Category Archives: Uncategorized

Dinqinesh Dheressa and Dr. Trevor Trueman: Two Pillars of the Oromo Struggle Forever Remembered with Honor

Activist and ally exemplify the international solidarity and unwavering commitment that sustain the movement for Oromo self-determination

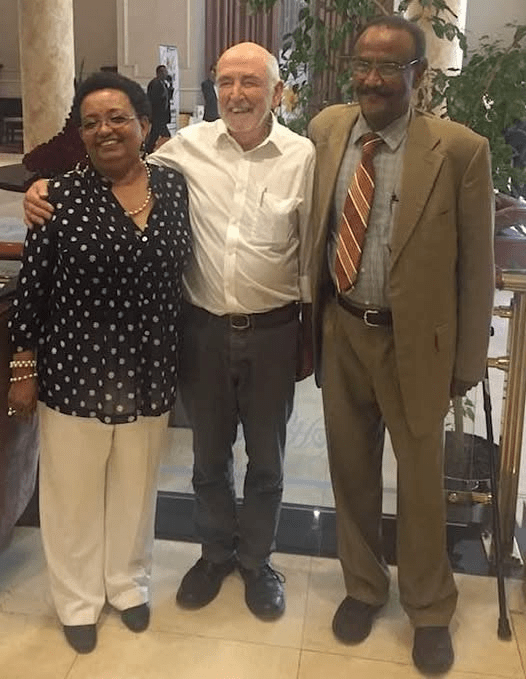

GLOBAL — Dinqinesh Dheressa and Dr. Trevor Trueman stand as figures who will forever be remembered with honor in the annals of the Oromo liberation struggle—one a devoted activist who gave voice to Oromo women’s oppression, the other a British physician who became one of the movement’s most effective international advocates.

Their contributions, though arising from vastly different backgrounds, together illustrate the multifaceted nature of the Oromo struggle: a fight carried forward not only by those who bear its identity but also by allies whose solidarity transcends ethnicity and origin. As the Oromo liberation struggle continues “as a shield of humanity strengthening humanity itself,” the legacies of Deressa and Trueman remind us that the quest for freedom draws strength from diverse sources of commitment and courage .

Dinqinesh Dheressa: A Voice for Oromo Women

Dinqinesh Dheressa Kitila is an Oromo woman whose activism emerged from personal experience of discrimination and grew into institutional leadership. As the founder of the International Oromo Women’s Organization, a non-profit registered in the United States, she has dedicated her life to standing against discrimination and bringing social change, with particular emphasis on women’s empowerment.

Born and raised in Oromia, Ethiopia, Dheressa’s commitment to justice was forged in childhood. During elementary school, when she ran for student council president, a boy was preferred over her despite her having the highest grades. This early experience of discrimination motivated her to lead a fight against discrimination against women—a fight she has continued throughout her life.

Dheressa’s analysis of Oromo women’s situation is stark and unflinching. “The state of oppression is very deep in general but Oromo women face even greater difficulty,” she has stated. “Abyssinians treat Oromo women poorly. If a woman proposes a constructive idea, it doesn’t get proper attention as women are discriminated against up to a level where they are not considered as human beings”.

For Dheressa, self-determination is not an abstract political concept but a deeply personal and practical matter. She describes it as “a process by which one can take control of her/his whole life, decide freely what is good for her/him or not, what is important to her/him.” Beyond self-determination, she sees independence as giving people “the power to act freely” .

The key to achieving self-determination, in her view, lies in empowering oppressed people and standing for their rights as human beings. She emphasizes that organization is vital—if one wants to stand for peace and especially for women and their rights, being organized is essential .

Dheressa has also consistently called upon the international community to act. “The international community and humanitarian organisations have to take appropriate action to stop the Ethiopian government’s brutality against the Oromos,” she has urged. Her work with the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) has helped bring Oromo concerns before international audiences, ensuring that the struggle receives attention beyond Ethiopia’s borders.

Dr. Trevor Trueman: The Quiet Ally

If Dheressa represents the voice of Oromo womanhood speaking on behalf of her people, Dr. Trevor Trueman represents something equally: the outsider who becomes an essential insider through decades of faithful service.

Dr. Trueman—affectionately known by the Oromo name Galatoo, meaning “Thank You”—has woven himself so deeply into the narrative of the Oromo struggle that he has become inseparable from it, transcending geography, ethnicity, and origin .

His journey with the Oromo people began not in the halls of advocacy, but in the gritty, desperate reality of survival. In the late 1980s, as a family health physician, he was in Sudan training Oromo health workers in refugee camps. When the Derg fell in 1991, he moved into Wallagga, shifting his focus to training community health workers. This foundation is crucial: his alliance was born not of abstract political theory, but of humanitarian connection—of seeing, firsthand, the people behind the cause. He didn’t arrive as an activist; he became one through service .

It was from this ground-level view that his pivotal role emerged. Starting in 1992, he began the critical, dangerous work of documenting and internationalizing the Ethiopian government’s systematic human rights violations against the Oromo people. While the OLF and others fought on the political and military fronts, Dr. Trueman opened a vital front in the global arena of information. He understood that tyranny thrives in silence and that the world’s conscience must be awakened with evidence. His reports became the credible, external voice that the diaspora and activists within could amplify, forcing the “Oromo question” onto agendas where it was being ignored .

