From Shared Purpose to Genuine Solidarity: Moving Beyond Empty Unity

In Loving Memory of Kumsa Burayu, Devoted Advocate for Oromo Unity

Worku Burayu (Ph.D.)

Introduction

The passing of my younger brother, Kumsa Burayu, who gave his life to the cause of Oromo unity, has compelled me to write this article—both as a tribute to his memory and as a call to move beyond empty declarations of unity toward true solidarity. His lifelong devotion to the Oromo struggle was not grounded in slogans or fleeting alliances, but in an unshakable belief that our people can only be free through trust, sacrifice, and principled action.

Unity has long been invoked in the Oromo struggle for justice and self-determination. Yet too often, it has been reduced to rhetoric, fragile declarations that collapse under pressure, leaving our people vulnerable to division and betrayal. My baby brother, Kumsa Burayu, who recently passed away in his mid-fifties, saw this danger clearly. Throughout his life, he fought not for the shallow comfort of empty unity, but for the deeper, more demanding work of genuine solidarity. His commitment was not abstract. He lived it. Kumsa gave his time, his energy, and ultimately his life’s strength to ensure that Oromo unity was not a slogan but a living principle. He believed that real solidarity requires honesty, trust, and sacrifice—that it is built not on convenience or temporary alliances, but on an unshakable commitment to the collective good.

Superficial unity may rally a crowd, but it cannot sustain a movement. Only solidarity—rooted in truth and accountability—can carry us forward. Kumsa’s journey reminds us that the struggle for Oromo freedom and dignity cannot rest on half-hearted promises. It demands integrity, courage, and the willingness to put principle above personal gain.

This dedication is both personal and public. It honors the memory of Kumsa Burayu, whose heart never wavered, and it carries his message forward: that we must rise beyond empty unity and embrace genuine solidarity. Only then can we fulfill the vision of justice and self-determination for which he and countless others, gave everything.

Unity in Ethiopian Political History

The idea of unity has often been used and abused in Ethiopian political history. Regimes from Menelik to Haile Selassie, and later the Derg, weaponized unity to dominate, silence, and homogenize. Under slogans like “Ethiopia First,” the Derg vilified groups like the OLF and TPLF as threats to national unity. Even after the fall of the military regime, unity remained an ideological tool, sometimes used to marginalize dissent in the name of national cohesion. Ethnic federalism under the EPRDF shifted the conversation but did not resolve the underlying tensions.

Today, unity still risks becoming a hollow word, uttered in songs, rallies, and political speeches, but empty of shared meaning. The only way to move beyond that is to redefine unity as solidarity with justice. We must stop romanticizing unity as a fixed ideal and start building it as living practice.

The Use and Abuse of the Word Unity in Oromo Politics

The concept of unity has long served as a unifying call for the Oromo liberation movement. Freedom fighters, activists, politicians, civil society organizations, artists and religious leaders have consistently invoked it. For decades, appeals for unity have been a central theme in Oromo public life. They have been articulated at conferences devoted to liberty, equality, and democracy; voiced through speeches at political and cultural gatherings; expressed in the lyrics of Oromo musicians during festivals; and reiterated by keynote speakers across a wide range of forums. From the seminal addresses of the Mecha Tulama Association to the slogans advanced by Qeerroo and Qaarree youth movements, unity has consistently been framed as a sacred and non-negotiable principle. Indeed, it constituted a decisive force in the eventual dislodging of the TPLF-led EPRDF regime.

Yet in Oromo politics, the word “unity” has become both overused and misused. We have accepted unity as a panacea for all ills—political repression, social injustice, internal division—without interrogating what it truly means. Often, unity’s absence is blamed for failed movements, and we mistakenly equate unity with uniformity. But true unity does not demand ideological uniformity. It is the ability to come together with our differences intact, guided by a shared vision and purpose.

What Unity Really Means

In my views, unity means coming together around shared goals such as freedom, justice, and the protection of Oromo identity—despite differences in region, religion, or political affiliation. It reflects a commitment to the collective good over personal or group interests. True unity is rooted in the values of the Gadaa system, where dialogue, consensus, and mutual respect guide decision-making. It demands tolerance and a willingness to cooperate even when perspectives diverge. It embraces our differences as strengths while working together toward common goals. True unity is grounded in a clear sense of purpose and a collective commitment to that purpose. It is not measured by the absence of conflict but by the strength of collaboration in the face of complexity. In its most honest form, unity empowers communities, amplifies their voice, and ensures resilience in the face of adversity.

Unity only holds meaning when defined and acted upon. In political discourse, it manifests in two major ways:The first is unity among political fronts and movements. This form often fails when movements regard each other as threats rather than partners. The second is internal party cohesion. Here, unity is about presenting a united front to supporters, yet internal rifts frequently expose instability. Both are important, but neither can succeed without mutual respect and a clearly defined common cause.

What Unity Is Not

Unity is not conformity, nor is it the forced agreement on ideas, values, or goals. When everyone is expected to think and act the same, it stifles diversity and weakens the depth of experience and perspective that gives strength to a movement.

Unity is also not simply about being in the same place or forming coalitions— mere gatherings of people or coalitions or proximity alone does not create genuine connection. Real unity is an ongoing process of active engagement, honest struggle, and mutual support, all rooted in a common purpose.

Why Unity Remains a Constant Theme

Oromo history is marked by shared suffering and marginalization, which naturally fosters a longing for togetherness. The call for unity echoes not just through politics but also through cultural narratives. One childhood story, told and retold, illustrates this: a father gives each of his sons a stick to break—each break theirs easily. Then he gives them a bundle of sticks, and no one can break them. “Together,” he says, “no one can break you.” This story embodies the Oromo yearning for solidarity in the face of external threats.

Finding Common Ground and Commitment to the Common Cause

Despite tactical or even strategical differences, Oromo political movements share a commitment to self-governance, justice, and dignity. The question is whether they can align behind this shared vision. Different strategies, whether peaceful resistance or armed struggle—need not divide us if we agree on the destination. We need not think identical to work together; we need only commit to the same goal: self-governance, justice, and dignity.

Victory requires dedication from all sectors of Oromo society. We must reject divisions—regional, religious, or political that weaken our collective voice. Instead, we must protect our language, cultural institutions, and democratic values. Unity will not come from waiting but from committing ourselves fully to the task at hand. Only then can we claim ownership of our future.

Shared Identity and Struggle

The Oromo people are bound by more than just language or geography. Afaan Oromo serves as a powerful unifier, spoken across regions and religious lines. Oromo literature, cultural festivals like Irreecha, and foundations like the Gadaa system are the backbone of a collective identity that has survived despite systemic erasure. The oral tradition, Argaa-Dhageetti, continues to transmit values of equality and social harmony.

