Category Archives: News

Tajoo Roobaa: Sacred Rituals for Rain and Peace in Oromia

“Tajoo Roobaa”: The Arsii Oromo’s Sacred Invocation for Rain, Peace, and Prosperity

Sub-headline: At Hara Dambal in Malka Utaa Waayyuu, ancient rituals connect community to Waaqa (God) and mark a new year under the Amajjii moon.

By Maatii Sabaa, Hara Dambal, Arsi Zone, Oromia – Under the bright Amajjii moon, the rolling hills of Hara Dambal echoed this week not just with the wind, but with the collective prayers of thousands. The Arsii Oromo people of Sikkoo Mando, Utaa Waayyuu, gathered to celebrate the profound and spiritually charged festival of Irreecha Tajoo Roobaa—a sacred ceremony dedicated to invoking rain, giving thanks to the creator, and ushering in a new year.

More than a cultural event, Tajoo Roobaa is a deep-rooted indigenous system of supplication to Waaqa (God) for rain. The ceremony, observed specifically during the Amajjii lunar month, serves a dual purpose: as a thanksgiving to the divine (Hinikkaa) and as the celebration of the Oromo New Year.

The rituals follow a powerful annual cycle. Days before the main gathering, the community embarked on a spiritual journey, traveling from their homes to the sacred site of Araddaa Jilaa near the Haroo Booramoo (Lake Booramoo). There, initial prayers for rain were offered. This preparatory pilgrimage culminated in the major congregation at Hara Dambal, where the main Ayyaana Tajoo Roobaa was enacted with diverse and symbolic rituals.

Chants filled the air, carrying the community’s unified hopes skyward. The core of their invocation is a timeless appeal to the divine for balance and blessing: “Bona nuuf gabaabsi” (Shorten the dry season for us), “Badheessa nuu deebisi” (Bring us abundance), “Ganna nuuf dheereessii” (Prolong the rainy season for us), and “Nagaa nuuf buusi” (Bestow peace upon us).

Elders, clad in traditional dress and holding freshly cut grass and flowers—symbols of fertility and peace—led the prayers. The gathering was a vibrant tapestry of song, dance, and solemn prayer, embodying the Arsii Oromo’s intimate connection with their environment, their cyclical calendar, and their spiritual heritage.

“This is not just a festival; it is our covenant with nature and Waaqa,” explained one elder, who chose to be identified simply as Abbaa Gadaa. “When we stand here at Hara Dambal, we are speaking to our creator with one voice, asking for the sustenance of life—rain—and for peace to govern our lives. Celebrating it in Amajjii marks our new beginning.”

The Irreecha Tajoo Roobaa at Hara Dambal stands as a powerful testament to the resilience of indigenous Oromo spiritual practices. It is a living tradition where cosmology, environmental stewardship, and social cohesion intertwine, ensuring that the sacred plea for a fruitful and peaceful year continues to resonate from generation to generation.

