Oromos — cast as foreign, aliens to their own lands, have been the targets of the entire infrastructure of the Ethiopian state since their violent incorporation. Our identity, primarily language, religion and belief systems and cultural heritage have been the main targets of wanton destruction.

Oromo and its personhood were already demonized, characterized as embodiments of all that is inferior, shameful and subhuman from the beginning. Oromo people were economically and politically exploited, dominated and alienated.

Oromo cultural, political and religious institutions have been under massive attacks and dismantlement by consecutive Ethiopian governments. Oromos were rendered slaves on their own lands by a colonial land tenure system.

Given the huge systematic and structural forces that have been mobilized against Oromo people and its peoplehood, it is truly astonishing that we have survived. But we have survived not by some miracle, but because our ancestors have continuously resisted violent assimilation, dehumanization, economic exploitation, and complete eradication.

We have survived because our people have courageously and wisely Organized, sang, fought and sacrificed. We have survived because of brilliantly organized Oromo institutions such as Macha Tulama, which have held our communities together.

For five decades, this organization has been the vanguard of the Oromo people’s struggle for freedom, liberty and autonomy. Macha Tulama was conceived at a time when Oromo people desperately needed institutions that would provide direction, leadership, and mobilize the financial, human, intellectual and creative resources to empower Oromo communities.

At the time of its founding, the association was confronted with dire economic, social and political predicaments the Oromo were facing. One of the most important tasks of this organization has been rebuilding the confidence and trust of Oromo people in their own cultural heritage, language, belief systems and identity.

Creating opportunities and spaces for a people who have been historically denigrated and traumatized to regain their self-esteem was and is no easy task. This is a project we must continue, until Oromos are able to have complete control over their fate and future.

There was nothing easy about being Oromo and being young 50 years ago. Young people, students and others, risked their lives, limbs and property to organize, to publish leaflets and other literature that would become vital sources of national consciousness raising and empowerment. Macha Tulama leaders, members and others affiliated with the organization-faced torture, death, imprisonment, excruciating pain, and harassment.

Every gain that has been made by this association has been because of the huge sacrifices paid by individuals and by the collectives to which they belonged. We are here today celebrating the 50thanniversary of this association’s founding because of the sacrifices made, and most importantly, because of the vision of the leaders and members of Macha Tulama — a vision that one-day Oromos can live with dignity and freely on their own lands.

Macha Tulama has been an inspiration as a symbol of unity, national consciousness, wisdom and strength in leadership and has provided us with a new and rich understanding of the power of inclusive pan Oromo movements.

Surely, much has changed since it’s founding, but not so much so that Maaca Tulema has become irrelevant to Oromos living today. Macha Tulama’s vision — of promoting, empowering and liberating Oromo people remains as relevant today as it was when it was founded.

The Ethiopian socio- political establishments, who have always opposed and mercilessly attacked any pan-Oromo movements, have not changed very much in nature. This is why we are here today commemorating the 50th anniversary of Macha Tulama outside of Oromia, rather than on our lands, Oromia.

The work began by Macha Tulama must continue. It is critical that we continue to build inclusive pan-Oromo movements and institutions that empower our people for self-rule. My generation should look into the history of the Macha Tulama Association. They will find themselves moved by the vision, mission, courage, ingenuity and principle of the leaders and members of this organization.

We must ask ourselves how these brilliant and innovative groups of people were able to accomplish the impossible during one of the darkest periods of Oromo history. What techniques, methods and leadership styles did they employ to build a pan-Oromo organization at a time when using the word Oromo itself was a crime?

We must closely study the life, achievements and challenges of giant individuals such as Alemu Kittessa, Haile Mariam Gamada, Haji Robale Ture, General Taddesse Birru, Astede Habte Mariam and so many others. I am endlessly inspired and encouraged by the stories of these great Oromo leaders.

There is a lot for us to learn about how to organize in a way that dignifies and solidifies people’s bond, ways that create a real sense of community, and a sense of cohesiveness that is based on recognition of diversities as well as the commonalities that bind us.

We are here today because of the sacrifices made by thousands of Oromos, in every corner of Oromia. Most of their stories have not been told—the stories of ordinary people who have resisted century old colonial domination, exploitation, and assimilation.

