irreechaa (Thanksgiving Festival): Held twice a year during spring and autumn at sacred sites like Hora Arsadi, this ritual involves offering libations (milk, honey, water), prayers led by Qallu (priests) or elders, and communal dancing symbolizing unity. It expresses gratitude to Waaqa (God) for rain, harvest, and life.

Daily Prayers (Kadhaa Waaqaa): Practiced facing east at sunrise, involving raising hands and chanting prayers.

Forbidden acts include killing sacred animals or cutting sacred trees, and breaking oaths is considered a grave sin. Symbolically important elements are the Odaa (Sycamore Tree), water, and colors green and white, signifying peace and divinity.

These rituals and spiritual practices emphasize a direct connection to Waaqa, moral order (Safuu), respect for nature, and preservation of Oromo cultural identity.

The book “Daaniyaa,” which is the foundational written sacred text of Waaqeffannaa, the indigenous religion of the Oromo people, was authored by Maatii Sabaa.

𝕀𝕣𝕣𝕖𝕖𝕔𝕙𝕒𝕒: The Oromo Festival of Thanksgiving and Renewal

Every year, as the rains recede and the Ethiopian highlands begin to glow with new light, millions of Oromo people gather to give thanks. Irreechaa — literally “thanksgiving” in Afaan Oromo — is a vibrant, deeply felt festival that marks the end of the rainy season and the welcoming of a new, fertile period. It is at once spiritual ceremony, community reunion, cultural showcase, and a time for renewal.

Roots and Meaning

Irreechaa is rooted in the traditional Oromo worldview and is closely linked to the Gadaa system, the democratic social and political institution that organized Oromo life for centuries. The festival is fundamentally a ritual of gratitude to Waaqa (God) for life, health, and the bounty of the land. It affirms social bonds, renews moral commitments, and marks seasonal and generational transitions. Though its spirit is ancient, Irreechaa remains a living, adaptive tradition that continues to shape Oromo identity today.

Where and When It Happens

Irreechaa is observed across Oromia and by Oromo communities worldwide. Celebrations are usually held at natural gathering places — lakes, rivers, and meadows — where people can perform water- and earth-centered rites. The largest contemporary gatherings often take place by the lakes near Bishoftu (sometimes also called Debre Zeyit) and at other prominent riverbanks and lakes throughout the region. The timing follows the agricultural and pastoral calendar: typically at the end of the rainy season, around late September or early October in the Gregorian calendar, though exact dates may vary by locality and community.

Rituals and Practices

An Irreechaa morning is a sensory feast. People travel from villages and cities, wearing traditional dress and carrying bunches of seasonal wildflowers and fresh grasses. The ceremony is usually led by elders and by the Abbaa Gadaa (the Gadaa father or leader), who offers prayers and blessings for the coming year.

Key elements include:

– Gatherings at water: People congregate at lakeshores and riverbanks, where water symbolizes renewal and life.

– Blessings by elders: The Abbaa Gadaa or elders lift a branch of grass or flowers — a symbol of life — and sprinkle or dip it in the water, then wave or sprinkle drops over the crowd as a communal blessing.

– Songs and ululation: Traditional songs, chants, and ululations (high-pitched celebratory cries) fill the place. Music and dance are central, with both communal steps and individual expressions.

– Feasting and fellowship: Families and friends share food, exchange greetings, and reconnect after the rainy months. Coffee ceremonies, a core part of Ethiopian hospitality, often accompany gatherings.

– Symbolic gestures: The sharing and tossing of flowers or grasses into the water is a visible act of giving thanks and wishing for fertility and prosperity.

Cultural and Civic Dimensions

Though Irreechaa is primarily a spiritual and cultural event, it has also taken on civic and social significance in modern times. Festivals have been occasions for public discussion, cultural revival, and the assertion of Oromo language and identity. For the Oromo diaspora — in North America, Europe, and beyond — Irreechaa gatherings are important moments for preserving heritage and passing it to younger generations.

The festival has not been without challenges. Large crowds require careful management, and political tensions at times have added complexity to peaceful celebrations. Communities and authorities increasingly work together to ensure safety while protecting the sacred and communal nature of the festival.

Why Irreechaa Matters

Irreechaa is more than an annual party: it is a ritual that knits people to place, to each other, and to the cycles of nature. It embodies gratitude, resilience, and hope — values that resonate far beyond Oromia. For visitors and observers, Irreechaa offers a window into a rich cultural tradition that balances spirituality, social cohesion, and joyful celebration.