Exploring Western Oromo History: New Book Launch

Landmark Book Launch Sheds Light on Western Oromo History

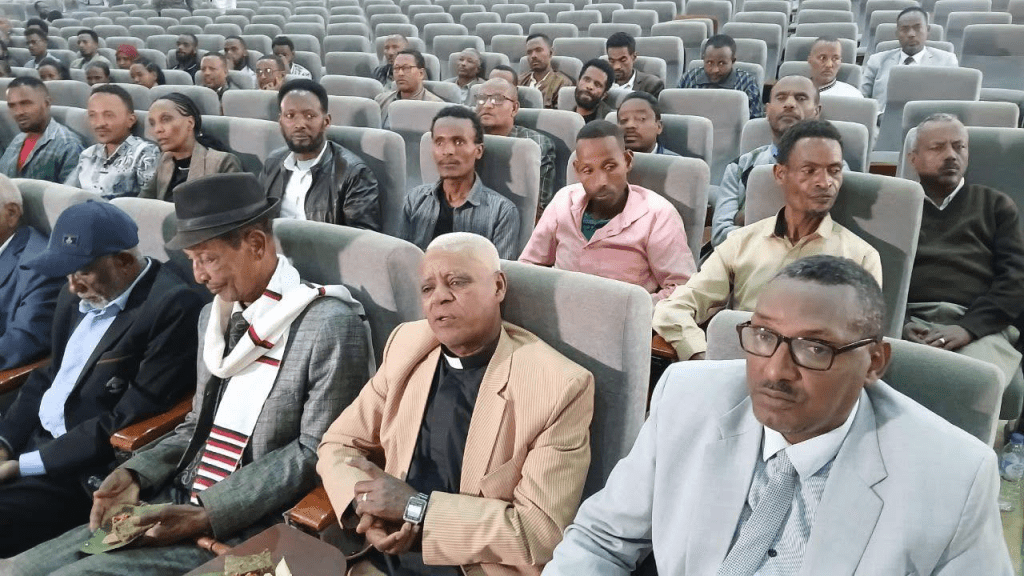

Finfinnee, January 24, 2026 – A significant contribution to Ethiopian historiography was celebrated this week with the official launch of the book “The Western Oromo and The Ethiopian State to 1941.” The work, authored by renowned historian and scholar Professor Tesema Ta’a, was launched at a formal ceremony held at Wollega University.

The book, published in English by Wollega University Press, offers a comprehensive and detailed examination of the political and social history of the Western Oromo people within the context of the Ethiopian state, tracing pivotal developments up to the year 1941. This period marks a critical juncture in modern Ethiopian history, and Professor Tesema’s research provides an essential perspective from the Oromo community’s experience.

The launch event was attended by a distinguished gathering of historians and scholars from various Ethiopian universities, underscoring the academic importance of this publication. The ceremony featured remarks that highlighted the book’s role in enriching the understanding of Ethiopia’s complex and multifaceted historical narrative.

A Deeper Scholarly Contribution

Professor Tesema Ta’a’s work is heralded as a meticulous academic study that draws on extensive research. It moves beyond broad national narratives to focus specifically on the institutions, interactions, and experiences of the Western Oromo. Scholars present at the event noted that such focused studies are crucial for building a more complete and inclusive historical record.

Significance and Impact

The launch of “The Western Oromo and The Ethiopian State to 1941” represents more than just the publication of a new academic text. It signifies a growing emphasis within Ethiopian academia on exploring and documenting the diverse regional and ethnic histories that comprise the nation’s past. By bringing this research to the forefront, Wollega University and Professor Tesema have provided an invaluable resource for students, researchers, and anyone seeking a deeper understanding of Oromo history and state-society relations in Ethiopia.

The book is now available through Wollega University Press.

About the Author: Professor Tesema Ta’a is a respected figure in the field of Ethiopian history, known for his dedicated research and scholarly contributions focused on Oromo history and the broader Horn of Africa region.

Media Contact: Dhaba Fiqadu

Oromo Scientist Launches School in Oolankomii: A Legacy of Education

A Mother’s Name, A Nation’s Future: World-Renowned Oromo Scientist Inaugurates School in Oolankomii