Our elders have been so preoccupied with the task of surviving and with the task of laying the ground upon which we can hold our heads high and walk. It is this we must remember as we go about the tasks of organizing, documenting, painting, writing and creating institutions to build our communities’ capacity for the next fifty years and beyond.

We must learn from the founders of this association that quality of leadership, vision, principle, innovation and good faith in leadership are necessities for our continued survival as a people. I would like to end with an excerpt from a quote from one of my favorite African American thinkers and writers. Audre Lorde calls it a litany for survival

For those of us who live at the shoreline

standing upon the constant edges of decision

crucial and alone

looking inward and outward

at once before and after

seeking a now that can breed

futures like bread in our children’s mouths

so their dreams will not reflect

the death of ours:

For those of us

who were imprinted with fear

like a faint line in the center of our foreheads

learning to be afraid with our mother’s milk

for by this weapon

this illusion of some safety to be found

the heavy-footed hoped to silence us

For all of us

this instant and this triumph

We were never meant to survive

And when the sun rises we are afraid

it might not remain

when the sun sets we are afraid

it might not rise in the morning

and when we speak we are afraid

our words will not be heard

nor welcomed

but when we are silent

We are still afraid

So it is better to speak

Remembering

We were never meant to survive

*Ayantu Tibeso is a researcher and communications consultant based in North America. She can be reached at atibeso@gmail.com or on twitter @diasporiclife.

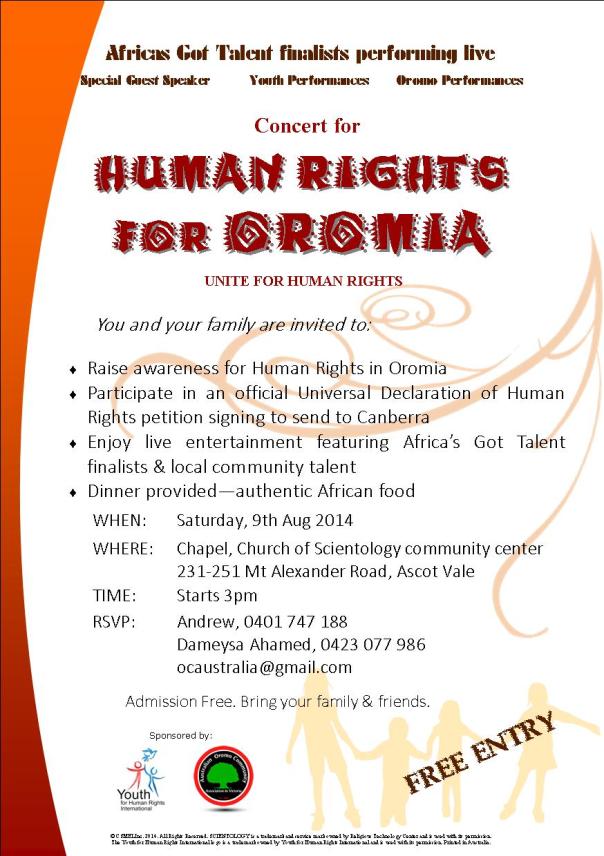

Melbourne’s diverse communities came out to support the Oromo people’s struggle for human rights, and oppose the ongoing human rights violations against Oromo students and civilians by the Ethiopian TPLF regime.

Melbourne’s diverse communities came out to support the Oromo people’s struggle for human rights, and oppose the ongoing human rights violations against Oromo students and civilians by the Ethiopian TPLF regime.

According to the concluding remarks of researcher Denebo Dekeba, the current government of Ethiopia has committed despicable crimes against humanity including genocide; arbitrary arrest, torture ,and other inhuman or degrading treatment of people ; economic exclusions and discriminations ; land grabbing and eviction from land; violation of freedom of thought and expression of opinion.

According to the concluding remarks of researcher Denebo Dekeba, the current government of Ethiopia has committed despicable crimes against humanity including genocide; arbitrary arrest, torture ,and other inhuman or degrading treatment of people ; economic exclusions and discriminations ; land grabbing and eviction from land; violation of freedom of thought and expression of opinion.