If You Attend

If you have the opportunity to witness or participate in Irreechaa, approach with respect:

– Dress modestly and follow local customs.

– Ask permission before taking photos, especially of elders or religious activities.

– Participate quietly and respectfully in communal moments; observe before joining.

– Be mindful of large crowds and follow safety guidance from organizers.

Irreechaa remains a powerful expression of Oromo life: a time to say thank you, to heal, to celebrate community, and to step forward together into the new season.

#Irreecha#Irreechaa#Oromo#OromoFestival#OromoCulture#OromoTradition#OromoThanksgiving#Gadaa#SirnaGadaa

#Opinion: #Namummaa: Reviving humanity through #Oromo wisdom

The 75th Gadaa power transfer ceremony of Gujii Oromo was held in February 2024 (Photo: Social Media)

Addis Abeba – In today’s world, we must once again ask: What does it mean to be human? For me, this question is far from abstract. It is rooted in my lived experience in the Betcho district (1972–1988). I was born and raised in Betcho, in the Ilu Abba Bora Zone of the Oromia region, where Namummaa was not merely spoken of but practiced daily within the community. I witnessed humanness expressed not only through words but also in the way people related to one another and to nature.

Today, we live in an age of extraordinary possibility—and peril. Science is decoding the universe, technology is reshaping our lives, and yet, the human spirit often feels adrift. Conflict, ecological breakdown, and deep societal fragmentation define too much of our global experience. Even our systems of knowledge, governance, and progress frequently lose sight of the very human beings they are meant to serve.

It is time we ask again—not philosophically alone, but practically and urgently: What does it mean to be human? And how can we live in ways that regenerate, rather than degrade, our shared humanness?

Across continents and centuries, many traditions have attempted to answer this. In this moment of global reckoning, we offer one deeply rooted in the African Oromo worldview—Namummaa—as both ancient wisdom and a fresh ethical compass.

Namummaa: Living legacy of Oromo

As shared by the late Haji Boru Guyo during informal discussions (1998–2003), Namummaa is discussed as a lived ethic and everyday guidance, not as a theory. Their wisdom echoes in scholarship—for example, Asmarom Legese and Asefa Jalata document the Gadaa system as a great democratic and ethical tradition.

In the worldview of the Oromo people of Ethiopia, Namummaa is not a label. It is a lived ethic. A lifelong journey. A way of being. To this, the author’s childhood lived experience (1972-1988) as well as informal discussions (1998-2003) with the late Haji Boru Guyo are the living testaments.

At its heart, Namummaa means being fully human—not just in isolation, nor just in relationship to others, but through the integration of self-realization, social harmony, and moral alignment with the natural world.

This was no abstraction in Oromo society. It was nurtured intentionally from childhood, embedded in institutions like the Gadaa system (a sophisticated, age-based democratic governance model), and governed by Saffuu—a moral code that honored balance, respect, and responsibility to all life. The African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) posits Gadaa as the embodiment of democracy as it should be.

An in-depth study by Darwish & Huber (2003) discusses individualism vs. collectivism across cultures. Unlike many global ideologies that lean toward either rugged individualism or enforced collectivism, discussed in-depth by Namummaa, scored, Namummaa holds both in dynamic balance. Every person is guided to realize their full potential while being equally accountable to the well-being of others and the living world.

Michuu Namummaa: Regenerative framework

Recent scholarship, such as Bekalu Wachiso’s exploration of Namummaa as an indigenous peace philosophy and Geebi Jeo Wake’s framing of it as the Oromo gift to the world, reinforces Michuu Namummaa as both a rooted and globally relevant concept. To bring this ethical power into contemporary relevance, we propose a living framework: Michuu Namummaa—a regenerative model for what it means to be, live, and lead as a human in the 21st century.

This framework unfolds across three interconnected dimensions:

1. Essence: Recognizing and Honoring Humanity

This dimension entails embracing your own humanity through self-inquiry and authenticity. It also involves treating others as fellow human beings, beyond labels and identities, and showing respect for nature. The regenerative essence of Namummaa, as theorized by Bekalu Wachiso and Gerbi Jeo Wake, invites us to treat others with dignity and nature with reverence. This philosophy is not abstract; it is lived, as I witnessed in the Betcho district and heard echoed in conversations with elders like Haji Boru Guyo (1998–2003). As the saying goes, “Let every interaction become a site of dignity, not degradation.”