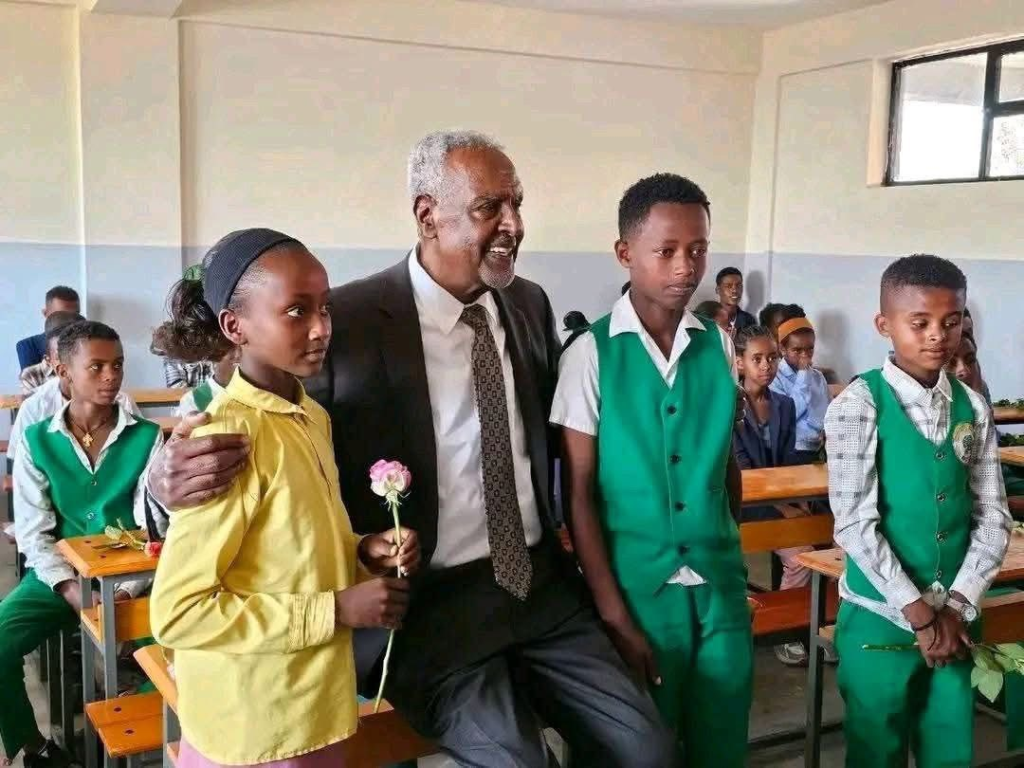

OOLANKOMII, Shaggar Lixaa – In a powerful gesture of giving back, world-renowned Oromo scientist Professor Gabbisaa Ejjetaa today inaugurated a secondary school he personally funded and built in his hometown of Oolankomii. The school was officially opened for service on Amajjii 25, 2026.

Named in honor of his late mother, Mootuu Ayyaanoo, the “Mootuu Ayyaanoo Secondary School” stands as a permanent tribute to the values of nurture, wisdom, and foundational support—embodied by mothers in Oromo culture. Professor Ejjetaa stated that naming the institution after his mother was a way to immortalize her sacrifices and to inspire future generations to honor their roots while reaching for the stars.

The inauguration ceremony was a moment of immense pride and celebration for the community of Oolankom. Local elders, educators, students, and residents gathered to witness the ribbon-cutting, marking the culmination of Professor Ejjetaa’s vision to provide a modern, quality educational facility for the town’s youth.

Professor Gabbisaa Ejjetaa, a distinguished plant geneticist known for his groundbreaking work in developing drought-resistant sorghum, is a source of immense pride for the Oromo people globally. The establishment of this school underscores his deep commitment to translating global scientific acclaim into tangible local development. It represents a different kind of freedom fight—the liberation of young minds through education.

The Mootuu Ayyaanoo Secondary School is equipped to serve hundreds of students, offering a conducive learning environment designed to foster academic excellence and critical thinking. Community leaders hailed the project as transformative. “This is not just a building; it is a beacon of hope,” said one elder present. “Our son excelled abroad, but his heart remained here. Today, he plants the seed of knowledge for our children. Ulfaadhaa—may it bear abundant fruit.”

The school’s opening is seen as a significant milestone for educational access in the region, promising to empower a new generation of Oromo youth by combining rigorous academics with a strong grounding in their cultural identity and values.

In his address, Professor Ejjetaa emphasized that true development begins with education. He expressed his hope that the school would become a cradle for future scientists, leaders, and compassionate citizens who would contribute to their community and the world.

The inauguration of the Mootuu Ayyaanoo Secondary School is more than a local event; it is a resonant story of global success circling back to its source, of a scientist honoring his first teacher—his mother—and of a community’s future being brightly rewritten.

Ulfaadhaa jennaan. ![]() (We say, may it bear fruit.)

(We say, may it bear fruit.)

The Voice That Sowed a Revolution – Daagim Mokonnin and the Soundtrack of Oromo Awakening

Feature Commentary: The Voice That Sowed a Revolution – Daagim Mokonnin and the Soundtrack of Oromo Awakening

The story of Daagim Mokonnin is not merely a biography of an artist; it is a chronicle of a people’s reawakening, told through melody, struggle, and an unbreakable spirit. Known affectionately by his stage name “Kiilolee” (The Melody), Daagim’s journey from a child chastised for his language to a foundational pillar of modern Oromo music encapsulates the political and cultural resurgence of the Oromo nation in the late 20th century.

His art was never just entertainment. In an era where speaking Afaan Oromoo in the capital, Finfinnee (Addis Ababa), was an act of defiance met with scorn or worse, Daagim’s music became a vessel for identity. “When we sang, it wasn’t just for money,” he recalls. “It was about contributing to the growth of the Oromo language and making the Oromo proud of their tongue.” His first hit, “Agadaa Birraa”, was more than a love song; it was a cultural declaration. Using the metaphor of the Oromo agadaa (a traditional stool) and the spring season of Birraa, it wove romance with deep cultural pride, instantly resonating with a generation hungry for such representation.