His strategic genius is perhaps best embodied in the Oromia Support Group (OSG) , which he co-founded in 1994. The OSG was not a protest group but a clearinghouse for truth. It methodically gathered testimony, verified atrocities, and funneled this information to UN bodies, foreign governments, NGOs, and media outlets. For decades, when the Ethiopian state dismissed accusations as rebel propaganda, the OSG’s meticulously documented reports stood as unassailable counter-evidence. Dr. Trueman became a bridge of credibility, translating the suffering of a distant people into a language the international system was compelled, at least, to acknowledge .

A recent tribute to Dr. Trueman highlights several profound truths about his work:

- The Outsider as Essential Insider: Dr. Trueman’s identity as a “foreign national” was not a barrier but a unique asset. It lent his documentation a perceived objectivity that was desperately needed to break through global apathy. He wielded his privilege as a tool for the voiceless .

- Advocacy as a Marathon, Not a Sprint: His commitment, spanning from 1988 to the present day, defines “umurii dheeradhaa” —a long life of dedication. While political fortunes and rebel movements evolved, his channel of advocacy remained constant, providing a thread of continuity through decades of struggle .

- The Strategic “Taphat” (Preparation) : The tribute notes he will be remembered for his “shoora taphataniif” —his strategic preparations. His work was the essential groundwork. By ensuring the world could not plead ignorance, he created the political space and pressure that empowered all other facets of the Oromo struggle .

Dr. Trevor Trueman’s legacy is a masterclass in effective international solidarity. He did not seek to lead the Oromo struggle; he sought to amplify it. He did not fight with weapons, but with words, facts, and an unwavering moral compass. In the grand symphony of the Oromo quest for freedom, if some voices are the roaring melodies and others the steady rhythm, Dr. Trueman’s has been the crucial, clear note of the witness—persistent, truthful, and cutting through the noise to make the world listen .

For this, the name Galatoo is not merely a token of thanks, but a title of honor, earned over a lifetime. His work ensures that the crimes committed in darkness are recorded in light, and that the struggle of the Oromo people has, indeed, been given an echo the world cannot un-hear .

The Struggle Continues

The Oromo liberation struggle, which both Dheressa and Trueman have served so faithfully, continues today against a backdrop of ongoing conflict and human rights concerns. Recent reports from Oromia describe a region marked by insecurity, with civilians caught between government forces and insurgent groups.

The Associated Press reported in February 2026 that Oromia remains “very insecure,” with armed banditry, kidnapping, and extortion affecting daily life. Humanitarian access is restricted, and the conflict remains largely underreported due to government restrictions on journalists and rights groups .

It is precisely in such circumstances that the work of advocates like Dheressa and Trueman proves most vital. Their documentation, their amplification of Oromo voices, and their insistence that the world pay attention create the conditions under which accountability becomes possible.

As one tribute to Trueman noted, “His work ensures that the crimes committed in darkness are recorded in light” . Dheressa, through her women’s organization and international advocacy, ensures that the particular suffering of Oromo women—too often ignored in broader narratives—receives the attention it demands.

A Shared Legacy

Dinqinesh Dheressa and Dr. Trevor Trueman represent different faces of the same commitment: Dheressa, the Oromo woman who transformed personal experience of discrimination into lifelong activism for her people; Trueman, the British physician who arrived as a humanitarian worker and became one of the movement’s most effective international advocates.

Both have demonstrated that the struggle for Oromo self-determination is not confined to Oromia’s borders, nor limited to those who share Oromo identity. It is a human rights struggle that calls upon all people of conscience to bear witness and to act.

As the Oromo liberation continues as “a shield of humanity strengthening humanity itself,” the contributions of these two figures will forever be remembered with honor. Their lives demonstrate that the fight for freedom draws strength from many sources—from the mother who organizes women in her community to the physician who documents atrocities for the United Nations. Each, in their own way, has helped ensure that the Oromo struggle for truth, justice, and self-determination continues to resonate across generations and around the world.

Exploring Indigenous Peacemaking at the 2026 Oromo Conference

Oromo Studies Association Honors Legacy of Prof. Hamdessa Tuso with Mid-Year Conference on Conflict Resolution and Peace-Building

Scholars and researchers invited to explore indigenous peacemaking traditions at University of Minnesota gathering

MINNEAPOLIS — The Oromo Studies Association (OSA) has issued a call for papers and panels for its 2026 Mid-Year Conference, scheduled for April 11-12 at the University of Minnesota Medical Center’s West Bank campus. This year’s gathering carries special significance as it will honor the life and legacy of Professor Hamdessa Tuso, a founding member of OSA and a towering figure in the study of indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms .

Under the theme “Conflict Resolution & Peace-Building: Honoring the Life and Legacy of Prof. Hamdessa Tuso,” the conference invites scholars, researchers, and community leaders to submit abstracts exploring the rich traditions of peacemaking that have sustained Oromo society for generations. The event will take place at 2450 Riverside Ave, Minneapolis, MN 55454.

A Life Devoted to Indigenous Peacemaking

Professor Hamdessa Tuso, who passed away on November 22, 2025, in Winnipeg, Manitoba, dedicated his life to studying and teaching about African indigenous conflict resolution processes . His scholarly work emphasized that indigenous forms of peacemaking—long dismissed by Western academics as “irrelevant and backward tribal rituals”—contain sophisticated mechanisms for building lasting peace .

Dr. Tuso earned his Ph.D. in Conflict Resolution and Peacebuilding from Michigan State University in 1981 and served in distinguished academic roles across North America, including as Professor of Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Manitoba and as a faculty member at Nova Southeastern University . His landmark work, “Creating the Third Force: Indigenous Processes of Peacemaking,” which he co-edited with Maureen P. Flaherty, presented the Oromo Gadaa system as a global model for conflict resolution .