2. Living: Nurturing Potential and Togetherness

This dimension requires us to reframe how we raise children, educate citizens, and design institutions. It involves nurturing Namummaa to unleash both individual excellence and collective harmony, recognizing that transformation begins with awareness but only manifests through sustained action.

3. Excellence: Becoming Beacons of Namummaa

This final dimension involves cultivating people who embody humanity as a moral force and encouraging regenerative leadership—leaders who heal, not harm, and who create, not conquer. In his op-ed, Girma Gadissa asserts the need for a governance model that empowers the youth and harmonizes society, rather than perpetuating conflicts. The Gadaa system, explored in depth by Asmarom Legesse and Asafa Jalata, offers a model of excellence rooted in ethical leadership and rotational accountability. If even 2–5% of humanity fully lives out Namummaa, it may catalyze a profound shift: a tipping point toward a more ethical, peaceful, and creative human civilization.

Beyond Labels: Namummaa as movement for our time

Based on my development practice across civil society organizations (1991–2008), sustainable development is impossible without Namummaa—without the ethic of dignity, balance, and interdependence guiding collective efforts.

In today’s world, people are routinely reduced to categories: race, religion, nation, and ideology. These identifiers can hold meaning—but they must never replace or override our fundamental Namummaa. We reject a world where humans are alienated from one another, from themselves, and from nature. We call instead for a movement grounded in shared humanness, not shallow identities; in dignity, not division; in regeneration, not consumption.

Let every scientist, educator, policymaker, artist, parent, and leader ask: How does my work serve or diminish Namummaa? How can it be reframed to uplift our shared humanity?

From Betcho to Adama, from Haji Boru’s wisdom to scholars like Asmarom, Asefa, Bekalu, and Gerbi, the call of Namummaa is clear: humanness must be lived, not theorized. Michuu Namummaa is carrying this legacy forward.

Thus, Michuu Namummaa is not merely a framework. It is a call to recenter the human being within all our systems, to reclaim morality not as dogma but as a generative responsibility, and to live in a manner worthy of our highest human potential—while fostering societies in which all can flourish.

This is not a call for utopia; it is a call for balance. It is a call for courage and a call for each of us to become, in our own way, a beacon of Namummaa. AS

Editor’s Note: Berhanu Workneh Desta is the Founding Director of Michuu Namummaa Development Organization, an Ethiopian civil society organization dedicated to advancing shared humanity (Michuu Namummaa) as a framework for peace, justice, and sustainable development. He previously worked as a development practitioner (1991–2008) with both local and international civil society organizations and currently serves as a freelance consultant and trainer. Berhanu can be reached at berhanu.consult@gmail.com

Why is Oromo cultural awareness important?

Oromo cultural awareness is crucial for several interconnected reasons, spanning issues of human rights, historical justice, national cohesion, and global cultural diversity.

Here’s a breakdown of why it is so important:

1. For the Oromo People Themselves: Identity and Dignity

· Reclamation of Identity: For centuries, the Oromo people, the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, faced systemic marginalization, cultural suppression, and political exclusion under successive imperial and authoritarian regimes. Their language, history, and traditions were often sidelined or actively suppressed. Cultural awareness is a powerful act of reclaiming and celebrating a proud identity that was denied for so long.

· Preservation of Heritage: Oromo culture is rich with unique systems like the Gadaa system (a sophisticated indigenous democratic socio-political system recently inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity), the Qalluu spiritual tradition, the Irreechaa thanksgiving festival, and a vast oral literature. Awareness helps preserve these irreplaceable cultural treasures for future generations.

· Psychological Empowerment: Seeing one’s culture recognized, respected, and valued is fundamental to individual and collective self-esteem. It counters the negative effects of historical oppression and fosters a sense of pride and agency.

2. For Ethiopia: National Unity and Democratic Stability

· Addressing Historical Grievances: Ethiopia is a diverse nation of over 80 ethnic groups. A major source of political tension has been the historical dominance of a single cultural narrative while others were marginalized. Acknowledging and promoting Oromo cultural awareness is a critical step toward addressing these historical injustices and building a more equitable foundation for the country.

· Genuine Unity vs. Forced Assimilation: True national unity is not achieved by forcing everyone to assimilate into a single culture. Instead, it is built on mutual respect and the celebration of diversity. A Ethiopia that embraces the fullness of its Oromo, Amhara, Tigrayan, Somali, and other cultures is stronger and more resilient than one that suppresses them.