His path was forged in adversity. Arriving in Finfinnee as a boy from Wallagga, he was thrust into an educational system designed to erase his identity. “I didn’t know a word of Amharic, only Oromiffa,” he says. The punishment was isolation and ridicule—a “qophaa” (nickname) of shame that marked him as an outsider. Yet, this very oppression became the fuel for his mission. He and a small band of pioneering artists, operating under the banner of the Oromo Liberation Front’s cultural wing, became architects of resistance. They staged Oromo-language radio dramas, walked miles to recording spots, and produced music with rudimentary instruments, all under the watchful eye of a hostile state.

The collective he was part of—artists like Eebbisaa Addunyaa, Jireenyaa Ayyaanaa, and Usmaayyoo Muusaa—did not just sing; they curated a movement. Their style, from Daagim’s iconic headscarf and afro to their distinct aesthetic, was a deliberate, fashionable rejection of assimilation. “There was no borrowed ‘style’,” he insists. “Wearing a scarf is Oromo. If you go to rural Tulama, everyone wears it.” They were building a modern Oromo aesthetic from the ground up.

This courage came at a terrible cost. The 1990s, a period of cautious hope after the fall of the Derg, turned into a nightmare under the new regime. His comrades were hunted. His own brother was killed, and Daagim himself narrowly escaped assassination, an event that inspired one of his most poignant, unpublished poems of grief. Forced into exile in the United States for his safety, he continued his work, but the vibrant, collective creative ecosystem of Finfinnee was lost, replaced by the fragmented life of a diaspora artist.

Today, Daagim Mokonnin has stepped away from the secular music world, finding solace in Christianity. Yet, to view this as a retreat from his life’s work is to misunderstand the man. His legacy is cemented. He was present at the creation, one of the first to plant the seed of contemporary Oromo music—a seed that has now grown into a forest.

When he sings today, it is in praise of his faith. But the thousands who still play “Agadaa Birraa”, the artists who now fill stadiums singing in Afaan Oromoo, and the very fact that the language flourishes in the media, stand as living testimony to his earlier battle. Daagim and his generation were the bridge. They took the immense risk, endured the kutannoo (persecution), and used their art to make it normal, beautiful, and powerful to be Oromo in spaces designed to deny that reality.

His story is a powerful reminder that cultural work is not ancillary to political struggle; it is its bedrock. Before protests could rally millions, songs had to rally hearts. Before a language could be official, it had to be heard as worthy of a love song. Daagim Mokonnin, Kiilolee, provided that crucial, beautiful sound. He didn’t just sing melodies; he helped an entire generation find its voice.

U.S. Withdrawal from WHO: Impacts on Global Health Cooperation

WORLD NEWS: U.S. Announces Withdrawal from World Health Organization; WHO Expresses “Regret,” Defends Pandemic Record

GENEVA, January 24, 2026 – In a move that marks a seismic shift in the global health landscape, the World Health Organization (WHO) has confirmed receipt of a formal notification from the United States of America to withdraw from the UN health agency. The announcement, made public in a detailed statement from WHO headquarters today, has triggered widespread concern about the future of international cooperation against pandemics and other health threats.

The WHO statement began by acknowledging the United States’ historic role as a founding member, crediting its contributions to landmark achievements like the eradication of smallpox and the fight against HIV, polio, and Ebola. However, the tone swiftly turned to one of profound disappointment and warning.

“WHO therefore regrets the United States’ notification of withdrawal from WHO – a decision that makes both the United States and the world less safe,” the agency stated unequivocally.

The U.S. decision, which will be formally deliberated by the WHO Executive Board in February and the World Health Assembly in May 2026, was reportedly accompanied by sharp criticism from Washington. WHO noted U.S. claims that the agency had “trashed and tarnished” it, compromised its independence, and pursued a “politicized, bureaucratic agenda driven by nations hostile to American interests.” WHO rejected these assertions, stating, “The reverse is true,” and affirmed its commitment to engaging all member states with respect for their sovereignty.

Pandemic Response at the Heart of the Dispute

A central pillar of the U.S. justification, according to the WHO, was cited “failures during the COVID-19 pandemic,” including alleged obstruction of information sharing. In an extensive point-by-point rebuttal, the WHO defended its early pandemic actions, providing a detailed timeline:

- Dec. 31, 2019: WHO activated its emergency system upon first reports from Wuhan.