In that seminal volume, Tuso contributed chapters including “Indigenous processes of conflict resolution: neglected methods of peacemaking by the new field of conflict resolution” and “Ararra: Oromo indigenous processes of peacemaking,” establishing a scholarly foundation for understanding how Oromo traditional institutions can address contemporary conflicts .

Conference Theme and Significance

The conference announcement highlights the Oromo people’s historical role as “the anchoring population that cemented the coexistence of peoples of various creeds” and “guarantors of peace, stability and justice everywhere its rule prevailed.” According to the call for papers, historical accounts indicate that before the precolonial era, the Oromo managed to create alliances with neighboring tribes, transforming former rivals into partners.

The announcement also addresses historical challenges to Oromo recognition: “Since the formation of Ethiopia as an empire State, the Oromo people were brutally oppressed, marginalized, dehumanized and the contributions of the Oromo to maintaining peace and stability in the horn of Africa were denied the due recognition they deserved in history.”

It was not until the early 1970s that organized scholarly attention began to reveal “the hidden truth that the Oromo in fact are custodians of indigenous institutions of governance that guarantees equality of all its citizens, rule of law, justice and fairness for all living things and the environment.”

The conference draws on core Oromo values of Nagaa (peace) and Araara (reconciliation)—traditional principles that guide conflict resolution when disputes arise between groups and individuals. As the call for papers notes, “The Oromo Land is therefore rightly described as the sea of blessings, where elders call for peace to prevail over everything living and the environment.”

Call for Submissions

OSA invites abstracts for individual paper presentations, posters, panels, and roundtables addressing the conference theme and the following sub-themes:

- Indigenous Oromo institutions: exploring the mechanisms of peacebuilding and conflict resolution

- Mitigating intra-ethnic conflicts in Ethiopia, the Horn of Africa and elsewhere globally: lessons learned from other settings

- Building peace and resolving conflicts among the Oromo and neighboring nations and nationalities (such as Somali, Afar, Sidama) past, present, and future

- Federalization and exclusion of Oromo cities Harar, Dire Dawa, Jigjiga: case studies of the impact of forced division on Oromo approaches to peacebuilding and stability

- Dedicated Panel: Remembering the Life and Legacy of Prof. Hamdesa Tuso — welcoming reflections on how he approached the study of conflict resolution

- Examining women’s leadership in traditional Oromo peacebuilding and conflict resolution

- Transmitting the wisdom of peacebuilding to the younger generation in a time of intense war, violence and undermining of culture

Other topics will be considered, but priority will be given to abstracts relevant to the theme and sub-themes.

Submission Guidelines

Individual Papers or Posters: Submissions should include a 200-300 word abstract providing 1) title, 2) specific contribution to the theme, 3) evidence on which the presentation is based, and 4) brief findings or conclusions. Authors must include names, country of residence, affiliation, field of specialization, and contact information (email and WhatsApp).

Panels: Panels consist of four members of a pre-assembled group. Proposals should include the panel title and brief biographies of each panel member with academic credentials or community roles.

Roundtables: Roundtables bring together qualified scholars and prominent personalities moderated to discuss a specific topic, book, or research finding. Submissions should include the roundtable title, relevance to the conference theme, moderator information, and speakers’ names with contact details.

The deadline for submission is March 10, 2026, at midnight. Acceptances will be notified on a rolling basis, with final notices made by March 21. All submissions should be sent to: oromostudiesassociation@gmail.com

A Legacy of Scholarship and Advocacy

Professor Tuso’s contributions extended far beyond academia. He was among the earliest pioneers of the Arsi Basic School movement, helping ignite a culture of learning across Arsi in Oromia at a time when education itself was considered a revolutionary act . He championed Tokkumaa Oromoo (Oromo unity) and stood firmly against what he termed “the colonization of the Oromo mind.”

His service included organizing the Oromo Committee for Immigration and Refugees (OCIR) in the 1980s, helping secure asylum for thousands of Oromos in the United States at a time when the U.S. government had restricted asylum for Ethiopians . He also participated in the 1991 London Peace Conference, advocating for a just political reordering of Ethiopia .

As a founding force behind the Oromo Studies Association and its first president, Tuso nurtured generations of scholars committed to researching and preserving Oromo history and culture . The upcoming conference represents a continuation of that mission, bringing together researchers to explore how indigenous wisdom can address contemporary challenges.

For scholars of peace and conflict studies, African studies, and indigenous governance systems, the April conference offers a unique opportunity to engage with Oromo intellectual traditions at a moment of both remembrance and renewal.

Ethiopia Marks 14th World Radio Day with a Focus on Diversity and Community Service

ADDIS ABABA — Ethiopia joined the global community today in celebrating the 14th World Radio Day under the theme “Radio and Artificial Intelligence.” In a message marking the occasion, the Ethiopian Media Authority (EMA) highlighted the medium’s indispensable role in serving the nation’s diverse population and reaffirmed its commitment to supporting the sector’s growth.

“Happy World Radio Day to all radio journalists, editors, leaders, and listeners across our nation!” declared Haimanot Zelake, Director General of the Ethiopian Media Authority, in a statement released to the press .

The global observance, celebrated annually on February 13, has a rich history. The concept was initiated by the Spanish Radio Academy, and the formal proposal was presented to UNESCO in 2010. It was proclaimed by UNESCO in 2011 and subsequently adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 2012, with February 13 chosen to commemorate the establishment of United Nations Radio in 1946 . This year marks the 14th time the day has been celebrated worldwide .