· The Gadaa as a Democratic Resource: The principles of the Gadaa system—including power rotation, periodic review of leaders, and inclusive assembly-based decision-making—offer valuable indigenous models for governance and conflict resolution that can inform Ethiopia’s modern democratic development.

3. For the Global Community: Knowledge and Diversity

· Contributing to Human Knowledge: Systems like Gadaa provide invaluable case studies for anthropologists, political scientists, and historians. They challenge Western-centric notions of where democracy and sophisticated governance originated, showing that such systems developed independently in different parts of the world.

· Enriching Global Cultural Heritage: The world is richer for its cultural diversity. The music, art, literature, and philosophies of the Oromo people represent a unique and important thread in the tapestry of human civilization. Losing such culture through assimilation or neglect would be a loss for all of humanity.

Key Context: What Increased Awareness Has Meant in Practice

In recent decades, increased Oromo cultural and political awareness has directly led to:

· The adoption of the Oromo language (Afaan Oromo) as an official working language of Ethiopia and its use in education and government.

· The public celebration of Irreechaa on a massive scale, both in Ethiopia and by the diaspora.

· Greater political representation and a central role in national politics.

· Academic studies and UNESCO recognition of the Gadaa system.

Conclusion

Oromo cultural awareness is not about promoting one culture above others. Rather, it is about correcting a historical imbalance, affirming the basic human right to cultural identity, and recognizing that a nation’s strength lies in embracing all of its constituent parts.

It is essential for:

· The Oromo people’s dignity and self-determination.

· Ethiopia’s attempt to build a just, stable, and truly unified state.

· The world’s understanding of human history and cultural diversity.

In short, it is a crucial step toward justice, peace, and a more complete understanding of our shared world.

From Shared Purpose to Genuine Solidarity: Moving Beyond Empty Unity

In Loving Memory of Kumsa Burayu, Devoted Advocate for Oromo Unity

Worku Burayu (Ph.D.)

Introduction

The passing of my younger brother, Kumsa Burayu, who gave his life to the cause of Oromo unity, has compelled me to write this article—both as a tribute to his memory and as a call to move beyond empty declarations of unity toward true solidarity. His lifelong devotion to the Oromo struggle was not grounded in slogans or fleeting alliances, but in an unshakable belief that our people can only be free through trust, sacrifice, and principled action.

Unity has long been invoked in the Oromo struggle for justice and self-determination. Yet too often, it has been reduced to rhetoric, fragile declarations that collapse under pressure, leaving our people vulnerable to division and betrayal. My baby brother, Kumsa Burayu, who recently passed away in his mid-fifties, saw this danger clearly. Throughout his life, he fought not for the shallow comfort of empty unity, but for the deeper, more demanding work of genuine solidarity. His commitment was not abstract. He lived it. Kumsa gave his time, his energy, and ultimately his life’s strength to ensure that Oromo unity was not a slogan but a living principle. He believed that real solidarity requires honesty, trust, and sacrifice—that it is built not on convenience or temporary alliances, but on an unshakable commitment to the collective good.

Superficial unity may rally a crowd, but it cannot sustain a movement. Only solidarity—rooted in truth and accountability—can carry us forward. Kumsa’s journey reminds us that the struggle for Oromo freedom and dignity cannot rest on half-hearted promises. It demands integrity, courage, and the willingness to put principle above personal gain.

This dedication is both personal and public. It honors the memory of Kumsa Burayu, whose heart never wavered, and it carries his message forward: that we must rise beyond empty unity and embrace genuine solidarity. Only then can we fulfill the vision of justice and self-determination for which he and countless others, gave everything.

Unity in Ethiopian Political History

The idea of unity has often been used and abused in Ethiopian political history. Regimes from Menelik to Haile Selassie, and later the Derg, weaponized unity to dominate, silence, and homogenize. Under slogans like “Ethiopia First,” the Derg vilified groups like the OLF and TPLF as threats to national unity. Even after the fall of the military regime, unity remained an ideological tool, sometimes used to marginalize dissent in the name of national cohesion. Ethnic federalism under the EPRDF shifted the conversation but did not resolve the underlying tensions.

Today, unity still risks becoming a hollow word, uttered in songs, rallies, and political speeches, but empty of shared meaning. The only way to move beyond that is to redefine unity as solidarity with justice. We must stop romanticizing unity as a fixed ideal and start building it as living practice.