While the Oromo embrace diverse religious beliefs—Waaqeffannaa, Islam, and Christianity—they are united by a common worldview that emphasizes justice, community, and reverence for life. These shared spiritual and cultural values form the moral framework of the Oromo struggle.

Unity in Practice-Historical Continuity

From colonization to military rule, the Oromo have faced systematic marginalization. Land grabs, arbitrary arrests, cultural suppression, and political exclusion are not new.

The Oromo struggle for self-determination has been shaped by regional movements uniting diverse communities under shared aspirations. In Wollo-Raya, and Yejju, uprisings in the late 1920s and early 1930s resisted imperial taxation and central domination in unity. In 1936, the Western Oromo Confederation—comprising thirty-three leaders from western Oromia—petitioned the League of Nations for recognition under a British mandate, marking a significant early expression of Oromo unity Scribd. In Hararghe, the Arfaan Qallo movement, initiated in 1962, utilized music and literature to promote Oromo identity and resistance ResearchGate. Concurrently, the Bale Revolt (1963–1970) saw Oromo people unite against feudal oppression, laying the groundwork for modern Oromo nationalism.

Later, the Mecha-Tulama Self-Help Association (1963–1967) emerged as the first pan-Oromo movement, coordinating nationwide peaceful resistance and demonstrating the vitality of Oromo unity OPride.com. Together, these movements illustrate that Oromo unity was not merely an aspiration but a practical force—sustaining resistance, affirming identity, and paving the way for later organizations such as the Oromo Liberation Front. The Qeerroo and Qaarree movements, grassroots uprisings, and decades of resistance have forged a new generation that understands the value of unity not as submission, but as collective strength.

The Role of Oromo Women in Oromo Unity

Oromo women have been pivotal in fostering unity within their communities through cultural, social, and political engagement. Oromo women have long been central to the cohesion and resilience of their communities. They act as cultural guardians, preserving traditions, rituals, and oral histories that define Oromo identity. Through their participation in events like the Irreecha festival, women not only celebrate but also reinforce communal bonds and collective identity and a sense of shared heritage (Ethiopia Autonomous Media). Beyond culture, Oromo women make substantial economic contributions through farming, trade, and entrepreneurship, supporting families and local communities. Their economic involvement grants them influence in local decision-making and fosters unity by ensuring that community well-being is prioritized (allAfrica.com). Women in Oromo society also play key leadership roles, mediating disputes and promoting unity and peace within families and communities.

Traditional institutions such as Siinqee empower women to uphold social justice and protect the rights of the vulnerable, creating inclusive and harmonious communities. Oromo women have been at the forefront of political movements, advocating for the rights of their people and challenging oppressive systems. They have organized protests, participated in negotiations, and represented the Oromo cause on national and international platforms, demonstrating resilience and commitment to justice (Advocacy for Oromia). Their involvement demonstrates both courage and a commitment to justice, ensuring that the collective voice of the Oromo people is heard at local, national, and international levels (press.et).

The unity of the Oromo people, reinforced by the active participation of women, has had profound implications for regional politics in East Africa. In essence, the active participation of Oromo women ensures that unity within the community is not merely symbolic. Their leadership, activism, and cultural stewardship strengthen social cohesion and amplify the political influence of the Oromo people. Together, the cultural, social, and political unity of the Oromo community represents a powerful and transformative force in regional politics, demonstrating how grassroots cohesion can drive meaningful change at broader societal and governmental levels. The active participation and leadership of Oromo women in various spheres underscore their integral role in fostering unity and resilience within their communities.

From Purpose to Power

The future of Oromo unity lies not in speeches or slogans, but in purpose-driven solidarity. We must recognize our shared struggle, uphold our diverse identities, and commit to the common cause of freedom, democracy, and dignity. True unity requires that we stand together—not because we are the same, but because we believe in something greater than ourselves. Only then will we move from shared purpose to genuine solidarity.

The Power of Action

Unity must go beyond rhetoric. Each of us can contribute. In personal spaces, we must challenge divisive narratives and foster dialogue. In communities, we must mobilize, speak out, and support those marginalized. In our economic lives, we must back businesses and initiatives aligned with our values. And with our time, we must volunteer, organize, and participate in the building of a just society.

Closing Reflection:

The struggle for Oromo freedom and dignity cannot be carried by empty words or fragile alliances. It requires honesty, sacrifice, and the courage to place principle above personal gain. My late brother, Kumsa Burayu, lived and transitioned with this conviction. His legacy is a reminder that genuine solidarity is not an option but a necessity if our people are to secure justice and self-determination. To honor his memory, we must rise beyond the comfort of shallow unity and embrace the demanding but enduring strength of true solidarity.

About the Author: Dr. Worku Burayu is an Agronomist by profession; Steward of the Oromo causes by purpose. He is a committed advocate for justice, pluralism, and sustainable development in Oromia and beyond.

References

- A cultural representation of women in the Oromo society

- Advocacy for Oromia

- allAfrica.com

- Ethiopia: Vital Role of Women Among the Oromo People

Gadaa: An Indigenous Democracy of Oromo people on Promoting …

- Nordic Journal of African Studies

- Role of Oromo Women in Oromia’s Struggle for Freedom

Historic Achievement: Waaqeffannaa to Be Taught in Norwegian Secondary Schools

Bergen, Norway – In a landmark step for religious and cultural recognition, Waaqeffannaa, the indigenous faith of the Oromo people, has been officially included in Norway’s secondary school as part of religion and society education in school curriculum. This groundbreaking decision marks the first time Waaqeffannaa will be taught as part of the Religion and Society course, affirming its place among the world’s major religions.

Starting next week, students in Bergen will learn about Waaqeffannaa as a distinct and structured belief system. The Oromo community, both in Norway and worldwide, has welcomed this initiative with great pride, seeing it as long-overdue recognition of their spiritual heritage.

Waaqeffannaa is one of the oldest continuous religious traditions in the world, with a history spanning over 6,000 years. It is grounded in the worship of one God, Waaqa Tokkicha, and emphasizes values such as moral integrity (Safuu), peace (Nagaa), environmental stewardship, and social equality. Its teachings are conveyed through the Oromo language, enriching its cultural and linguistic significance.

This inclusion is the result of dedicated advocacy by community leaders and scholars who have worked tirelessly to document and promote Waaqeffannaa’s philosophy and practices. Their efforts ensure that both Oromo and non-Oromo students can now learn about a faith that champions harmony with nature and equality among people.

The introduction of Waaqeffannaa into formal education is more than an academic update—it is a celebration of identity and resilience. It offers a meaningful opportunity to elevate awareness of Oromo culture and history on a global stage.

As one community leader expressed, “This is only the beginning. We encourage all followers of Waaqeffannaa to take pride in this achievement and continue sharing the beauty and wisdom of our faith.”