The Enduring Power of Radio in Ethiopia

In her message, Director General Zelake underscored the unique and vital role radio plays in Ethiopia’s specific context. As a low-cost and accessible medium, radio remains the primary source of information, education, and entertainment for communities across the country, effectively serving as a cornerstone for public discourse and democratic engagement .

“Radio plays a unique role in informing, educating, and entertaining the public,” Zelake stated. “Given our national context, its importance is extremely high, serving as a key source of information in almost all areas.”

The Ethiopian Media Authority, empowered by its founding legislation, views radio as essential for guaranteeing the public’s right to information and ensuring media accessibility . The Authority’s mandate includes licensing, monitoring, and supporting media outlets to create an enabling environment for them to flourish.

A Growing and Diverse Radio Landscape

The Director General provided an encouraging update on the state of the industry, highlighting a significant expansion in the number of radio stations operating under the Authority’s license. Currently, Ethiopia is home to a vibrant mix of 57 radio stations, comprising:

- 31 Public radio stations

- 10 Community radio stations

- 11 Commercial radio stations

- 5 Educational radio stations

This diverse media landscape ensures that a multitude of voices and perspectives are represented, catering to the varied interests of the Ethiopian populace. “Radio stations operate by taking into account the diverse thoughts and interests of society,” Zelake emphasized.

Amplifying Community Voices

A key focus of the Authority’s work, as outlined in the message, is the expansion and strengthening of community radio. These stations are vital for reaching remote and vulnerable groups, giving a platform to the illiterate, women, youth, and marginalized communities to participate in public debate .

Haimanot Zelake stressed that beyond issuing licenses, the Authority is actively creating support frameworks to help community stations thrive. This support is crucial for ensuring that Ethiopia’s nations, nationalities, and peoples can use their languages and promote their cultures and values. The Director General reiterated that the Authority’s commitment to this cause will continue to be strengthened.

“As we celebrate this day, I want to reaffirm that the Authority’s support in this regard will continue to be strengthened,” she said. “The role of radio in enabling nations, nationalities, and peoples to use their own languages and promote their culture and values is immense.” .

As Ethiopia celebrates this World Radio Day, the message from the EMA is clear: radio is not a dying medium but a resilient and evolving force for unity, information, and community empowerment, and its growth will continue to be a national priority.

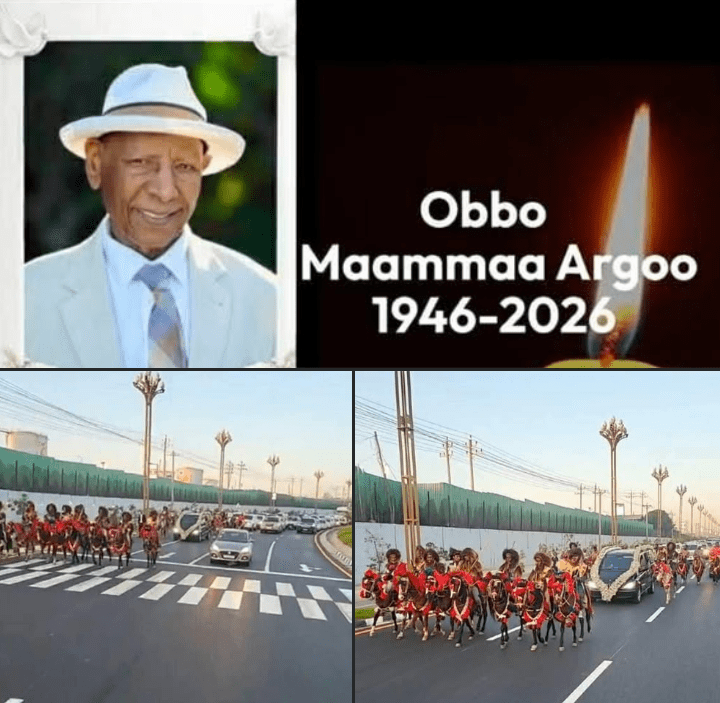

A Titan’s Farewell: Seattle Bids Final Goodbye to Obbo Maammaa Argoo, Pillar of the Oromo Struggle

Subtitle: A Hero’s Funeral at Bole International Airport Honors a Life of Service, From Shashamanne to Seattle.

SEATTLE, USA – Under solemn skies, the global Oromo community gathered at Bole International Airport to perform the final rites of honor (Sirna Simannaa) for a true giant of the Oromo struggle and a foundational pillar of the diaspora: Obbo Maammaa Argoo.

His passing marks not just a personal loss, but the closing of a chapter in modern Oromo history. Obbo Maammaa Argoo was a man who never left the side of his people, fighting for Oromumma until his final breath, as his life story powerfully attests.

The dignified funeral service was attended by elders, prominent figures, political leaders, and countless community members, a testament to the vast and profound impact of his decades of unwavering service.

A Life of Action, From the Heart of Oromia to the Heart of the Diaspora:

Born in 1946 in Shashamanne, West Arsi, Obbo Maammaa Argoo’s commitment to his people ignited early. In the 1960s, he and his peers launched literacy campaigns in their local area, establishing schools and teaching in remote villages—a foundational act of empowerment.

After immigrating to the United States in 1989, settling first in Washington D.C. and then moving to Seattle in 1992, he immediately began serving the Oromo community with visionary leadership. He helped build the Seattle Oromo community from the ground up, serving in various leadership capacities.

His legacy is etched in the preservation of identity. For over 27 years, he tirelessly organized weekly programs to teach Oromo children their language, culture, history, and sense of self—ensuring the flame of Oromumma burned bright in a new land.