The Use and Abuse of the Word Unity in Oromo Politics

The concept of unity has long served as a unifying call for the Oromo liberation movement. Freedom fighters, activists, politicians, civil society organizations, artists and religious leaders have consistently invoked it. For decades, appeals for unity have been a central theme in Oromo public life. They have been articulated at conferences devoted to liberty, equality, and democracy; voiced through speeches at political and cultural gatherings; expressed in the lyrics of Oromo musicians during festivals; and reiterated by keynote speakers across a wide range of forums. From the seminal addresses of the Mecha Tulama Association to the slogans advanced by Qeerroo and Qaarree youth movements, unity has consistently been framed as a sacred and non-negotiable principle. Indeed, it constituted a decisive force in the eventual dislodging of the TPLF-led EPRDF regime.

Yet in Oromo politics, the word “unity” has become both overused and misused. We have accepted unity as a panacea for all ills—political repression, social injustice, internal division—without interrogating what it truly means. Often, unity’s absence is blamed for failed movements, and we mistakenly equate unity with uniformity. But true unity does not demand ideological uniformity. It is the ability to come together with our differences intact, guided by a shared vision and purpose.

What Unity Really Means

In my views, unity means coming together around shared goals such as freedom, justice, and the protection of Oromo identity—despite differences in region, religion, or political affiliation. It reflects a commitment to the collective good over personal or group interests. True unity is rooted in the values of the Gadaa system, where dialogue, consensus, and mutual respect guide decision-making. It demands tolerance and a willingness to cooperate even when perspectives diverge. It embraces our differences as strengths while working together toward common goals. True unity is grounded in a clear sense of purpose and a collective commitment to that purpose. It is not measured by the absence of conflict but by the strength of collaboration in the face of complexity. In its most honest form, unity empowers communities, amplifies their voice, and ensures resilience in the face of adversity.

Unity only holds meaning when defined and acted upon. In political discourse, it manifests in two major ways:The first is unity among political fronts and movements. This form often fails when movements regard each other as threats rather than partners. The second is internal party cohesion. Here, unity is about presenting a united front to supporters, yet internal rifts frequently expose instability. Both are important, but neither can succeed without mutual respect and a clearly defined common cause.

What Unity Is Not

Unity is not conformity, nor is it the forced agreement on ideas, values, or goals. When everyone is expected to think and act the same, it stifles diversity and weakens the depth of experience and perspective that gives strength to a movement.

Unity is also not simply about being in the same place or forming coalitions— mere gatherings of people or coalitions or proximity alone does not create genuine connection. Real unity is an ongoing process of active engagement, honest struggle, and mutual support, all rooted in a common purpose.

Why Unity Remains a Constant Theme

Oromo history is marked by shared suffering and marginalization, which naturally fosters a longing for togetherness. The call for unity echoes not just through politics but also through cultural narratives. One childhood story, told and retold, illustrates this: a father gives each of his sons a stick to break—each break theirs easily. Then he gives them a bundle of sticks, and no one can break them. “Together,” he says, “no one can break you.” This story embodies the Oromo yearning for solidarity in the face of external threats.

Finding Common Ground and Commitment to the Common Cause

Despite tactical or even strategical differences, Oromo political movements share a commitment to self-governance, justice, and dignity. The question is whether they can align behind this shared vision. Different strategies, whether peaceful resistance or armed struggle—need not divide us if we agree on the destination. We need not think identical to work together; we need only commit to the same goal: self-governance, justice, and dignity.

Victory requires dedication from all sectors of Oromo society. We must reject divisions—regional, religious, or political that weaken our collective voice. Instead, we must protect our language, cultural institutions, and democratic values. Unity will not come from waiting but from committing ourselves fully to the task at hand. Only then can we claim ownership of our future.

Shared Identity and Struggle

The Oromo people are bound by more than just language or geography. Afaan Oromo serves as a powerful unifier, spoken across regions and religious lines. Oromo literature, cultural festivals like Irreecha, and foundations like the Gadaa system are the backbone of a collective identity that has survived despite systemic erasure. The oral tradition, Argaa-Dhageetti, continues to transmit values of equality and social harmony.

While the Oromo embrace diverse religious beliefs—Waaqeffannaa, Islam, and Christianity—they are united by a common worldview that emphasizes justice, community, and reverence for life. These shared spiritual and cultural values form the moral framework of the Oromo struggle.

