Barak Mountain’s Irreechaa: A Spiritual Gathering for Peace and Gratitude

From the Highlands, a Prayer of Gratitude: Irreechaa Tulluu Unites Community on Barak Mountain

SANDAFAA BAKKEE, OROMIA – As the first light of the autumn sun crests the horizon, the slopes of Barak Mountain are already a tapestry of movement and color. Thousands of men, women, and children, dressed in the brilliant whites and intricate embroideries of traditional Oromo attire, ascend the paths in a serene, purposeful procession. They are not mere hikers; they are participants in one of humanity’s oldest and most profound rituals: offering thanks to the divine for life’s sustenance and praying for peace in the seasons to come. This is Irreechaa Tulluu, the hill festival, and on this day, Barak Mountain is its sacred stage.

Irreechaa is not a single event but a bi-annual dialogue with nature, deeply embedded in the Gadaa system’s ecological wisdom. The first, Irreechaa Arfaasaa, celebrated at riversides in early October, welcomes the rainy season—a festival of renewal, cleansing, and thanksgiving for the promise of life. The second, unfolding now in the crisp autumn air, is Irreechaa Tulluu. As the harvest is gathered, the community climbs to the high places, turning gratitude into a physical act of ascent, symbolizing a spiritual upliftment and a reflective review of the passing year.

This season, the community of Sandaafaa Bakkee has transformed Barak Mountain into a breathtaking open-air temple. Led by revered elders, or Hayyus, who carry staffs of authority and centuries of tradition, the people climb. The air fills with the sound of communal prayer, traditional Geerarsa (praisesongs), and the soft murmur of individual supplications. At the summit, the focal point is not an altar of stone, but a shared spiritual intention. Participants bring fresh green grasses and flowers, symbols of peace and prosperity, offering them as tokens of gratitude to Waaqaa (the Creator) for the blessings of the past year and as prayers for harmony and abundance in the next.

“This mountain is our church, our mosque, our most sacred space,” explained Elder Gammachuu Roba, pausing during the ascent. “When we climb together—young and old, from all walks—we are doing more than celebrating. We are reaffirming our bond with Waaqaa, with our ancestors, and with each other. We pray for nagaa (peace) because without peace in our hearts, our communities, and our environment, no prosperity can take root.”

Beyond its profound spiritual core, Irreechaa Tulluu is a vibrant celebration of Oromo identity. The mountain slopes become a living museum of culture. The air resonates with the rhythms of the kebero drum and the strings of the kirar. Young men engage in spirited waa’ee (verbal jousting), showcasing wit and wisdom, while circles form for traditional dance. It is a powerful, collective assertion of a culture that has endured, adapted, and thrived.

For observers and visitors, the festival offers an unparalleled immersion into the “timeless richness of Oromo culture,” as promoted by the Oromia Tourism Bureau. It is a chance to witness a living tradition where faith, ecology, and community are seamlessly woven together. As the sun sets on Barak Mountain, casting long shadows over the departing crowds, the feeling left behind is one of collective catharsis and renewed hope. The prayers for peace, whispered from the highlands, are carried on the wind, a timeless echo from a people forever rooted in their land and their gratitude.

#Irreechaa #IrreechaaTulluu #OromoCulture #BarakMountain #Oromia #LandOfOrigins #Ethiopia #CulturalHeritage

Oromo Diaspora: Celebrating the Legacy of the Maccaa-Tuulamaa Association

From Cairo to the Heart of Oromia: The Maccaa-Tuulamaa Association’s Enduring Flame

Cairo, Egypt – In a vibrant hall far from the verdant highlands of Oromia, the air was thick not with desert dust, but with the palpable weight of memory and the steady pulse of resilience. Last week, the Oromo community in Egypt gathered not for a simple social event, but for a profound act of collective remembrance: the 7th anniversary celebration of the founding of their chapter of the Maccaa-Tuulamaa Association (MTA).

This was more than a milestone marked on a calendar. It was a deliberate and powerful reaffirmation of an identity that refuses to be fragmented by geography. The speeches given were not mere formalities; they were carefully woven threads in the ongoing tapestry of Oromo history, reminding all present that the story of the Maccaa-Tuulamaa Association is inextricable from the modern narrative of the Oromo struggle itself.