This inspiring development opens new pathways for intercultural dialogue and understanding, reminding us of the rich diversity of human belief and the importance of honoring indigenous wisdom.

Celebrating Irreechaa: A Tradition of Gratitude

Long, long ago, nestled in the heart of Oromia, lived a wise old man named Oro. Every year, as the rainy season bid farewell and the land burst into vibrant green, Oro would climb atop the highest mountain. He would raise his hands to the sky and offer a heartfelt “Galatoomi Waaqaa!” – “Thank you, Waaqaa!” to the creator, for the blessings of rain, harvest, and life.

Oro’s gratitude became a tradition. His children, and their children after them, followed his example. They would gather by rivers and lakes, adorned in beautiful traditional clothes, singing songs of praise and offering gifts of flowers and fresh crops. This joyous celebration became known as Irreechaa – a time for thanksgiving, unity, and hope.

As generations passed, the Oromo people spread across the land, but they never forgot Oro’s tradition. Every September, they would journey to sacred places, especially to Finfinne, their capital city. There, by the shimmering waters, they would come together, a sea of colorful garments, to sing, dance, and offer their gratitude to Waaqaa.

Children would toss flowers into the water, their laughter echoing through the air. Elders would share stories of Oro and the importance of thankfulness. And as the sun set, painting the sky in hues of black, red and white, the Oromo people would feel a deep sense of connection to their history, their culture, and their God.

The end.