Unity in Practice-Historical Continuity

From colonization to military rule, the Oromo have faced systematic marginalization. Land grabs, arbitrary arrests, cultural suppression, and political exclusion are not new.

The Oromo struggle for self-determination has been shaped by regional movements uniting diverse communities under shared aspirations. In Wollo-Raya, and Yejju, uprisings in the late 1920s and early 1930s resisted imperial taxation and central domination in unity. In 1936, the Western Oromo Confederation—comprising thirty-three leaders from western Oromia—petitioned the League of Nations for recognition under a British mandate, marking a significant early expression of Oromo unity Scribd. In Hararghe, the Arfaan Qallo movement, initiated in 1962, utilized music and literature to promote Oromo identity and resistance ResearchGate. Concurrently, the Bale Revolt (1963–1970) saw Oromo people unite against feudal oppression, laying the groundwork for modern Oromo nationalism.

Later, the Mecha-Tulama Self-Help Association (1963–1967) emerged as the first pan-Oromo movement, coordinating nationwide peaceful resistance and demonstrating the vitality of Oromo unity OPride.com. Together, these movements illustrate that Oromo unity was not merely an aspiration but a practical force—sustaining resistance, affirming identity, and paving the way for later organizations such as the Oromo Liberation Front. The Qeerroo and Qaarree movements, grassroots uprisings, and decades of resistance have forged a new generation that understands the value of unity not as submission, but as collective strength.

The Role of Oromo Women in Oromo Unity

Oromo women have been pivotal in fostering unity within their communities through cultural, social, and political engagement. Oromo women have long been central to the cohesion and resilience of their communities. They act as cultural guardians, preserving traditions, rituals, and oral histories that define Oromo identity. Through their participation in events like the Irreecha festival, women not only celebrate but also reinforce communal bonds and collective identity and a sense of shared heritage (Ethiopia Autonomous Media). Beyond culture, Oromo women make substantial economic contributions through farming, trade, and entrepreneurship, supporting families and local communities. Their economic involvement grants them influence in local decision-making and fosters unity by ensuring that community well-being is prioritized (allAfrica.com). Women in Oromo society also play key leadership roles, mediating disputes and promoting unity and peace within families and communities.

Traditional institutions such as Siinqee empower women to uphold social justice and protect the rights of the vulnerable, creating inclusive and harmonious communities. Oromo women have been at the forefront of political movements, advocating for the rights of their people and challenging oppressive systems. They have organized protests, participated in negotiations, and represented the Oromo cause on national and international platforms, demonstrating resilience and commitment to justice (Advocacy for Oromia). Their involvement demonstrates both courage and a commitment to justice, ensuring that the collective voice of the Oromo people is heard at local, national, and international levels (press.et).

The unity of the Oromo people, reinforced by the active participation of women, has had profound implications for regional politics in East Africa. In essence, the active participation of Oromo women ensures that unity within the community is not merely symbolic. Their leadership, activism, and cultural stewardship strengthen social cohesion and amplify the political influence of the Oromo people. Together, the cultural, social, and political unity of the Oromo community represents a powerful and transformative force in regional politics, demonstrating how grassroots cohesion can drive meaningful change at broader societal and governmental levels. The active participation and leadership of Oromo women in various spheres underscore their integral role in fostering unity and resilience within their communities.

From Purpose to Power

The future of Oromo unity lies not in speeches or slogans, but in purpose-driven solidarity. We must recognize our shared struggle, uphold our diverse identities, and commit to the common cause of freedom, democracy, and dignity. True unity requires that we stand together—not because we are the same, but because we believe in something greater than ourselves. Only then will we move from shared purpose to genuine solidarity.

The Power of Action

Unity must go beyond rhetoric. Each of us can contribute. In personal spaces, we must challenge divisive narratives and foster dialogue. In communities, we must mobilize, speak out, and support those marginalized. In our economic lives, we must back businesses and initiatives aligned with our values. And with our time, we must volunteer, organize, and participate in the building of a just society.

Closing Reflection:

The struggle for Oromo freedom and dignity cannot be carried by empty words or fragile alliances. It requires honesty, sacrifice, and the courage to place principle above personal gain. My late brother, Kumsa Burayu, lived and transitioned with this conviction. His legacy is a reminder that genuine solidarity is not an option but a necessity if our people are to secure justice and self-determination. To honor his memory, we must rise beyond the comfort of shallow unity and embrace the demanding but enduring strength of true solidarity.