- Jan. 11, 2020: Before China reported its first death, WHO had already issued global alerts and guidance.

- Jan. 30, 2020: WHO declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC)—its highest alarm—when there were fewer than 100 cases and no deaths reported outside China.

The statement emphasized that while WHO recommended protective measures like masks and vaccines, it “at no stage recommended mask mandates, vaccine mandates or lockdowns,” asserting that final decisions rested with sovereign governments.

A Future Without U.S. Membership

The withdrawal comes at a critical juncture. WHO highlighted that its 194 member states last year adopted a landmark WHO Pandemic Agreement, designed to strengthen global defenses against future outbreaks. Nations are currently negotiating a complementary Pathogen Access and Benefit Sharing system to ensure equitable access to vaccines and treatments.

The U.S. exit casts a long shadow over these initiatives and the operational capacity of WHO, which has long relied on American financial and technical support. The agency, however, expressed hope for a future return.

“We hope that in the future, the United States will return to active participation in WHO,” the statement concluded, reaffirming its commitment to its constitutional mandate of pursuing “the highest attainable standard of health as a fundamental right for all people.”

The formal departure process is now underway, setting the stage for intense diplomatic discussions in the coming months over the architecture of global health security in an era of renewed great-power fragmentation.

Unlocking Oromo Women’s Power for Community Change

Feature Commentary: Beyond the Token – The Imperative of Unleashing Oromo Women’s Power

A profound truth is being spoken by the Oromo Sisterhood Institute, one that every Oromo civic and political organization must hear: the future of the Oromo people is held in the untapped potential of its women. The call is not for polite inclusion but for a fundamental restructuring of power.

The statement, “Advancing Equity for Oromo Women,” begins with a diagnosis that rejects all euphemisms. The absence of Oromo women from leadership boards, high-stakes negotiations, and strategic decision-making is not an “oversight.” It is, in their own powerful words, a “systemic breakdown.” This framing is crucial. It moves the conversation from a plea for a seat at the table to a demand to rebuild the table itself. The failure is not of individuals but of design.

The Mirage of Inclusion and the Reality of Exclusion

For too long, the solution offered to this systemic failure has been tokenism. A single female face on a committee of twelve becomes the shield against criticism, the hollow symbol of “inclusion.” The Oromo Sisterhood Institute rightly declares this era over. A committee with one woman is not inclusive; it is a perpetuation of the exclusionary structure. True engagement, they argue, requires “clear avenues for Oromo women to lead, impact, and mold our institutions.” This is the difference between being a guest in a house you did not build and being an architect of the new foundation.

The distinction between where Oromo women are currently concentrated and where they are systematically excluded is stark. They are overwhelmingly present in the volunteer work, the community mobilizing, and the front-line advocacy—the vital, often thankless labor that keeps movements alive. Yet, when the discussions shift to strategy, governance, and final decision-making—where the power to set direction and allocate resources resides—their voices fade into the background. The Institute’s message is clear: this dissonance is unacceptable. The work of the hands must be connected to the authority of the voice.

Dismantling the Barriers: A Matter of Justice

To move forward requires honest confrontation with the specific barriers. The Institute names them plainly: the gatekeeping of old networks, cultural norms that invisibilize women’s intellectual and leadership capacities, biased practices in hiring and promotion, and the simple, stark lack of representation where it counts most. These are not peripheral “women’s issues.” They are, as stated, core “issues of justice.” A struggle for liberation that internally replicates structures of oppression is a contradiction in terms.

An inclusive Oromo community, therefore, is not one that merely allows women to speak. It is one that actively “prioritizes women’s voices,” expects their leadership as a norm, and, most importantly, ensures that young Oromo girls can look at every level of their community’s power structure and see a reflection of themselves. Representation is not a gift; it is a mirror that tells the next generation what is possible.

The Unlocked Future

The concluding statement lands with the force of prophecy: “The future of the Oromo people depends on the power we choose to unlock in our women today.” This is the ultimate calculus. The Oromo struggle, in its quest for justice, self-determination, and cultural renaissance, cannot afford to operate at half-strength. It cannot hope to build a liberated tomorrow while silencing half its wisdom, courage, and vision today.