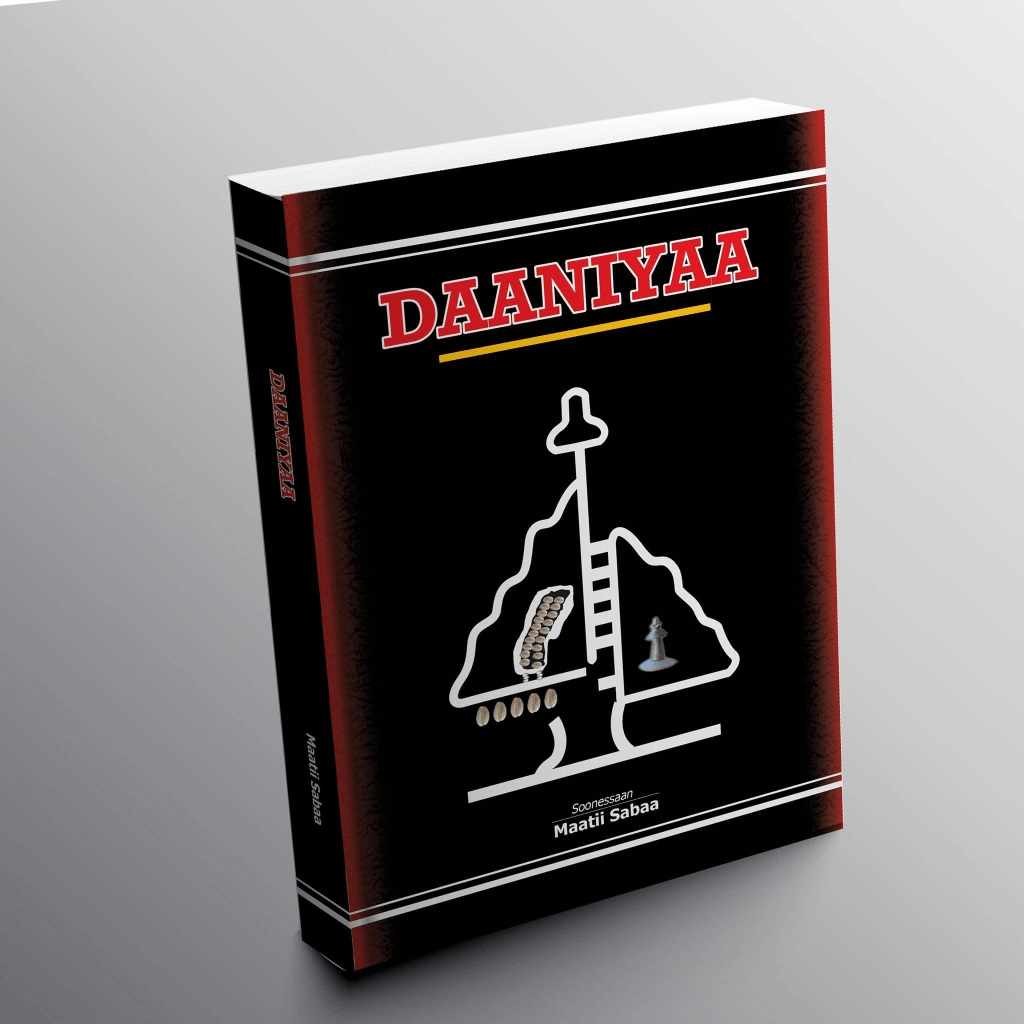

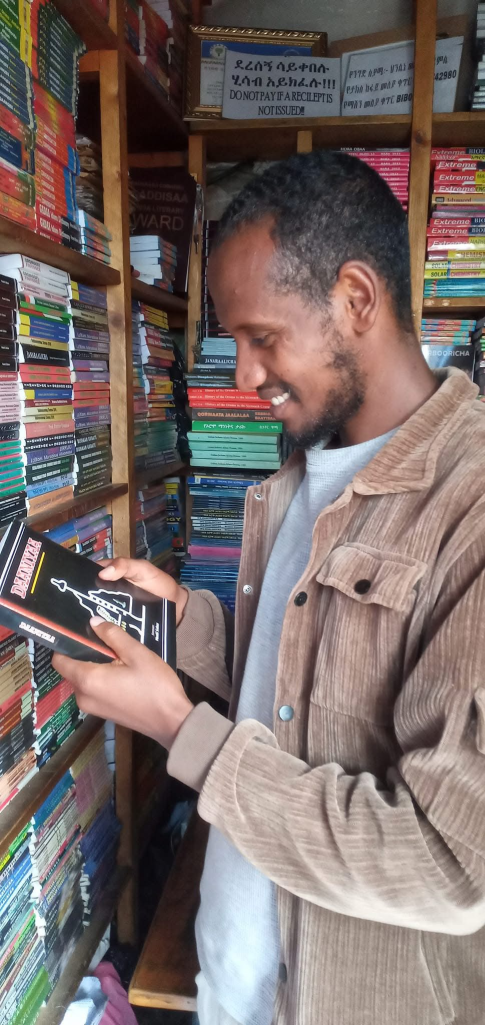

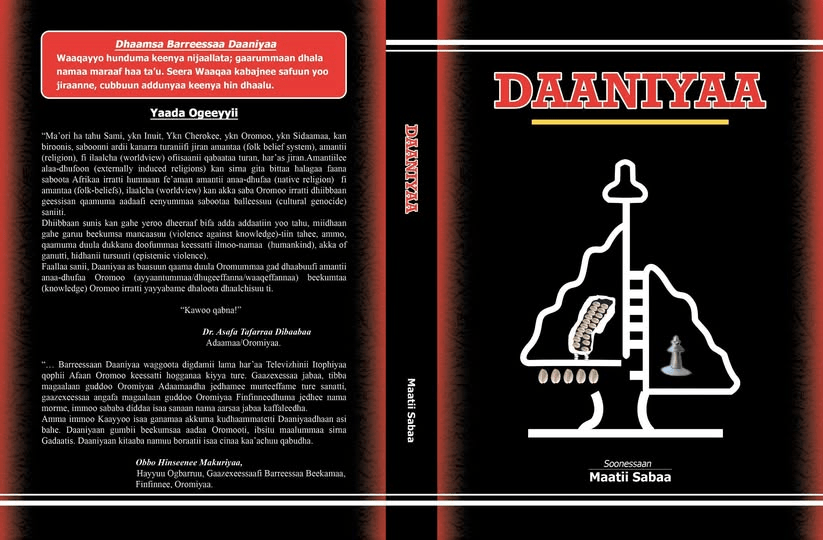

Daaniyaa: A Journey Through Oromo Spirituality and Culture

For generations, the wisdom of Waaqeffannaa—the ancient, monotheistic faith of the Oromo people—has been carried in the hearts and oral traditions of its adherents. Today, that wisdom finds its foundational voice in Daaniyaa.

This sacred text is a vital link to a spiritual heritage rooted in the reverence of Waaqayyo (the Supreme Creator), harmony with nature, and the moral principles of Safuu (moral and ethical order). It is an invitation to explore:

· Theological Depth: Understand the core principles of Waaqeffannaa, its view of the Creator, and the intricate relationship between humanity, the natural world, and the divine.

· Cultural Reclamation: Engage with a text that reaffirms a rich cultural identity, offering a powerful counter-narrative to historical erasure and a path for cultural preservation.

· Universal Spiritual Insights: Discover timeless teachings on peace, environmental stewardship, and community that resonate with global seekers of truth.

Daaniyaa is essential reading for the Oromo youth connecting with their roots, for elders preserving their legacy, for scholars documenting indigenous knowledge, and for anyone drawn to profound and authentic spiritual systems.

This is more than a publication; it is an act of preservation. Own a piece of living history. Discover the spiritual foundation of a nation.

Daaniyaa refers to the foundational written sacred text of Waaqeffannaa, the indigenous religion of the Oromo people. It serves to preserve Oromo culture and spirituality by documenting core beliefs in Waaqa Tokkicha (One God), moral principles like safuu (spiritual balance), and ancestral connections (Ayyaana). The text is crucial for religious identity, education, and promoting the Oromo language and heritage.

Celebrating Shanan: A Mother’s Festival in Oromo Culture

It is a special day for Sena Boka. Most of all, it is the day she had her first child, and for this she traditionally thanked God for helping her with members of the Oromo community mainly women who loved and respect Sena. She celebrated the Shanan with her friends in traditional Oromo beauty. The main purpose of Shanan is to encourage and bless the woman who gave birth on the fifth day. It is also a mother’s festival and a thanksgiving to God for helping her to give birth in peace. This is the day they celebrate the Shanan Day.

The rituals performed on this cultural ceremony have many benefits for the mother who has just recovered from childbirth. However, what is the essence of Shanan in Oromo culture? What are the benefits of this ceremony? What is done on this day? In this article we will try to look at the Shanan nature of things.

In Oromo culture, the shanan day (the fifth day after childbirth) is a deeply respected and cherished tradition. This day holds significant cultural, social, and emotional importance for the mother, the newborn, the family, and the community. It is a time of celebration, healing, and bonding, rooted in the values of care, support, and communal love.

The Shanan is an important and celebrated part of the midwife’s life. This is to the advantage of the family that a woman is safely released after carrying it in her womb for nine months. And the newborn is an addition to the family. Therefore, they do not leave a woman alone until she becomes stronger and self-reliant. Because it is said that the pit opens its mouth and waits for her. And when she goes to the bathroom, she carries an iron in her hand, and sucks it into her head.

This system plays an important role in helping the mother recover from labor pains. Family and friends who attend the Shanan will also encourage the midwife to look beautiful and earn the honor of midwifery. On this Shanan they made the midwife physically strong, socially beautiful, gracefully bright, and accustomed to the burdens of pregnancy and childbirth.

Why the Shanan Day? In the Oromo worldview, the number five holds special importance. The Gadaa system is organized around cycles of fives and multiples of five (e.g., five Gadaa grades, eight-year terms consisting of 5+3 years). Waiting for five days is a way to honor this cultural structure and to properly prepare for the important act of naming.

Key Aspects of Shanan:

Community Support:

The core of the Shanan tradition is the communal nature of Oromo society, where the well-being of the mother and child is a shared responsibility.

Blessings and Encouragement:

Community members gather to provide emotional support, motivation, and blessings to the mother, helping her regain strength and feel connected.

Marqaa Food:

The traditional food served on this day is marqaa. The serving of marqaa, a traditional food, is a central part of the celebration, symbolizing the care, blessings, and communal solidarity being extended to the new family. The midwives washed their genitals and ate together. Traditional songs of praise to God and encouragement of the mother are sung in turn.

Cultural Identity:

The ritual reinforces Oromo cultural identity and continuity, serving as a way to preserve and pass down these traditions to younger generations. During the ceremony, mothers dressed in traditional clothes surrounded the mother and expressed their happiness; sitting around the midwife after eating the marqaa, they blessed the new mother, ‘give birth again; carry it on your shoulder and back; be strong in your knees.’

Strengthening Bonds:

Shanan strengthens social and emotional bonds within the community, as everyone participates in welcoming the new member.

The celebration of the Shanan (fifth day) after a birth is a deeply significant and cherished ritual in Oromo culture, rooted in the Gadaa system. This culture has been weakened for centuries by various religious factors and the influence of foreign regimes. However, with the struggle of the Oromo people, the culture of encouraging childbirth is being revived and growing. Of course, many things may not be as perfect as they used to be. There is no doubt that the honor of Shanan as Sena Boka will contribute to the restoration of Shanan culture.