About the Author: Dr. Worku Burayu is an Agronomist by profession; Steward of the Oromo causes by purpose. He is a committed advocate for justice, pluralism, and sustainable development in Oromia and beyond.

References

- A cultural representation of women in the Oromo society

- Advocacy for Oromia

- allAfrica.com

- Ethiopia: Vital Role of Women Among the Oromo People

Gadaa: An Indigenous Democracy of Oromo people on Promoting …

- Nordic Journal of African Studies

- Role of Oromo Women in Oromia’s Struggle for Freedom

Historic Achievement: Waaqeffannaa to Be Taught in Norwegian Secondary Schools

Bergen, Norway – In a landmark step for religious and cultural recognition, Waaqeffannaa, the indigenous faith of the Oromo people, has been officially included in Norway’s secondary school as part of religion and society education in school curriculum. This groundbreaking decision marks the first time Waaqeffannaa will be taught as part of the Religion and Society course, affirming its place among the world’s major religions.

Starting next week, students in Bergen will learn about Waaqeffannaa as a distinct and structured belief system. The Oromo community, both in Norway and worldwide, has welcomed this initiative with great pride, seeing it as long-overdue recognition of their spiritual heritage.

Waaqeffannaa is one of the oldest continuous religious traditions in the world, with a history spanning over 6,000 years. It is grounded in the worship of one God, Waaqa Tokkicha, and emphasizes values such as moral integrity (Safuu), peace (Nagaa), environmental stewardship, and social equality. Its teachings are conveyed through the Oromo language, enriching its cultural and linguistic significance.

This inclusion is the result of dedicated advocacy by community leaders and scholars who have worked tirelessly to document and promote Waaqeffannaa’s philosophy and practices. Their efforts ensure that both Oromo and non-Oromo students can now learn about a faith that champions harmony with nature and equality among people.

The introduction of Waaqeffannaa into formal education is more than an academic update—it is a celebration of identity and resilience. It offers a meaningful opportunity to elevate awareness of Oromo culture and history on a global stage.

As one community leader expressed, “This is only the beginning. We encourage all followers of Waaqeffannaa to take pride in this achievement and continue sharing the beauty and wisdom of our faith.”

This inspiring development opens new pathways for intercultural dialogue and understanding, reminding us of the rich diversity of human belief and the importance of honoring indigenous wisdom.

Celebrating Irreechaa: A Tradition of Gratitude

Long, long ago, nestled in the heart of Oromia, lived a wise old man named Oro. Every year, as the rainy season bid farewell and the land burst into vibrant green, Oro would climb atop the highest mountain. He would raise his hands to the sky and offer a heartfelt “Galatoomi Waaqaa!” – “Thank you, Waaqaa!” to the creator, for the blessings of rain, harvest, and life.

Oro’s gratitude became a tradition. His children, and their children after them, followed his example. They would gather by rivers and lakes, adorned in beautiful traditional clothes, singing songs of praise and offering gifts of flowers and fresh crops. This joyous celebration became known as Irreechaa – a time for thanksgiving, unity, and hope.

As generations passed, the Oromo people spread across the land, but they never forgot Oro’s tradition. Every September, they would journey to sacred places, especially to Finfinne, their capital city. There, by the shimmering waters, they would come together, a sea of colorful garments, to sing, dance, and offer their gratitude to Waaqaa.

Children would toss flowers into the water, their laughter echoing through the air. Elders would share stories of Oro and the importance of thankfulness. And as the sun set, painting the sky in hues of black, red and white, the Oromo people would feel a deep sense of connection to their history, their culture, and their God.

The end.

Daaniyaa: A Journey Through Oromo Spirituality and Culture

For generations, the wisdom of Waaqeffannaa—the ancient, monotheistic faith of the Oromo people—has been carried in the hearts and oral traditions of its adherents. Today, that wisdom finds its foundational voice in Daaniyaa.

This sacred text is a vital link to a spiritual heritage rooted in the reverence of Waaqayyo (the Supreme Creator), harmony with nature, and the moral principles of Safuu (moral and ethical order). It is an invitation to explore:

· Theological Depth: Understand the core principles of Waaqeffannaa, its view of the Creator, and the intricate relationship between humanity, the natural world, and the divine.

· Cultural Reclamation: Engage with a text that reaffirms a rich cultural identity, offering a powerful counter-narrative to historical erasure and a path for cultural preservation.