The Oromo Sisterhood Institute has issued more than a statement; it has issued a challenge. The transformation they speak of is not just for women—it is for the entire Oromo nation. To ignore this call is not just to fail women; it is to willfully constrain the future. When Oromo women are truly unleashed to lead, the very horizon of what is possible for the Oromo people expands. Their full potential is not a separate cause; it is the key to a transformed tomorrow.

Oromia’s Jila Tajoo: A Cultural Celebration of Unity

Feature News: Reviving Tradition – Oromia Calls for a Collective Celebration of Jila Tajoo/Birboo

Malkaa Baatuu, Oromia Region – The call has been sounded across Oromia. In a vibrant celebration of faith, culture, and community, the annual Jila Tajoo/Birboo is set to be observed with reverence and unity. The gathering, deeply rooted in the sacred Utaa-Waayyu tradition, has been officially announced for Sunday, January 25, 2026 or Amajjii 17, 2018 EC (Ethiopian Calendar).

The ritual, which holds both spiritual and social significance, will be held at Malkaa Baatuu, near the premises of the Oromia Regional State University in the east.

The invitation is extended broadly and emotionally. “Oromoon cufti, ittiin bultoonni, jaalattoonniifi leelliftoonni aadaafi duudhaa Oromoo marti koottaa waliin Jila Tajoo haa bulfannuu,” the announcement proclaims. (Oromo people, come one and all, leaders, devotees, and supporters of Oromo culture and faith, let us celebrate Jila Tajoo together at the appointed time.)

The event serves a threefold purpose deeply embedded in the Oromo worldview: to celebrate and preserve ancient traditions, to express gratitude for the past, and to invoke blessings for the future. The full call translates as: Let us celebrate Jila Tajoo together, give thanks to Waaqa Uumaa (the Creator) for what has passed, and pray for milkii (abundance) for what is to come!

The gathering is not merely a ceremony but a profound communal experience, a reaffirmation of identity. It promises a full sensory immersion in Oromo heritage, culminating in the evocative closing line: “Ijaan aaga argaa; gurraan nagaa dhagayaa!” (May our eyes see wonder; may our ears hear peace!)

This celebration stands as a powerful testament to the living, breathing nature of Oromo cultural and spiritual systems, inviting a collective experience of gratitude, hope, and enduring tradition.

Australia Mourns Bondi Victims with Light and Silence, as Communities Reaffirm Hope

January 22, 2026 | AUSTRALIA – Today, Australia stands still in a sombre moment of national unity, observing a National Day of Mourning for the 15 lives taken in the devastating terrorist attack at Bondi’s Jewish community centre last month.

The Day of Mourning has been declared as a time for collective reflection, with all Australians called upon to join together in grief and solidarity. “It is a day for all Australians to come together to grieve, remember, and stand against antisemitism and hate,” a government statement affirmed.

In a series of formal tributes, flags are being flown at half-mast across federal and Victorian government buildings. As evening falls, iconic landmarks throughout Victoria will be illuminated in white—a powerful visual symbol of resilience, peace, and the collective determination to move forward.

At exactly 7:01 PM, the time the attack unfolded on December 14, 2025, the nation is invited to pause for a minute of silence—a shared moment to remember the innocent victims whose lives and futures were violently cut short.

Personal Acts of Remembrance Echo National Resolve

The official day of mourning is mirrored in the private homes of Australians from all walks of life, where the national tragedy resonates with personal histories of loss and resilience. For some, the act of remembrance is profoundly intertwined with their own experiences.

“At 7:01 PM, my family and I lit memorial candles for a minute of silence,” shared one community member, speaking from Melbourne. Their reflection wove together the national moment with a deeply personal journey: “We found the peace and freedom in Australia that was violated in our homeland, Oromia. Therefore, we condemn any act of hatred. We reiterated our hope that any darkness will be conquered by light.”

This sentiment underscores the profound significance of safety and social cohesion for Australia’s multicultural communities. For many who have sought refuge and stability, the attack strikes at the very promise of sanctuary that Australia represents.

A Nation’s Grief, A Shared Commitment

Today’s observances are more than ritual; they are a national reaffirmation of the values that bind a diverse society together. The minute of silence, the lowered flags, and the glowing white landmarks serve as public pledges against hate, offering a collective response to tragedy through unity and remembrance.

As candles flicker in windows and cities shine with light, the message echoing across the country is clear: from the depths of shared mourning arises a strengthened commitment to ensure that light—and the hope it carries—will always prevail.