He was also a key architect of unity and institution-building. His instrumental role in founding the Oromo Soccer Federation and Sports Association in North America (OSFNA) stands as a monumental achievement, creating a lasting platform for community cohesion, pride, and networking across the continent.

A Man of Family and Principle:

Beyond his public life, Obbo Maammaa Argoo was a devoted family man, a loving husband, and a father to five children. He was widely known as a steadfast advocate for human rights and actively participated in numerous charitable and social service initiatives in Seattle.

Today, as we lay him to rest at Bole International Airport, we do not say goodbye to his spirit. We commit to carrying forward the institutions he built, the language he taught, and the unwavering love for Oromia he embodied. His name will forever be synonymous with dedication, resilience, and the boundless potential of community service.

Rest in perfect peace, Obbo Maammaa Argoo. Your work is done, but your light will forever guide our path.

#MaammaaArgoo #OromoHero #SeattleOromo #OSFNA #OromoDiaspora #RestInPower #Simannaa

The Power of the Table: Why Choosing to Sit Down is Africa’s Greatest Political Strength

A Look at the Psychological, Democratic, and Social Benefits of Dialogue

Across our world, diverse societies are navigating complex conflicts and seeking their own solutions, evolving with the times. While African communities have long-held methods for resolving disputes, there is one universal, key action that binds them all: choosing to sit down and talk.

The act of sitting down to negotiate is a cornerstone of national dialogue, conflict resolution, and peacebuilding processes. What positive contributions does it make? The following points explain:

👉 Psychological Benefits:

Studies in this field show that when conflicting parties willingly sit down to talk, numerous psychological advantages emerge. When people sit down to dialogue, they enter a state of mental calm. By exercising self-control and utilizing their capacity for reason, their stable personality is actualized. This creates a favorable condition for discussion and debate, moving away from raw emotion and toward reasoned exchange.

👉 Democratic Benefits:

The act of sitting down to negotiate is, in itself, a demonstration of achieved equality. When all parties sit for discussion, it is a visible sign that none are inherently superior to the others. Furthermore, in forums like national dialogues, people gathering in a circular formation helps balance power dynamics, symbolizing that all voices hold space and that no single position dominates.

👉 Benefits Based on Social Trust:

In a national dialogue process, the preparation and willingness of all stakeholder groups to sit together and talk in unity builds mutual trust. It moves parties away from thinking, “The other side wants to destroy us,” and instead permits them to express their opposition, concerns, and desires, and to listen to the other’s. This fosters and deepens trust, which is the essential foundation for any lasting agreement.

The Ethiopian National Dialogue Commission embodies this critical philosophy. By creating the literal and figurative table around which Ethiopians can sit, it seeks to harness these very benefits—psychological calm, democratic equality, and social trust—to navigate the nation’s complex challenges. The simple, profound act of taking a seat is the first step in moving from confrontation to conversation, and from conflict to shared understanding.

#Dialogue #Peacebuilding #NationalDialogue #ConflictResolution #Africa #Ethiopia #SocialCohesion

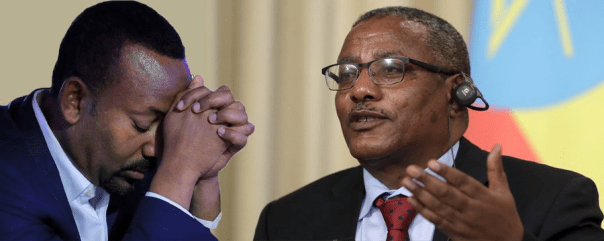

Ethiopian Ex-Foreign Minister’s Open Letter Challenges PM Abiy’s War Accounts

Former Ethiopian Foreign Minister Challenges PM Abiy’s War Narrative in Explosive Open Letter

ADDIS ABABA – 5 FEBRUARY 2026 – In a remarkable and unprecedented public rebuke, Gedu Andargachew, a former high-ranking Ethiopian official, has published a detailed open letter directly contradicting Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s account of Eritrea’s role in the Tigray war and alleging the PM displayed open contempt for the Tigrayan people.

The letter, addressed to “His Excellency Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed,” is a point-by-point rebuttal of statements Abiy made in Parliament on February 3, 2026, where the Prime Minister cited Gedu as a witness regarding Ethiopia-Eritrea relations.

Direct Challenge on Eritrea’s Role

Gedu’s most significant claim fundamentally alters the official narrative of the 2020-2022 war. He asserts that the Eritrean army was a consistent, integrated ally of the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) from the very beginning.

“From the outset of the war in Tigray until it was halted by the Pretoria Agreement, there was hardly a moment when the Eritrean army was not fighting alongside the Ethiopian National Defense Forces,” Gedu writes. He provides a specific military detail, alleging that when Tigrayan forces advanced into the Amhara region in mid-2021, “the Eritrean army operated as far as the vicinity of Debre Tabor.”

He states the two armies functioned as “a single force” and only ceased joint operations after the Pretoria ceasefire was announced, directly challenging narratives that sought to minimize or obscure the extent of Eritrean involvement.

Allegations of Moral Failure and Deflection

The letter accuses PM Abiy of avoiding responsibility for the war’s catastrophic human toll. “After such widespread destruction, I expected that you would seek forgiveness from both the people of Tigray and the people of Ethiopia,” Gedu states. Instead, he claims the Prime Minister engages in “distorted” storytelling to “deflect responsibility.”