For the uninitiated, the significance of such a gathering in a place like Cairo might be lost. But to understand the MTA is to understand a cornerstone of 20th-century Oromo political consciousness. Founded in 1963, the association emerged not as a militant front, but as a critical socio-cultural and intellectual awakening. At a time when the very fabric of Oromo identity was under systemic pressure, the MTA provided a legitimate, organized platform. It championed education, preserved language and history, and most importantly, fostered a sense of unified nationhood (sabboonummaa) among the Oromo people. It was the seed from which more overt political movements would later grow, making its founders not just community organizers, but architects of a modern political identity.

Therefore, the anniversary in Cairo transcends a chapter meeting. It represents a vital dialectic of diaspora existence: the act of building a future in one land while being steadfast custodians of a past from another. The community in Egypt, like Oromo diasporas worldwide, lives this duality. They build careers, raise families, and navigate life in Egypt, all while tending a flame ignited generations ago in the heart of Oromia. The detailed recounting of the MTA’s history at the event was a sacred ritual of passing this torch, ensuring that younger generations born on the Nile understand their roots in the Gibe River valley.

The calls for unity (tokkummaa) issued from the podium in Cairo resonate with a particular urgency today. They speak to challenges both internal and external. The diaspora, while a source of immense strength and resources, is not immune to the political and social fissures that affect any global community. The anniversary serves as an annual calibration—a reminder that the foundational principles of the MTA were unity, self-reliance, and the uplifting of the Oromo people as a whole. It is a call to look beyond differences and focus on the foundational hundee (root) that connects them all.

Furthermore, this gathering is a subtle but clear statement of unbroken continuity. It signals that the spirit of the MTA, the spirit of organized, dignified, and persistent advocacy for Oromo rights and identity, is not confined by borders or diminished by time. Whether in Cairo, Minneapolis, or Melbourne, the association’s legacy provides a framework for community cohesion and purpose. It answers the poignant question of how to remain meaningfully connected to a homeland many cannot safely return to. The answer lies in being living archives, active advocates, and unwavering supporters.

As the celebrations concluded, the message was clear: the Maccaa-Tuulamaa Association is far more than a historical relic. It is a living institution, its meaning continually renewed by diasporas like the one in Egypt. Their anniversary was a declaration that the seeds planted by the founders in the 1960s have borne fruit that now grows in global soil. It affirmed that the duty of the present generation is not just to remember the past, but to nurture this resilient tree, ensuring its branches—spread across the world—remain strong, interconnected, and forever reaching toward the light of justice and self-determination for Oromia.

Remembering the Past: Key to Oromo Self-Determination

Feature Commentary: On History, Fear, and the Unfinished Work of Liberation

By Maatii Sabaa

February 1, 2026

A specter haunts the discourse around the Oromo struggle for self-determination: the fear of history. Not the fear of making history, but the fear of speaking its full, unvarnished truth. A persistent notion suggests that to revisit the complex, often painful narrative of the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) is to court chaos, to sow discord, and ultimately, to abandon the ongoing struggle. This perspective, often implied if not directly stated, holds that dwelling on the past is counterproductive.

This is a profound and dangerous miscalculation.

To argue that examining our history—with all its sacrifices, schisms, and strategic crossroads—has no place in the current struggle is to build our future on a foundation of amnesia. It is to disrespect the very martyrs in whose name we claim to act. The journey of the OLF, from its intellectual germination in the early 1970s, its formal establishment in 1973, and the articulation of its political program in 1976, is not a relic to be shelved. It is the origin story of a modern political consciousness. The subsequent decades of immense sacrifice—of targeted killings, imprisonment, and exile of its intellectuals and heroes—were the bloody ink with which chapters of resistance were written. The bittersweet victory of 1991, which broke the back of the Derg but saw the dream of Oromo liberation deferred, is a pivot point every contemporary analysis must contend with.

The internal fractures, the political alliances within the four-party coalition of 1991, the subsequent marginalization, and the difficult choices faced in the 1990s are not scandalous secrets. They are critical data points. They explain why the OLF found itself back in the bushes, in a “no-choice” scenario, fighting to keep a promise made to its fallen. To ignore this is to ignore the root causes of the very cycles of conflict and resistance that have characterized the past thirty years.