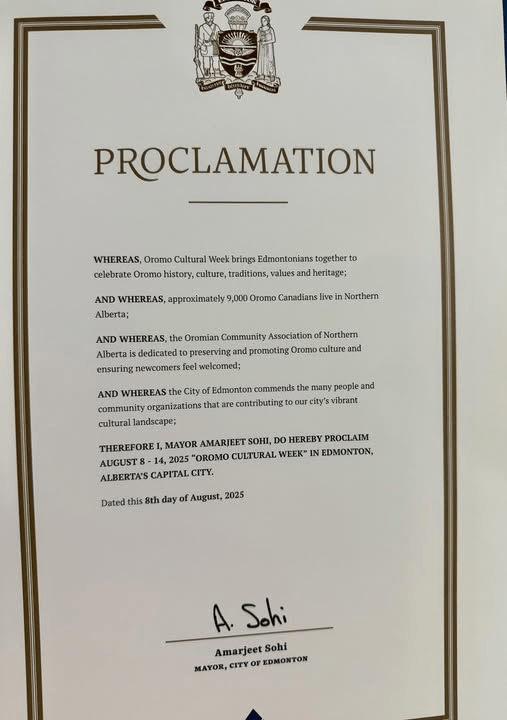

Oromo Cultural Week 2025: Celebrate Heritage in Edmonton

Oromo Cultural Week in Edmonton (August 8–14, 2025)

Celebrating Oromo Heritage, Unity & Resilience

📍 Location: Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

📅 Dates: August 8–14, 2025

🎉 Highlights: Traditional music, dance, art, history forums, and community feasts.

Expected Events & Activities

(Based on past Oromo cultural weeks in Canada; official schedule TBA)

1. Opening Ceremony (Aug 8)

- Speeches by Oromo elders & community leaders.

- Flag-raising (Oromo & Canadian flags).

- Traditional blessings (Waaqeffannaa prayers).

2. Cultural Showcase (Aug 9–10)

- Oromo Dance & Music: Dhaanto, Geerarsa, Shaggooyyee performances.

- Fashion Show: Traditional Horo Guduru attire and modern Oromo designs.

- Art Exhibition: Oromo paintings, crafts, and photography.

3. History & Identity Forum (Aug 11)

- Panel Discussions: Oromo history, Gadaa system, and diaspora experiences.

- Documentary Screenings: Films like “Oromo: The Forgotten People”.

4. Sports & Youth Day (Aug 12)

- Soccer Tournament: Oromo teams from across Canada.

- Poetry & Spoken Word: Young Oromo artists sharing their voices.

5. Community Feast (Aug 13)

- Oromo Cuisine: Injera, Waaddii (mariqaa), Buna Qalaa (coffee ceremony).

- Storytelling: Elders sharing oral histories.

6. Closing Celebration (Aug 14)

- Grand Concert: Oromo artists (local & international).

- Award Ceremony: Honoring community contributors.

How to Participate

✅ Attend: Open to all—Oromo community members & allies.

✅ Volunteer: Help with organizing (contact Oromo Canadian Community Association).

✅ Perform/Exhibit: Showcase your talent (music, art, poetry).

Organizers & Contacts

🔹 Oromo Canadian Community Association (OCCA)

🔹 Edmonton Oromo Youth Group

📩 Check Facebook/Eventbrite for official updates closer to the date.

Why This Matters

This week is a powerful way to:

- Preserve Oromo culture in the diaspora.

- Educate others about Oromo identity.

- Strengthen unity among Oromo Canadians.

“ Bilisummaa fi Walabummaa! “ (Freedom & Liberty!)

Need help finding specific details (e.g., venues, registration)? Let me know—I’m happy to dig deeper! 🌍💛

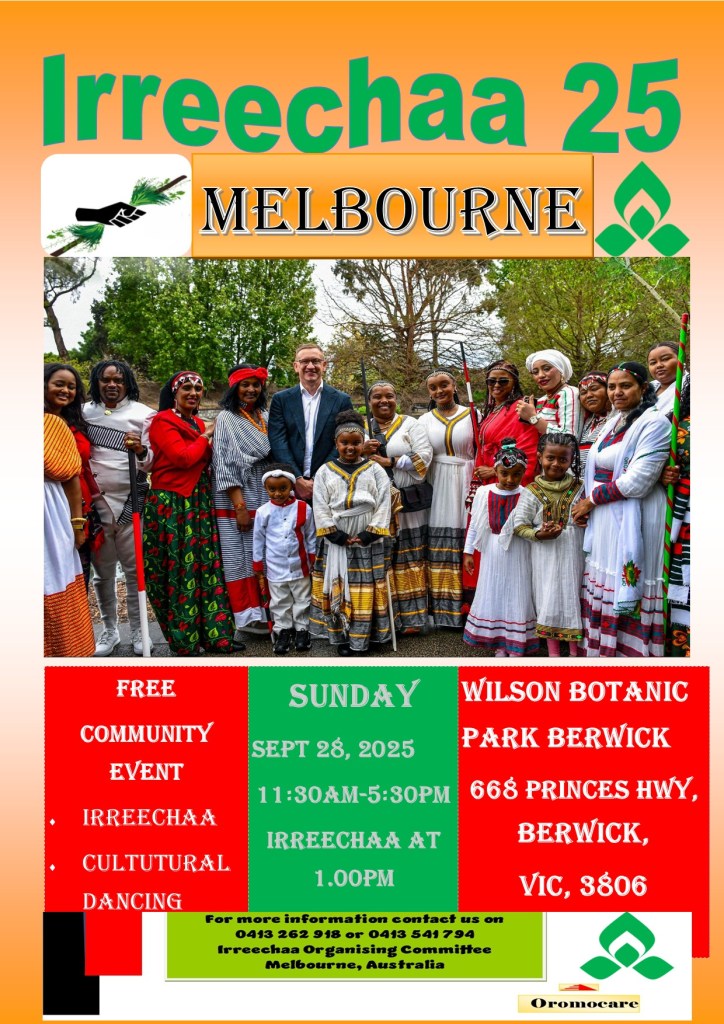

Irreechaa 25 Festival – Melbourne

Here’s a clear summary and important information for the **Irreechaa 25** event in Melbourne:

**Irreechaa 25 Festival – Melbourne**

* **Date:** Sunday, 28 September 2025

* **Time:** 11:30 AM to 5:30 PM

* **Location:** Wilson Botanic Garden

* **Address:** 668 Princes Hwy, Berwick VIC 3806

**Key Details:**

1. **Significance:** Irreechaa is the major **Oromo Thanksgiving Festival**, celebrating the end of the rainy season, blessings of the past year, and welcoming the new spring season (in the Southern Hemisphere context, it aligns with the end of winter/start of spring). This marks the **25th anniversary** of Irreechaa celebrations in Melbourne.

2. **Venue:** Wilson Botanic Garden in Berwick is a beautiful and spacious public park, well-suited for large cultural gatherings like this.

3. **What to Expect:**

* Traditional Oromo prayers, songs, and speeches.

* Cultural performances including music and dance (like the *Shaggooyyee*).

* Community gathering and socializing.

* Traditional Oromo attire is often worn.

* Food and refreshments (likely available for purchase from vendors).

* A vibrant and family-friendly atmosphere celebrating Oromo culture and heritage.