Gedu links the Tigray conflict to ongoing crises in Amhara, Oromia, Benishangul, and Gambella, arguing they are “primarily the result of your weak governance and the mistaken belief that political survival requires perpetual conflict.”

Explosive Claim of Abiy’s Contempt for Tigrayans

The letter’s most incendiary passage recounts a private meeting Gedu says occurred after the capture of Mekelle in late 2020. After Gedu advised establishing civilian rule to avoid fueling resentment, he claims Abiy summoned him and expressed a radically different view.

Gedu quotes the Prime Minister as allegedly saying:

“Gedu, do not think the Tigrayans can recover from this defeat and rise again. We have crushed them so they will not rise… Who are the people of Tigray above? We have broken them so they will not rise again. We will break them even further. The Tigray we once knew will never return.”

Gedu presents this as evidence of Abiy’s “true attitude toward the people of Tigray.”

Denying a Secret Humanitarian Mission

Gedu forcefully denies Abiy’s parliamentary claim that he was sent to Eritrea as a special envoy concerning atrocities in Tigray. He clarifies he resigned as Foreign Minister “within days of the outbreak of the war.”

He confirms a single trip to Asmara in early January 2021 but describes a mission with three military-focused objectives: congratulating President Isaias Afwerki on joint operations, thanking Eritrea for hosting the shattered Northern Command, and coordinating a response to mounting international “human rights violations” allegations.

Critically, Gedu claims that when he suggested asking Eritrea to withdraw its forces—as the international community demanded—Abiy explicitly forbade it. “You explicitly instructed me not to raise this issue under any circumstances,” he writes. He states unequivocally that “no message whatsoever concerning the suffering of the people of Tigray was conveyed.”

A Call for Historical Truth

Presented as a necessary act of conscience, Gedu’s letter concludes, “This is the truth as I know it.” It stands as a direct challenge from within the former political establishment to the Prime Minister’s version of history, demanding a reckoning with the war’s conduct and moral consequences that, the author implies, has yet to occur.

The Prime Minister’s office has not issued an immediate public response to the allegations.