The claim that today’s generation, which has demonstrated formidable political maturity through movements like the #OromoProtests (Finfinnee DFS/Gadaa system is not the correct term here, replaced with the widely recognized hashtag) and the Qeerroo mobilization, would be destabilized by an honest reckoning with history is an insult to their intelligence. It is a paternalistic logic that assumes they cannot handle the complexity that shaped their present. We see remnants of old guard mentalities attempting to replay 30-year-old scripts, causing needless friction, and we are told to look away for the sake of unity. But unity forged in silence is fragile; unity built on a shared, honest understanding is unbreakable.

Therefore, speaking our history—the full history of a people’s resistance against successive repressive systems—is not separate from the struggle. It is an essential organ of it. Our history is our primary weapon against systemic alienation. When we surrender its narrative out of fear, we disarm ourselves intellectually and spiritually.

The central question for every individual invested in this cause today must not be, “How do I avoid offending powerful sensibilities?” It must be: “What is my role in ensuring the ultimate sacrifice of our heroes was not in vain?” For those who mistake gossip, character assassination, and sowing despair among the ranks as revolutionary action, a reckoning is due. True revolutionary duty lies in disciplined organization, in studying and adapting the strategic frameworks of our forebears to today’s realities, and in building upon—not abandoning—their foundational goals.

My recounting of history is not a wish to return to yesterday. It is an act of gathering all the pieces of our story so we can understand the puzzle of our present. Yes, we must celebrate every hard-won gain at the national level. But we must also be clear-eyed: without a deliberate, collective, and honest effort to address the core, unresolved question of Oromo national self-determination, those gains will remain incomplete and vulnerable.

The final struggle is not just against a visible enemy; it is against the forgetting, the fear, and the fragmentation of our own story. To remember completely, to analyze courageously, and to speak truthfully is, itself, a revolutionary act.

The Final Struggle is to End Subjugation!

Victory for the Oromo People!

Restoring Haramaya: A New Era for Tourism and Environment

Feature Commentary: Haramaya’s Return – From Symbol of Loss to Engine of Growth

For years, the name Haramaya evoked a profound sense of loss and environmental grief in Ethiopia. The haunting image of a vast, cracked lakebed where a major body of water once thrived became a national symbol of ecological mismanagement and the devastating consequences of environmental neglect. The primary culprit, as experts consistently pointed out, was siltation and pollution—a slow-motion disaster unfolding over 17 years.

However, a remarkable story of restoration and reimagining is now being written. As of late 2025/2026, Haramaya is not just back; it is being strategically positioned as a cornerstone for economic development and a premier tourist destination. This isn’t merely a recovery; it’s a metamorphosis.

The catalyst for this shift is a multi-faceted, concerted effort spearheaded by the Oromia Regional State. As highlighted by officials like Culture and Tourism Bureau Head Jamiila Simbiruu and Mayor of Mays City Dr. Ifraha Wazir, the mission has moved far beyond refilling the lake. The goal is to systematically develop and promote Haramaya’s immense historical and natural potential. Having already achieved regional recognition, the focus is now on elevating it to a site of national significance.

The restoration itself is a testament to community-powered environmentalism. The lake’s return is credited to intensive rehabilitation works, including silt clearance and watershed management, combined with the transformative “Asheara Magarisaa” (Green Legacy) initiative. This involved the active participation of communities from 14 surrounding villages, turning a top-down directive into a grassroots movement for revival.

But the vision extends far beyond the shoreline. Authorities report that the lake’s volume and fish stocks are increasing year on year. Crucially, the perimeter is being secured, cleaned, and developed to unlock its full economic potential. An initial access road has already been completed, and a larger recreational project is underway along the banks, signaling a commitment to creating sustainable infrastructure for both visitors and the ecosystem.

Perhaps the most significant shift in strategy is the move from purely government-led action to a model seeking robust public-private partnership (PPP). Dr. Ifraha explicitly noted that unlocking Haramaya’s full potential requires significant investment from the private sector. This is already materializing, with 19 tourism-focused investment projects approved, nine of which are set to be built directly on the lakefront.