**Practical Information:**

* **Transportation:**

* **Public Transport:** Take a train to **Berwick Station** (on the Pakenham line). From the station, it’s about a 15-20 minute walk (1.3 km) to the Garden entrance. Local buses also serve the area near the highway – check the PTV app/website for routes like 828, 830, 835, or 836 stopping near the Garden.

* **Parking:** Limited free parking is available within Wilson Botanic Garden, and street parking is available on surrounding roads. **Arrive early as parking can fill up quickly for large events.**

* **What to Bring:**

* Comfortable shoes (the Garden has walking paths).

* Sun protection (hat, sunscreen) or rain gear (Melbourne weather can be changeable in September).

* A blanket or picnic rug for sitting on the grass.

* Water bottle.

* Cash might be useful for smaller vendors, though card facilities are increasingly common.

* **Accessibility:** Wilson Botanic Garden has accessible paths and facilities. Check specific event details closer to the date for any accessibility services provided by the organizers.

**For the Most Up-to-Date Information:**

It’s always wise to check official sources or community social media pages closer to the event. Look for pages associated with the **Oromo Community Association in Victoria** or similar groups.

This is a wonderful opportunity to experience the rich culture and traditions of the Oromo community in Melbourne. Enjoy the celebrations!

Conservation Ambitions: Ethiopia Plants 700 Million Trees

ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia (AP) — Ethiopia launched a national campaign on Thursday to plant 700 million trees in one day as part of an ambitious conservation initiative that aims to plant 50 billion trees by 2026.

The reforestation campaign has been a personal project of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed since 2019.

Tesfahun Gobezay, state minister for the Ethiopian Government Communication Services, told reporters before 6 a.m. local time that some 355 million seedlings had already been planted by 14.9 million Ethiopians.

It was not possible to verify the government’s figures. Ethiopia has a population of more than 120 million people.

“We kicked off this year’s one-day green Legacy planting early this morning,” Abiy said on social media platform X. “Our goal for the 7th year is 700 million seedlings. Let’s achieve it together.”

Authorities say some 40 billion tree seedlings have been planted since 2019. The target for 2025 is 7.5 billion trees.

Abiy took power in 2018 as a reformist. He won the Nobel Peace Prize for making peace with neighboring Eritrea but a war that erupted shortly afterward in the Ethiopian region of Tigray damaged his reputation as a peacemaker. He now he faces another rebellious uprising in the Amhara region.

Many public offices are closed Thursday to make time for tree planting. Thousands of public servants have been dispatched across the east African nation to help plant seedlings made available through the official bureaucracy.

At the break of dawn, many were seen planting trees in the capital Addis Ababa. At a site in Jifara Ber dozens of people were involved, including children.

Almaz Tadu, a 72-year-old grandmother, brought her grandchildren to a tree planting event she said reunites her with neighbors.

“I have come with my mother and this is my third time planting trees,” said 13-year-old student Nathenael Behailu. “I dream of seeing a green environment for my country.”

Another Addis Ababa resident, Ayanaw Asrat, said he has heeded the call for the last three years. “I came early and I have so far planted 15 seedlings. I am very happy to contribute to creating greener areas across Addis,” he said.

Abiy himself was active in Jimma, the largest city in the southwestern region of Oromia. Cabinet ministers were sent to other regions to support local officials.

Kitessa Hundera, a forest ecologist at Jimma University, told The Associated Press that a “noble” reforestation initiative was being carried out by non-experts who could not define conservation objectives regarding site selection and other technical issues.

He cited concern over mixing exotic species with indigenous ones and the apparent failure to report the survival rate of seedlings planted over the years. He also doubted it was possible to plant 700 million seedlings in one day.

“Planting 700 million seedlings in one day needs the participation of about 35 million people, each planting 20 seedlings, which is practically impossible,” he said.

Building a Sovereign Nation: The Oromo Path to Stability

By By Bantii Qixxeessaa

A common argument raised against the Oromo liberation struggle for independence is this:“Even if Oromia becomes independent, how do we know it won’t end up like South Sudan, Eritrea, or Somalia—mired in authoritarianism, internal conflict, or state collapse?”This is a sobering question. It deserves more than a dismissal. It demands reflection, honesty, and a credible roadmap.There is truth in the concern. History confirms that independence alone does not guarantee peace, freedom, or democracy. There is truth in the concern. History confirms that independence alone does not guarantee peace, freedom, or democracy. South Sudan gained independence in 2011 after a long and bloody struggle, only to descend into civil war and political dysfunction.

Eritrea fought heroically for sovereignty, only to replace foreign domination with domestic repression. Somalia collapsed into stateless chaos after the fall of its authoritarian regime. In all three cases, the post-independence vision was either unclear, co-opted, or completely abandoned.

But this is only one side of the story.

There are also powerful examples of nations that won independence and successfully built stable, democratic, and sovereign states. Timor-Leste, after decades of brutal occupation, transitioned into a pluralistic democracy with repeated peaceful elections. Namibia emerged from South African apartheid rule to become one of Africa’s most stable democracies. Slovenia, which broke away from Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, managed a peaceful transition and integrated swiftly into the European Union. Botswana – Maintained multiparty democracy and rule of law since 1966. Cape Verde – Peacefully transitioned to multiparty democracy and maintained political stability. India – Despite enormous diversity and challenges, India preserved electoral democracy since independence. These cases, and others not mentioned here, remind us that independence, when coupled with visionary leadership, institution-building, and inclusive governance, can yield not only sovereignty—but peace, democracy, and prosperity.

The point is clear: independence is not a guarantee of success, but neither is it a path to inevitable failure. The outcomes depend on preparation, political culture, and strategic execution.

So the question is not whether independence is worth pursuing, but whether we are willing to do the hard work to ensure it leads to a just and thriving Oromia. For Oromia, the lesson is not to be discouraged by the odds, but to be disciplined by them. The struggle must not end with independence, it must start with building the foundations of the state we want to live in.

Independence Alone Does Not Guarantee Peace, Freedom, or Democracy

The Oromo struggle is not merely about redrawing borders. It is about reclaiming power from an empire that has long denied the Oromo people the right to govern themselves. That goal will only be fulfilled when the new Oromia is built on justice, freedom, and democratic accountability.

The failure of other post-independence states was not that they chose sovereignty, but that they did not adequately plan what to do with it once they had it. For them Independence became an endpoint instead of a beginning. Oromia must learn from their experience.

What Went Wrong with these movement, later states? Here as some Key Lessons.

- Lack of Political Consensus: South Sudan’s liberation forces fractured along ethnic (the Dinka and the Nuer) and personal rivalries (Salva Kiir Mayardit and Riek Machar) after independence. Their unity was wartime-deep but not nation-deep.