For more detail see the official Amharic letter of Gedu Andargachew

For more information see the English copy of the letter of Gedu Andargachew

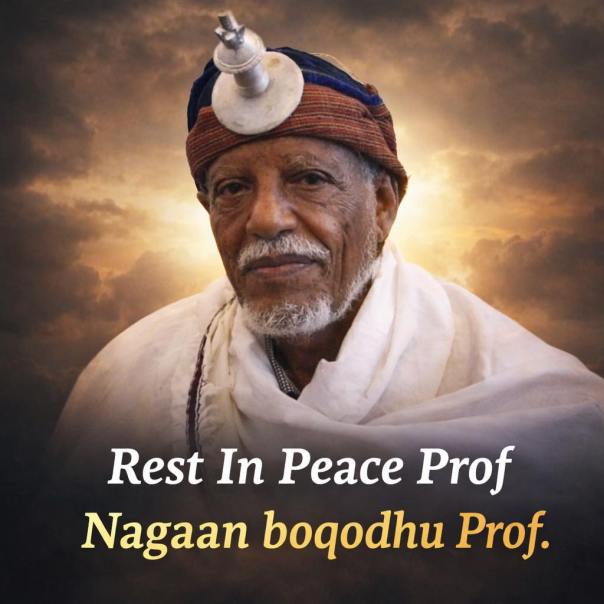

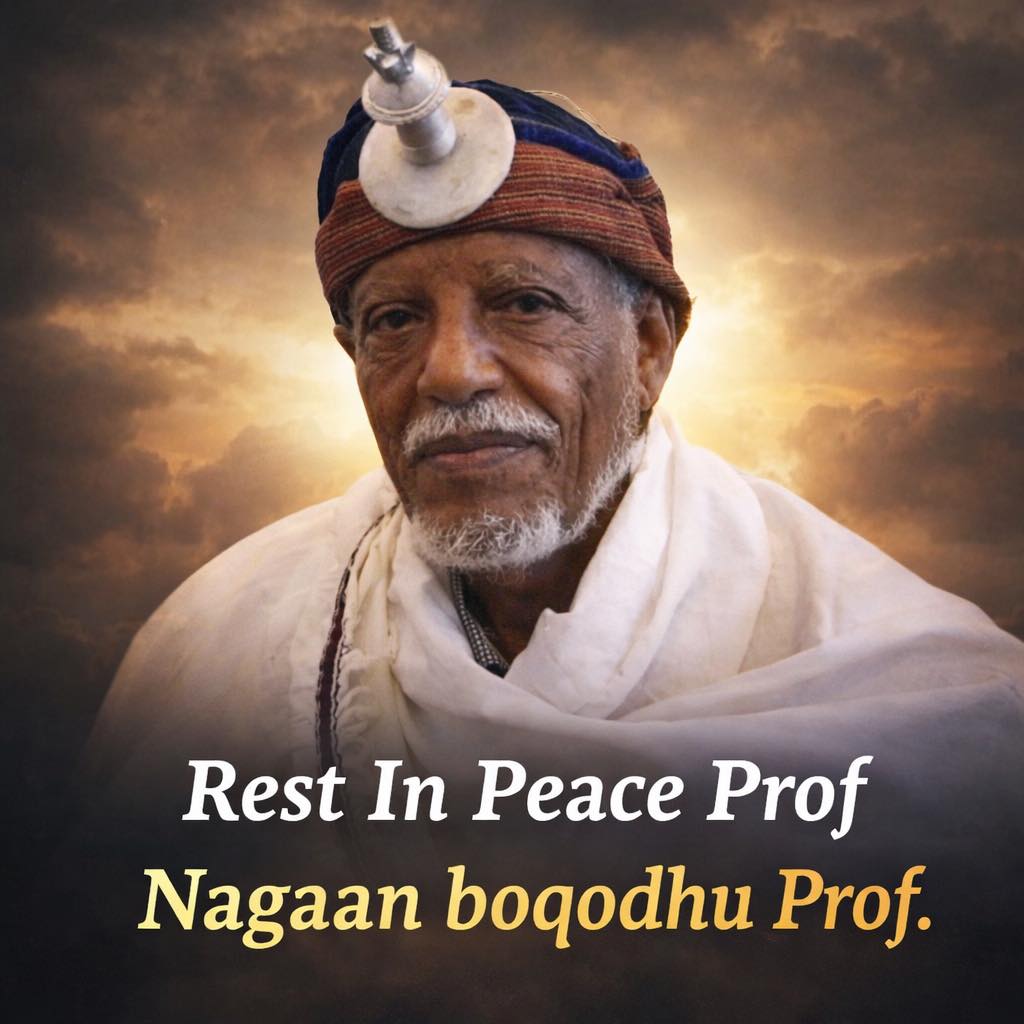

Borana University Remembers Professor Legesse: Indigenous Knowledge Advocate

Borana University Mourns a Beacon of Indigenous Knowledge: Professor Asmarom Legesse

(Yabelo, Oromia – February 5, 2026) Borana University, an institution deeply embedded in the cultural landscape it studies, today announced its profound sorrow at the passing of Professor Asmarom Legesse, the preeminent anthropologist whose lifelong scholarship fundamentally defined and defended the indigenous democratic traditions of the Oromo people. The University’s tribute honors the scholar not only as an academic giant but as a “goota” (hero) for the Oromo people and for Africa.

In an official statement, the University highlighted Professor Legesse’s “lifelong dedication to understanding the complexities of Ethiopian society—especially the Gadaa system,” crediting him with leaving “an indelible mark on both the academic and cultural landscapes.” This acknowledgment carries special weight from an institution situated in the heart of the Borana community, whose traditions formed the bedrock of the professor’s most celebrated work.

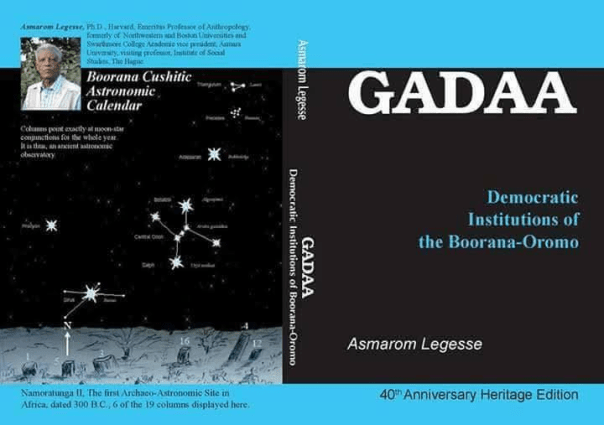

The tribute detailed the pillars of his academic journey: a Harvard education, esteemed faculty positions at Boston University, Northwestern University, and Swarthmore College, and the groundbreaking field research that led to his seminal texts. His 1973 work, “Gada: Three Approaches to the Study of African Society,” was cited as revolutionary for revealing “the innovative solutions indigenous societies developed to tackle the challenges of governance.”

It was his 2000 magnum opus, however, that solidified his legacy as the definitive voice on the subject. In “Oromo Democracy: An Indigenous African Political System,” Professor Legesse meticulously documented a system characterized by eight-year term limits for all leaders, a sophisticated separation of powers, and the Gumi assembly for public review—a structure that presented a centuries-old model of participatory democracy. “His insights challenged prevalent misconceptions about African governance,” the University noted, “showcasing the rich traditions and political innovations of the Oromo community.”

For his unparalleled contributions, he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Letters from Addis Ababa University in 2018.

Perhaps the most powerful element of the University’s statement was its framing of his legacy beyond academia. By “intertwining the mechanics of the Gadaa system with the broader narrative of Oromo history and cosmology,” Professor Legesse was credited with fostering “a profound understanding of Oromo cultural identity.” It is for this work of preservation, interpretation, and transmission that he is declared “a hero—a goota—to the Oromo people and to Africa as a whole.”

Looking forward, Borana University management has called upon its students and faculty to honor his memory through “ongoing research and discourse on indigenous governance systems,” ensuring his foundational work continues to inspire new generations of scholars.

The entire university community extended its deepest condolences to Professor Legesse’s family, friends, and loved ones, mourning the loss of a true champion of Oromo culture and a guiding light in the study of African democracy.

About Borana University:

Located in Yabelo, Borana Zone, Oromia, Borana University is a public university committed to academic excellence, research, and community service, with a focus on promoting and preserving the rich cultural and environmental heritage of the region and beyond.

Remembering Professor Asmerom Legesse: A Legacy of Oromo Democracy

A World Mourns an Intellectual Giant: Tributes Pour In for Professor Asmerom Legesse, Scholar of Oromo Democracy

[Global] – February 2026 – The passing of Professor Asmerom Legesse has triggered a profound wave of mourning across academic, cultural, and political spheres, uniting voices from the Oromo diaspora to global institutions in tribute to the man who single-handedly brought the sophisticated Oromo Gadaa system to the world’s attention. Recognized as the preeminent global authority on the subject, his death at the age of 89 is being hailed as an irreplaceable loss to indigenous knowledge and the study of African democracy.