The ambition is grand. As the largest lake in Eastern Ethiopia, Haramaya is poised to serve not just Mays City but a wide region. It is envisioned as a major revenue generator and a source of employment, particularly for the youth. Its influence is rippling outward, with the production of lakeside ornamental plants now supplying major cities like Dire Dawa and Jigjiga.

In summary, the narrative around Haramaya has been fundamentally rewritten. It has transformed from a cautionary tale into a beacon of ecological recovery and smart economic planning. From being a place Ethiopians mourned, it is now a site they can visit and enjoy. With intensified efforts to enhance tourist services and attract more domestic and international visitors, Haramaya stands as a powerful testament to what can be achieved when environmental restoration is seamlessly integrated with community engagement and visionary economic development. The lake that was lost has been found again, and it is now working for its people.

Domestic Tourism: Reviving Oromo Culture in Maya

Feature Commentary: The “Domestic Tourism” Drive – More Than Just A Sightseeing Trip

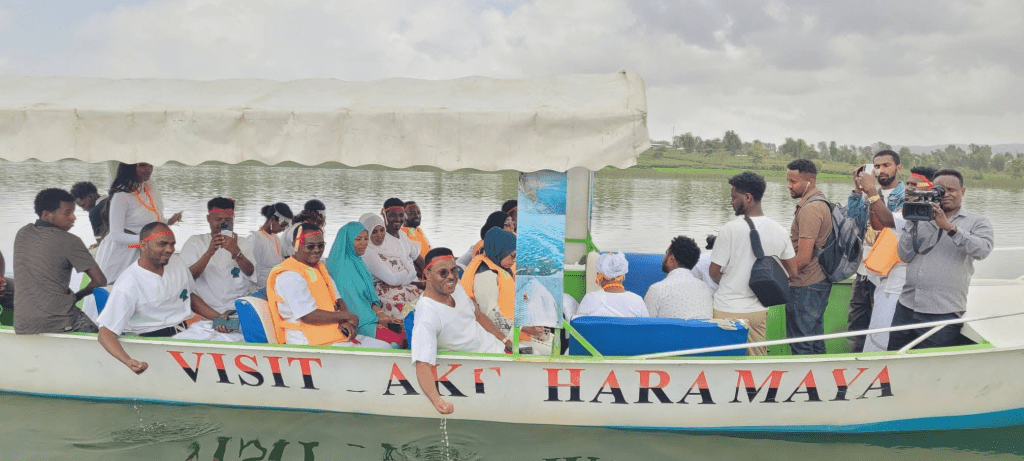

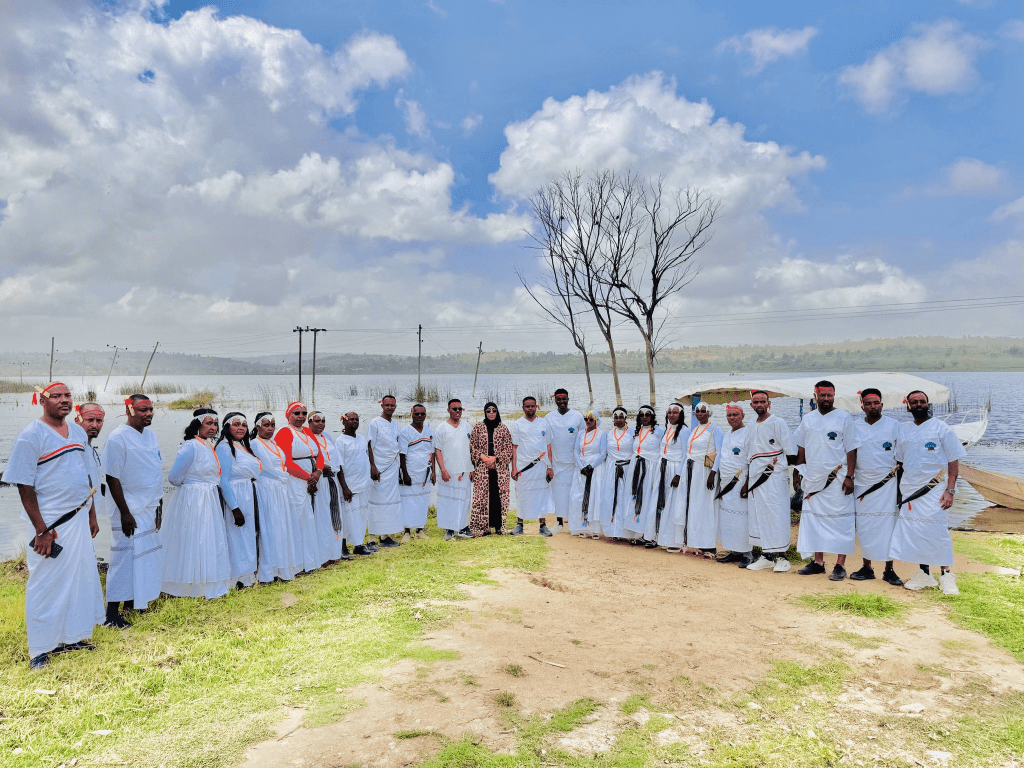

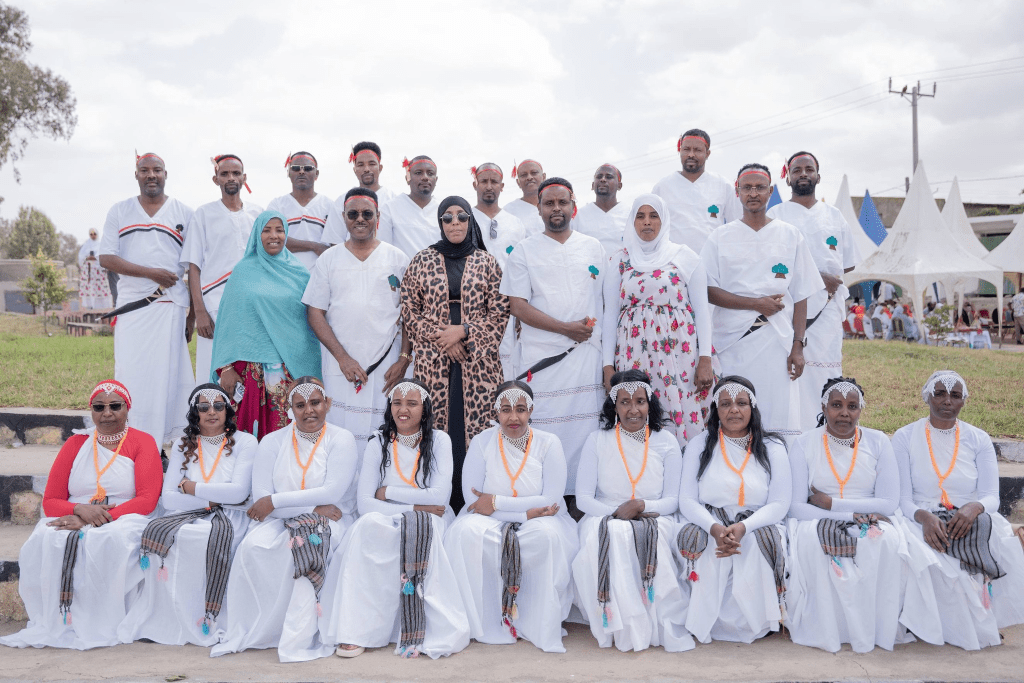

The successful conclusion of the domestic tourism promotion event in the city of Maya, East Hararghe, represents a significant and multifaceted stride for the Oromia Region. On the surface, it was a program where a delegation visited historical, cultural, and tourist sites. But to see it merely as a familiarization tour is to miss its profound cultural, economic, and social implications.

This initiative is a cornerstone of the Oromia Regional Government’s broader Cultural Renaissance policy. That term, “renaissance,” is crucial. It signifies not a static preservation under glass, but a dynamic revival—a reawakening. The goal is not simply to catalog old artifacts, but to actively safeguard, teach, and celebrate the rich and noble elements of Oromo culture. As the commentary notes, this ensures that “the younger generation knows its identity in the morning.” This metaphor is powerful: cultural knowledge is the dawn that illuminates who we are, providing direction and purpose from the very start of life’s journey.