· Universal Spiritual Insights: Discover timeless teachings on peace, environmental stewardship, and community that resonate with global seekers of truth.

Daaniyaa is essential reading for the Oromo youth connecting with their roots, for elders preserving their legacy, for scholars documenting indigenous knowledge, and for anyone drawn to profound and authentic spiritual systems.

This is more than a publication; it is an act of preservation. Own a piece of living history. Discover the spiritual foundation of a nation.

Daaniyaa refers to the foundational written sacred text of Waaqeffannaa, the indigenous religion of the Oromo people. It serves to preserve Oromo culture and spirituality by documenting core beliefs in Waaqa Tokkicha (One God), moral principles like safuu (spiritual balance), and ancestral connections (Ayyaana). The text is crucial for religious identity, education, and promoting the Oromo language and heritage.

Celebrating Shanan: A Mother’s Festival in Oromo Culture

It is a special day for Sena Boka. Most of all, it is the day she had her first child, and for this she traditionally thanked God for helping her with members of the Oromo community mainly women who loved and respect Sena. She celebrated the Shanan with her friends in traditional Oromo beauty. The main purpose of Shanan is to encourage and bless the woman who gave birth on the fifth day. It is also a mother’s festival and a thanksgiving to God for helping her to give birth in peace. This is the day they celebrate the Shanan Day.

The rituals performed on this cultural ceremony have many benefits for the mother who has just recovered from childbirth. However, what is the essence of Shanan in Oromo culture? What are the benefits of this ceremony? What is done on this day? In this article we will try to look at the Shanan nature of things.

In Oromo culture, the shanan day (the fifth day after childbirth) is a deeply respected and cherished tradition. This day holds significant cultural, social, and emotional importance for the mother, the newborn, the family, and the community. It is a time of celebration, healing, and bonding, rooted in the values of care, support, and communal love.

The Shanan is an important and celebrated part of the midwife’s life. This is to the advantage of the family that a woman is safely released after carrying it in her womb for nine months. And the newborn is an addition to the family. Therefore, they do not leave a woman alone until she becomes stronger and self-reliant. Because it is said that the pit opens its mouth and waits for her. And when she goes to the bathroom, she carries an iron in her hand, and sucks it into her head.

This system plays an important role in helping the mother recover from labor pains. Family and friends who attend the Shanan will also encourage the midwife to look beautiful and earn the honor of midwifery. On this Shanan they made the midwife physically strong, socially beautiful, gracefully bright, and accustomed to the burdens of pregnancy and childbirth.

Why the Shanan Day? In the Oromo worldview, the number five holds special importance. The Gadaa system is organized around cycles of fives and multiples of five (e.g., five Gadaa grades, eight-year terms consisting of 5+3 years). Waiting for five days is a way to honor this cultural structure and to properly prepare for the important act of naming.

Key Aspects of Shanan:

Community Support:

The core of the Shanan tradition is the communal nature of Oromo society, where the well-being of the mother and child is a shared responsibility.

Blessings and Encouragement:

Community members gather to provide emotional support, motivation, and blessings to the mother, helping her regain strength and feel connected.

Marqaa Food:

The traditional food served on this day is marqaa. The serving of marqaa, a traditional food, is a central part of the celebration, symbolizing the care, blessings, and communal solidarity being extended to the new family. The midwives washed their genitals and ate together. Traditional songs of praise to God and encouragement of the mother are sung in turn.

Cultural Identity:

The ritual reinforces Oromo cultural identity and continuity, serving as a way to preserve and pass down these traditions to younger generations. During the ceremony, mothers dressed in traditional clothes surrounded the mother and expressed their happiness; sitting around the midwife after eating the marqaa, they blessed the new mother, ‘give birth again; carry it on your shoulder and back; be strong in your knees.’

Strengthening Bonds:

Shanan strengthens social and emotional bonds within the community, as everyone participates in welcoming the new member.

The celebration of the Shanan (fifth day) after a birth is a deeply significant and cherished ritual in Oromo culture, rooted in the Gadaa system. This culture has been weakened for centuries by various religious factors and the influence of foreign regimes. However, with the struggle of the Oromo people, the culture of encouraging childbirth is being revived and growing. Of course, many things may not be as perfect as they used to be. There is no doubt that the honor of Shanan as Sena Boka will contribute to the restoration of Shanan culture.