The Oromo Flag: Shining Light on a Legacy of Struggle

Feature News: The Unbroken Symbol – The Oromo Flag as a Nexus of Identity and Struggle

In the annals of liberation movements, a symbol is never just cloth and color. It is a repository of memory, a map of a desired future, and a target for those who fear the unity it inspires. A recent, poignant statement from within the Oromo struggle underscores this eternal truth: “Oromoon akka mul’atuu fi dhabama irraa hafu kan godhe faajjii qabsoo kana! Alaabaa Oromoo ibsituu dukkanaa..!!” (“What made the Oromo people visible and saved them from extinction is this struggle! The Oromo flag that shines in the darkness..!!”).

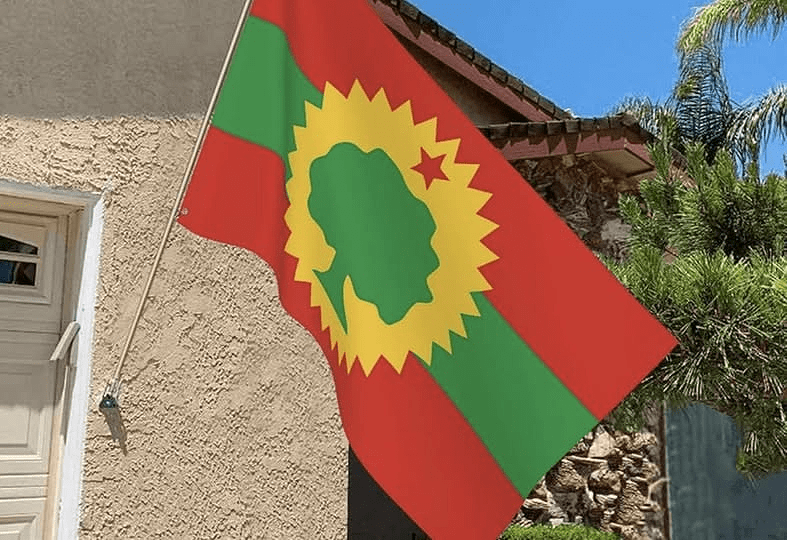

This declaration is not mere rhetoric; it is a historical verdict and a living reality. The Oromo flag—with its horizontal stripes of black, red, and white—has evolved from a clandestine emblem of resistance to a powerful, public declaration of an identity long suppressed. Its journey from the shadows into the light is the story of the Oromo people’s modern political awakening.

From Suppression to Symbol: The Flag’s Forbidden History

For decades under successive Ethiopian regimes, the display of the Oromo flag was a criminal act, punishable by imprisonment or worse. Its colors were banned, its meaning erased from official discourse in a systematic attempt to enforce cultural and political assimilation. To raise it was an act of profound bravery, a silent shout of existence against a state policy that sought to render Oromoness—Oromumma—invisible.

“The struggle gave us visibility,” the statement asserts, pointing to the decades-long political and cultural mobilization led by groups like the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF). The flag became the central emblem of this movement, its display at protests, cultural festivals, and in diasporic communities a direct repudiation of enforced silence. It transformed from a party symbol into a national one, representing not just a political program but the very sovereignty of the Oromo nation—a people with a distinct history, language, and the Gadaa system of governance.

“Shining in the Darkness”: A Beacon of Collective Memory

The phrase “shining in the darkness” is deeply evocative. The “darkness” represents eras of persecution, mass displacement, and cultural negation. The flag’s light is the enduring spirit of resistance, the scholarly work preserving Oromo history, the poets singing in Afaan Oromo, and the millions who now claim their identity publicly.

It shines on the graves of martyrs like Hundee (Ahmad Taqii), whose sacrifice was meant to sow terror but instead planted a seed of defiance. It illuminates the wisdom of oral traditions like Mirriga, which carries the constitutional memory of the people. It is the light held high by each new generation of Qeerroo and Qarree, the youth who have carried the struggle into the 21st century.

The Contemporary Crucible: Between Celebration and Conflict

Today, the flag flies openly across Oromia, a testament to a hard-won political space. It is celebrated during festivals like Irreechaa and marks public buildings. Yet, its display remains a potent and often contentious political act. To some, it is an unequivocal symbol of self-determination; to the state, its political interpretation can be seen as a challenge to national unity.