The focus on domestic tourism is a masterstroke in this renaissance. It serves three interconnected purposes:

- Economic Activation: By extensively promoting Oromia’s tourism wealth, the program seeks to stimulate local economies. It encourages spending within the region, supports local guides, hospitality services, and artisans, and fosters community-based tourism. Strengthening domestic tourism builds a resilient internal market before even looking outward.

- Civic Participation: The program aims to “increase the involvement of relevant bodies.” This is about building a coalition for cultural stewardship—engaging local administrations, community elders, youth associations, and entrepreneurs. When communities see their heritage valued and visited, they become its most passionate curators and beneficiaries.

- Social Cohesion and Unity: Perhaps the most profound impact lies here. Visiting different areas within Oromia and Ethiopia breaks down internal barriers. It fosters a deeper understanding of the nation’s diverse tapestry from within. Shared experiences at historical sites and cultural ceremonies build a stronger sense of national unity and social solidarity. As stated, it “plays a high role in fostering the country’s socio-economic development and strengthening national unity.”

The choice of Maya and East Hararghe is itself symbolic. It directs the spotlight to the unique cultural and historical landscapes beyond the usual hubs, ensuring a more equitable and comprehensive celebration of Oromia’s heritage.

In essence, this domestic tourism drive is far more than a promotional trip. It is:

- A classroom for cultural identity.

- An engine for localized economic growth.

- A workshop for building social cohesion.

- A practical manifestation of the Cultural Renaissance in action.

The “milkaa’ina” (success) of the Maya event, therefore, is not just in its logistical execution, but in its powerful reaffirmation that understanding and exploring one’s own backyard is the first and most vital step toward sustainable development, cultural pride, and national unity. It sets a compelling precedent for other regions to follow, turning the nation into a classroom of mutual discovery for its own people.

Honoring Aadde Beernaadiit: A Legacy of Love and Resilience

A Feature Commentary: The Passing of Aadde Beernaadiit

The news of the passing of Aadde Beernaadiit, the widow of the renowned Oromo artist Dr. Hayilee Fidaa, marks the closing of a profound chapter in Ethiopian cultural and personal history. The memorial service planned in her honour is not merely a funeral; it is a testament to a life of resilience, deep love, and quiet strength that withstood the tremors of national tragedy.

Her story with Dr. Hayilee Fidaa is the stuff of a poignant romance. They met as young students in 1964 at a student event on Boulevard Jordan in Paris, a meeting of minds and hearts far from home. Their bond, formalized in marriage in 1966 in the U.S., flourished with the blessing of two daughters, Saraa and Yodit. This was the beginning of a family life built on intellectual companionship and shared dreams.

Then came the seismic event that would define the rest of her life: the assassination of Dr. Hayilee Fidaa in 1970. The commentary notes a harrowing detail: she learned of her husband’s murder while still in France, the country of the perpetrator. Yet, what did she do? She did not retreat. She embarked on a “great effort” to return to Ethiopia, to the very place where her husband’s blood was spilled. This act alone speaks volumes about her character—a determination to confront grief at its source, to be present in the land he loved, and to raise their daughters connected to his roots.

Her subsequent interviews, like one with Azeeb Warquu on Radio Fana, reveal a woman who, though devastated, framed her loss through the lens of the immense love they shared and her faith. She carried not just grief, but the weight of his legacy. Her dedication to Dr. Hayilee’s family—visiting his birthplace in East Welega, supporting his siblings and mother, educating his nieces and nephews—shows she became the living bridge between his past and their future. She didn’t just mourn an artist; she nurtured the ecosystem from which he sprang.

Her life in Addis Ababa thereafter was a powerful statement. Choosing to live in Finfinnee (Addis Ababa), the capital of her husband’s homeland, over France, demonstrated where her heart and loyalty lay. She channeled her experience into compassion, founding the “Okay” Charity to support orphans and women in distress. This was her enduring response to tragedy: not bitterness, but organized kindness.

The later years brought a familiar diaspora narrative—a daughter abroad, and the quiet life of an elder. Passing at 84, she witnessed epochs change, but her core identity remained: the guardian of a memory, a philanthropist, and a matriarch.

Therefore, this memorial service, this Yaadannoo fi Dungoo, is for so much more than a bereaved widow. It is for:

- A pillar of resilience who stood firm after an unimaginable blow.