- Weak Institutions: Eritrea’s government was centralized around a single figure, Isaias Afwerki. In the absence of independent institutions, authoritarianism became inevitable. The concentration of power in one leader, the failure to implement a democratic transition after independence, the systematic suppression of dissent, the militarization of governance, and the entrenchment of one-party rule without internal accountability made authoritarianism not just likely—but the logical outcome.

- Militarization of Politics: In both South Sudan and Eritrea, there was no planned and inclusive transition to civilian-led, democratic governance. Instead, armed movements transitioned into ruling elites without civilian oversight, perpetuating a culture of command over consent.

- Failure to Transition from Liberation to Governance: If a liberation movement is undemocratic in its internal organization and decision-making during the struggle, it is likely to reproduce those same authoritarian habits once it comes to power. In both the South Sudanese and Eritrean liberation struggles, the movements failed to democratize internally and instead carried autocratic tendencies into statehood.

- Neglect of Reconciliation and Inclusion: Neither South Sudan nor Eritrea implemented meaningful, independent truth, reconciliation, or justice commissions after achieving independence. The absence of such mechanisms played a significant role in their post-liberation crises.Somalia’s fragmentation was deepened by the exclusion of key clans and groups, undermining the legitimacy of national institutions.

- No Economic Vision: Liberation without economic development leads to frustration, elite capture, and failed expectations. neither South Sudan nor Eritrea had well-developed or realistic economic development plans when they gained independence. This absence of clear, inclusive, and sustainable economic strategies significantly contributed to post-independence frustration, elite capture, and ultimately state failure or stagnation.

How Can the Oromo Movement Avoid These pitfalls?

- Start Nation-Building Before Statehood: Nation-building must begin during the struggle—not after victory. This means cultivating democratic norms, inclusive leadership, institutional habits, and a shared civic vision now, so Oromia rises not just as a state, but as a nation rooted in justice, dignity, and self-rule.

We can begin this process by:

a. Democratizing the Movement Itself: Hold inclusive consultations across Oromo political organizations. Practice internal democracy—rotate leadership, hold free elections, and foster open debate without branding dissent as betrayal. A democratic state cannot emerge from undemocratic movements.

b. Developing a Shared Vision: Draft a People’s Charter or “Oromo Covenant” through public forums that articulates the future state’s core values (democracy, justice, equality), defines citizen rights and responsibilities, and establishes unifying symbols and narratives.

c. Building and Strengthen Oromo Institutions: Create shadow institutions like diaspora parliaments, advisory councils, and grassroots dispute-resolution platforms. Launch Oromo think tanks and development organizations to shape post-independence governance. Sustainable nations rely on institutions—not just leaders.

d. Drafting a Transitional Roadmap: Prepare a clear, inclusive plan for transferring power post-independence. Include a transitional charter, a timeline for elections, constitution-making, and institution-building. Planning now prevents chaos later. Such planning helps prevent power grabs and chaotic improvisation during a fragile transition.

e. Modeling Inclusive Leadership and Conflict Resolution: Initiate dialogues among Oromos across regions, religions, and political lines to build trust and reconciliation. Use traditional Oromo mechanisms (e.g., Gadaa) and modern legal norms to manage disputes. Promote leaders guided by integrity, not allegiance. Independence cannot bring stability without reconciliation and trust.

- Ensure Civilian Supremacy: Armed resistance must not give rise to a ruling military caste. Civilian political authority must guide Oromia’s future. If the Oromo liberation movement seeks to build a just and democratic state, it must begin now to ensure that guns return to the barracks—and governance rests with the people through ballots, not bullets. Civilian supremacy—the principle that elected or accountable civilian leadership controls the military—is essential to preventing post-independence authoritarianism. To uphold this principle, the movement must take deliberate steps during the struggle to clearly define and separate military and political roles.

- Forge a National Covenant: Develop a pre-independence social contract that binds Oromo regions, parties, and communities together in shared purpose. Forging a National Covenant is a strategic and unifying step that helps consolidate internal cohesion, articulate a collective vision, and lay the foundation for inclusive governance after independence. It transforms aspiration into agreement, agreement into accountability, and accountability into a shared destiny. The Covenant offers a moral foundation and unifying framework that can endure political transitions and guide the creation of a democratic Oromia. By ensuring all major segments of Oromo society have a stake in it, the Covenant becomes both a political backbone and a public promise. Embedded in the movement’s strategy, it serves as the compass for nation-building—before and after independence.

- Guarantee Inclusivity for All Peoples: Oromia will be home to non-Oromo minorities, and any future vision must ensure their protection and full citizenship. Guaranteeing inclusivity—especially for non-Oromo communities—is both a moral imperative and a strategic necessity for legitimacy, stability, and democratic state-building. This is not a concession; it is a declaration of confidence in a democratic future. By ensuring that all residents feel a genuine sense of belonging, the Oromo movement lays the foundation for a stronger, more unified, and enduring nation.

- Prepare a Transitional Charter and Leadership Framework: Governance must not be improvised. A clear roadmap for the first five years—outlining institutions, timelines, elections, and reforms—is essential. Preparing a Transitional Charter and Leadership Framework ensures that post-independence Oromia is not vulnerable to instability, power struggles, or elite capture. It signals maturity, foresight, and credibility—both to the Oromo people and the international community. Such a framework provides the structure, stability, and legitimacy Oromia will need during its most fragile moment: immediately after independence. States should not be improvised—they must be deliberately designed.

- Establish a Truth and Justice Commission: Addressing historical wounds through transparent, accountable processes is essential for justice and healing—not revenge. A Truth and Justice Commission (TJC) is vital for legitimacy and nation-building, especially in Oromia, where the people have endured decades of systemic violence, dispossession, and betrayal. Crucially, the groundwork for such a commission must be laid before independence to ensure swift and credible implementation afterward. Truth and justice must not wait—they must be integral to the liberation itself. By planning now, the Oromo movement demonstrates that it seeks not just power, but moral legitimacy and national healing. In doing so, it breaks the cycle of revenge and paves the way for a democratic future rooted in memory, accountability, and reconciliation.

- Develop Economic Sovereignty: Plan now for food security, youth employment, regional trade, and resource equity, so that political independence translates into real, lived freedom. Economic sovereignty is essential to ensuring that Oromia’s future is not symbolic but substantive. True sovereignty is not just a flag or a border, it is the ability to feed, employ, and empower your people. Building the foundations of a dignified life must be central to the liberation struggle. The Oromo movement must treat economic development not as a post-independence task, but as a core pillar of liberation itself.

The Cost of Caution vs. the Risk of Action

Opponents of independence argue that avoiding these risks is reason enough to remain under the Ethiopian so called federation. But Ethiopia’s own record is one of repression, fragmentation, and crisis. Remaining in the current system is not a guarantee of peace or prosperity, it is a guarantee of stagnation, dependency, and continued repression and subjugation.