This tension ensures the flag is more than a celebratory banner; it remains a banner of contention. Each time it is raised, it reiterates the unresolved questions at the heart of the Ethiopian federation: the meaning of true multinational equality, the right to self-administration, and the legacy of a struggle that saved a people from cultural extinction.

An Amaanaa Carried Forward

The featured statement connects directly to the core Oromo concept of Amaanaa—the sacred trust of the martyrs. To bear the flag is to bear that trust. It is a vow that the sacrifice of those named in the litany of heroes—from Elemoo Qilxuu to Mecha Tullu—will not be betrayed for fleeting political gain. The flag is the physical manifestation of that covenant, a daily reminder that the visibility it represents was purchased at an incalculable price.

As one Oromo intellectual noted, the struggle is an unstoppable train; some may disembark, but the journey continues. The Oromo flag is the headlight of that train, cutting through the darkness of history, its light a constant, challenging, and unifying glow for millions. It is, as the voice from the struggle declared, the brilliant, undeniable proof that the Oromo people are here, they remember, and they endure.

A NATION IN SHADOW, A RESOLVE IN LIGHT

A National Day of Mourning: Australia Stands in Defiance and Unity After Bondi Attack

By Dabessa Gemelal

SYDNEY – Across a sun-drenched continent known for its laid-back shores, the flags are flying at half-mast today. The sea breeze at the world-famous Bondi Beach carries a new, somber weight. Australia has declared a National Day of Mourning, a unified act of collective grief and resolve following last week’s devastating terrorist attack at Bondi’s Chabad community centre, which claimed 15 innocent lives.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, in a solemn address to the nation, framed the day as a sacred covenant between the living and the lost. “Today, we honour the 15 innocent lives taken,” he stated, his words measured and heavy. “We stand with their families, their loved ones, and the entire Bondi Chabad community. We will never let hate win.”

The proclamation transforms private anguish into public ritual. Australians from all walks of life—in bustling cities, quiet suburbs, and remote outback towns—are being asked to participate in a simple, powerful ceremony of remembrance. At 7:01 PM, the exact time the attack unfolded, the nation is encouraged to pause for a minute of silence. The government has urged citizens to light a candle, a single act of defiance against the darkness of the act.

“This is a day of remembrance. And a day of unity,” Albanese emphasized, stitching together the twin threads of the national response. “Because light will always be stronger than hate.”

A Community Reeling, A Nation Responding

The attack has left the tight-knit Bondi Chabad community shattered. The centre, once a hub of prayer, learning, and fellowship, is now a site of unspeakable tragedy. Vigils of flowers, handwritten notes, and stuffed animals continue to grow at its gates, a spontaneous outcry of public sympathy.

But today, that spontaneous mourning is given a formal, national shape. The lowering of flags on government buildings, schools, and military installations is a visual echo of the nation’s lowered heart. It is a rare and significant gesture, reserved for moments of profound national loss, placing the victims in the company of fallen soldiers and revered leaders.

Sociologists Note a Shift in the National Psyche

Dr. Evelyn Shaw, a sociologist at the University of Melbourne, observes that such collective rituals serve a critical purpose. “In the face of senseless violence aimed at dividing us, the act of pausing together—whether in a city square or in our own homes at 7:01—creates a shared emotional experience. It says, ‘Your grief is our grief. Your target is our whole community.’ It actively rebuilds the social fabric terror seeks to tear.”

The call to “stand with one another” is being answered in myriad ways. Interfaith services are being held nationwide, with leaders from Christian, Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist communities expressing solidarity with their Jewish neighbours. Community centres have opened their doors for quiet reflection, and social media is flooded with images of lit candles using the hashtag #StrongerThanHate.

Light as a Weapon Against Darkness

The symbolism of light, championed by the Prime Minister, resonates deeply. It is a motif found in Judaism, the faith of the victims, where candles are lit to remember the dead and to celebrate perseverance. It is also a universal language of hope.

As dusk settles over Australia this evening, a wave of small flames will ignite in windows and on porches. That collective glow will be more than just a tribute; it will be a silent, nationwide statement. It is the light of memory, honouring 15 stolen futures. It is the light of solidarity, connecting a dispersed nation in a single, purposeful moment. And it is, as the nation’s leader has vowed, a testament to the enduring power of light over hate, of unity over division.

Today, Australia does not move on. It moves together, into the quiet of a minute’s silence, carrying the light forward.