Condolence statements from major Oromo organizations, scholars, and advocates paint a consistent portrait of Professor Legesse: not merely an academic, but a bridge-builder, a truth-teller, and a steadfast guardian of a cultural heritage long marginalized. His life’s work is credited with fundamentally reshaping global understanding of the Oromo people and providing the intellectual foundation for their cultural and political identity.

Scholars and Intellectuals Honor a Pioneer

Prominent Oromo scholar Prof. Asfaw Beyene remembered him as a “sincere friend of the Oromo people,” whose life was “defined by wisdom, integrity, and an unwavering commitment to revealing truths long ignored by entrenched systems.” This sentiment was echoed by commentator Habtamu Tesfaye Gemechu, who stated Legesse was the scholar who “shattered the conspiracy” of Ethiopian rulers and intellectuals to obscure Oromo history, “revealing the naked truth of the Oromo to the world.”

Jawar Mohammed emphasized the practical depth of Legesse’s scholarship, noting his “decades of dedicated field research” and “deep engagement with Borana-Oromo communities” which helped “bridge the transmission of Gadaa knowledge from our ancestors to the present generation.”

Institutional Tributes Highlight Global Impact

Major Oromo institutions have issued formal statements underscoring the monumental scale of his contribution. The Oromo Studies Association (OSA), which honored him with a Lifetime Achievement Award, stated his “groundbreaking work fundamentally reshaped the global understanding of African democracy,” providing the academic backbone for UNESCO’s 2016 recognition of Gadaa as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Advocacy for Oromia hailed him as a “preeminent global ambassador” for Gadaa, whose work performed a “vital act of cultural reclamation and global education.” Similarly, The Oromia Culture and Tourism Bureau praised his “indispensable role in safeguarding the philosophical foundations and moral values that define Oromo identity.”

A Legacy of Pride and Empowerment

For the broader Oromo community, his passing is deeply personal. Activist Bilisummaa A. Qubee captured this sentiment, stating, “Prof. Asmarom Legesse has a great legacy of making Oromo identity known at a global level for us! His history lives with the Oromo!” This reflects the prevailing view that his rigorous scholarship—epitomized by definitive texts like Gada: Three Approaches to the Study of African Society and Oromo Democracy: An Indigenous African Political System—did more than analyze; it restored dignity and provided a source of immense pride.

As tributes continue to pour in, the consensus is clear: while Professor Asmerom Legesse’s voice is silent, his foundational work ensures that the Gadaa system—a complex indigenous framework of democracy, justice, and social order—will remain a lasting part of humanity’s intellectual heritage, inspiring generations to come.

Advocacy for Oromia Condemns Bondi Violence

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Advocacy for Oromia Condemns Bondi Attack, Stands with Jewish Community

MELBOURNE, VIC – 15 December 2025 – Advocacy for Oromia has issued a strong statement condemning yesterday’s horrific attack at Bondi Beach and expressing unwavering solidarity with the Australian Jewish community. The organisation denounced the violence as an attack on shared Australian values and a profound violation of human dignity.

In the statement, Advocacy for Oromia expressed “profound sorrow” for the victims, their families, and all those affected, calling the act an “affront to our common humanity” that inflicts “unimaginable trauma and grief.” The group highlighted the particular cruelty of the timing, noting the attack occurred on the first day of Hanukkah—a celebration of “light, faith, and joy”—thereby framing it as “an especially disturbing act of hatred, antisemitism, and terrorism.”

“Such violence strikes not only at one community, but at the very heart of Australia’s shared values: compassion, respect, and peaceful coexistence,” the statement read.

The advocacy group emphasised that terrorism and hate have no place in Australia, warning of the deep and lasting scars such events leave on the entire national fabric, creating fear and heartbreak far beyond the immediate victims.

A Call for National Unity and Compassion

In response to the tragedy, Advocacy for Oromia issued a call for unity, urging Australians to draw strength from the nation’s diversity. “Our strength has always resided in our diversity—in people of all faiths and cultures, from over 236 backgrounds, standing side by side in empathy and mutual respect,” the statement affirmed.

The organisation declared its firm solidarity with Jewish Australians, reaffirming a “shared commitment to peace, dignity, and our common humanity.” It advocated for a collective response rooted in compassion and unity rather than fear and division.

“Let us respond not with fear, but with compassion; not with division, but with unity,” the statement concluded. “May we support one another, honour those who have been impacted, and continue building an Australia where every person feels safe, valued, and supported—in both body and mind.”

About Advocacy for Oromia: Advocacy for Oromia is an organisation dedicated to promoting human rights, justice, and the welfare of the Oromo people, while engaging in broader humanitarian and solidarity efforts within the Australian and global community.

The full statement from Advocacy for Oromia is available for review.

Honoring Elder Oromo Community Leader Hayile Qeerransoo

On Friday, December 12, 2025, members of the Oromo community gathered at the home of Mr. Hayile Qeerransoo to honor him and offer their companionship.

Mr. Hayile, an elder who has withdrawn from public life in recent years and whose wife passed away few years ago, was visited by community members who expressed their affection and gratitude.

Mr. Hayile, in turn, thanked those who organized and attended the gathering.

Such visits reflect the Oromo cultural tradition of honoring and supporting elders who have dedicated their lives to the community.

Honoring Oromo community leaders is a deep-rooted cultural tradition, exemplified by specific ceremonies that recognize the vital role of elders and pioneers in preserving culture, providing guidance, and advocating for justice