The Oromo people are not doomed to repeat the mistakes of others. But they must learn from them, seriously, humbly, and strategically. The goal is not just a new flag. It is a new political culture, rooted in the principles the Oromo struggle has long proclaimed: freedom, equality, justice, and self-rule.

Independence is only the first chapter—but without it, the rest of the story cannot be written.

Opponents of Oromo independence often argue that its advocates are fixated on symbols—new flags, new borders—without a plan for what comes next. Nothing could be further from the truth. The call for independence is not about retreating into nationalism; it is about unlocking the possibility of justice, peace, democracy, and dignity—none of which have ever been guaranteed under the current imperial structure.

The reality is this: for the Oromo people, there can be no meaningful next chapter without the first one. There can be no justice without sovereignty. No peace without self-rule. No democracy without the freedom to determine our own future. Independence is not the end goal—it is the beginning of a better path. The Oromo movement must and does look beyond independence, but it also recognizes that independence is the necessary foundation on which every future reform must rest.

We are not asking for isolation. We are demanding inclusion—on our own terms, in our own voice, in our own land.

(Published as part of the “Oromia Rising: Essays on Freedom and the Future” series. Everyone is invited to contribute. Send your contributions to bantii.qixxeessaa@gmail.com.)

Oromo Indigenous Knowledge: Smart Erosion Solutions for Ethiopia

Why scientists are turning to Oromo indigenous knowledge for erosion solutions?

Scientists are increasingly turning to Oromo Indigenous Knowledge (IK) for erosion solutions, particularly in the Ethiopian highlands, due to several compelling reasons:

1. **Severity of Erosion in Oromo Lands:** The Ethiopian highlands, home to a large Oromo population, are among the world’s most erosion-prone regions. Decades of deforestation, population pressure, intensive agriculture on slopes, and climate change impacts have caused catastrophic soil loss, threatening food security, water resources, and livelihoods. Conventional approaches alone haven’t sufficed.

2. **Limitations of Conventional Solutions:**

* **Cost & Scalability:** Large-scale engineering solutions (like extensive terracing or dams) are often prohibitively expensive and difficult to implement and maintain over vast areas.

* **Top-Down Approach:** Imported technical solutions sometimes fail to consider local ecological specificity, social structures, and economic realities, leading to poor adoption or abandonment.

* **Sustainability:** Some conventional methods may rely heavily on external inputs or lack long-term ecological integration.

3. **Strengths of Oromo Indigenous Knowledge (QBS – *Qaalluu*, *Baayyee*, *Safuu*):** Oromo environmental knowledge, often guided by the philosophy of *Qaalluu* (spiritual connection/balance), *Baayyee* (diversity/abundance), and *Safuu* (moral/ecological order), offers proven, context-specific solutions:

* **Holistic Land Management:** The *QBS* system integrates crops, trees, livestock, and social structures. Practices are interconnected, supporting each other and the overall ecosystem health.

* **Time-Tested & Locally Adapted:** IK has evolved over centuries *in situ*, making it uniquely adapted to local soils, climates, topography, and biodiversity. Its persistence proves its effectiveness under local conditions.

* **Effective Specific Practices:**

* **Agroforestry & Multipurpose Trees:** Integrating native trees (e.g., *Cordia africana* – Waddeessa, *Croton macrostachyus* – Bakkanniisaa) for shade, fodder, fuel, soil improvement, and **root systems that bind soil**.

* **Mixed Cropping & Intercropping:** Planting diverse crops together (e.g., cereals with legumes or root crops) provides better ground cover year-round, reducing splash erosion and improving soil structure.

* **Contour Farming & Natural Terracing:** Planting along contours and using specific grasses/shrubs on terrace edges (*Furrii* or *Garbii*) to stabilize them effectively.

* **Crop Residue Management:** Leaving crop residues (*Eebba*) as mulch protects the soil surface from raindrop impact, reduces runoff, conserves moisture, and adds organic matter.

* **Rotational Grazing & Livestock Integration:** Controlled grazing prevents overgrazing, while manure application improves soil fertility and structure. Specific grasses (*Gorii*) are promoted for erosion control on slopes.

* **Micro-Catchments & Water Harvesting:** Traditional techniques like *Targa* (small pits) and *Doyyoo* (micro-basins) capture runoff, allowing water to infiltrate and reducing erosive flow.

* **Sacred Groves & Community Forests:** Protected areas (*Odaa*, *Gudaa*) conserve biodiversity, stabilize slopes, regulate water flow, and serve as repositories of indigenous knowledge.

* **Cost-Effectiveness & Accessibility:** IK relies primarily on locally available materials, labor, and knowledge, making it far more affordable and accessible for local communities.

* **Community Ownership & Social Capital:** IK is embedded in community structures, norms, and governance systems (like the *Gadaa* system). This fosters strong community ownership, participation, and long-term maintenance of conservation measures.

* **Sustainability & Resilience:** Oromo IK emphasizes maintaining ecological balance and diversity, leading to inherently more resilient and sustainable land management systems.

4. **The Shift Towards Participatory & Integrated Approaches:**

* **Recognition of IK Value:** Scientists increasingly acknowledge that IK offers invaluable insights and practical, sustainable solutions often overlooked by purely technical approaches.

* **Co-Production of Knowledge:** The trend is towards collaborative research where scientists work *with* Oromo communities to document, understand, scientifically validate, and refine IK practices. This respects local expertise and ensures solutions are culturally appropriate and readily adopted.

* **Hybrid Solutions:** Combining the strengths of IK (local adaptation, cost-effectiveness, social integration) with relevant scientific innovations (precise mapping, improved plant varieties, targeted engineering) creates more robust and effective erosion control strategies. For example, scientific validation of the effectiveness of specific native plants used in bund stabilization.

* **Policy Shifts:** International frameworks (like CBD, UNCCD) and national policies increasingly emphasize the importance of integrating IK into sustainable development and environmental management.

5. **Addressing Climate Change:** IK systems, developed to cope with variability, offer valuable strategies for building resilience to climate change impacts like increased rainfall intensity and droughts, which exacerbate erosion.

**Challenges in Integration:**

* **Documentation:** Much IK is oral and localized, requiring careful, respectful documentation.

* **Validation & Understanding:** Scientific research is needed to understand *why* and *how* some practices work so effectively.

* **Power Dynamics:** Ensuring equitable partnerships where communities are genuine co-researchers and benefit equitably from any outcomes or commercialization.

* **Changing Contexts:** Adapting IK to rapidly changing social, economic, and climatic conditions while preserving its core principles.

**In essence, scientists are turning to Oromo IK because it provides a treasure trove of proven, sustainable, cost-effective, and culturally grounded erosion control practices. Integrating this deep local wisdom with scientific knowledge offers the most promising pathway towards tackling the severe land degradation challenges in Oromo territories and similar regions.** It represents a move towards more holistic, participatory, and ecologically sound land management.