- A keeper of the flame who diligently preserved and honored her husband’s legacy and family.

- A compassionate builder who translated personal pain into public good.

- A symbol of transnational love and loyalty, tethered between two worlds but choosing to plant her heart in Ethiopian soil.

Aadde Beernaadiit’s life reminds us that behind every great, lost figure, there are often unsung heroes of remembrance. Her strength ensured that Dr. Hayilee Fidaa’s legacy was not just a public treasure, but a lovingly tended private garden. In mourning her, we also honour the quiet, formidable power of the love that outlasts even death. May she find the peace she so steadfastly cultivated for others. #AaddeBeernaadiit #HayileeFidaa

Dr. Trevor Trueman: An Icon of Oromo Advocacy

Dr. Trevor Trueman (Galatoo): The Quiet Ally and the Unyielding Echo

Some names are woven so deeply into the narrative of a people’s struggle that they become inseparable from it, transcending geography, ethnicity, and origin. Dr. Trevor Trueman—affectionately known as Galatoo, “Thank You”—is one such name. His story is a powerful commentary on the nature of true solidarity, the enduring power of bearing witness, and the quiet, strategic work that sustains a freedom movement far from the headlines.

Dr. Trueman’s journey with the Oromo people began not in the halls of advocacy, but in the gritty, desperate reality of survival. In the late 1980s, as a family health physician, he was in Sudan, training Oromo health workers in refugee camps. When the Derg fell in 1991, he moved into Wallagga, shifting his focus to training community health workers. This foundation is crucial. His alliance was not born of abstract political theory, but of humanitarian connection—of seeing, firsthand, the people behind the cause. He didn’t arrive as an activist; he became one through service.

It was from this ground-level view that his pivotal role emerged. Starting in 1992, he began the critical, dangerous work of documenting and internationalizing the Ethiopian government’s systematic human rights violations against the Oromo people. While the OLF and others fought on the political and military fronts, Dr. Trueman opened a vital front in the global arena of information. He understood that a tyranny thrives in silence and that the world’s conscience must be awakened with evidence. His reports became the credible, external voice that the diaspora and activists within could amplify, forcing the “Oromo question” onto agendas where it was being ignored.

His strategic genius is perhaps best embodied in the Oromia Support Group (OSG), which he co-founded in 1994. The OSG was not a protest group but a clearinghouse for truth. It methodically gathered testimony, verified atrocities, and funneled this information to UN bodies, foreign governments, NGOs, and media outlets. For decades, when the Ethiopian state dismissed accusations as rebel propaganda, the OSG’s meticulously documented reports stood as unassailable counter-evidence. Dr. Trueman became a bridge of credibility, translating the suffering of a distant people into a language the international system was compelled, at least, to acknowledge.

This commentary highlights several profound truths:

- The Outsider as Essential Insider: Dr. Trueman’s identity as a “foreign national” was not a barrier but a unique asset. It lent his documentation an perceived objectivity that was desperately needed to break through global apathy. He wielded his privilege as a tool for the voiceless.

- Advocacy as a Marathon, Not a Sprint: His commitment, spanning from 1988 to the present day, defines “umurii dheeradhaa”—a long life of dedication. While political fortunes and rebel movements evolved, his channel of advocacy remained constant, providing a thread of continuity through decades of struggle.

- The Strategic “Taphat” (Preparation): The tribute rightly notes he will be remembered for his “shoora taphataniif”—his strategic preparations. His work was the essential groundwork. By ensuring the world could not plead ignorance, he created the political space and pressure that empowered all other facets of the Oromo struggle.

Dr. Trevor Trueman’s legacy is a masterclass in effective international solidarity. He did not seek to lead the Oromo struggle; he sought to amplify it. He did not fight with weapons, but with words, facts, and an unwavering moral compass. In the grand symphony of the Oromo quest for freedom, if some voices are the roaring melodies and others the steady rhythm, Dr. Trueman’s has been the crucial, clear note of the witness—persistent, truthful, and cutting through the noise to make the world listen.

For this, the name Galatoo is not merely a token of thanks, but a title of honor, earned over a lifetime. His work ensures that the crimes committed in darkness are recorded in light, and that the struggle of the Oromo people has, indeed, been given an echo the world cannot un-hear.

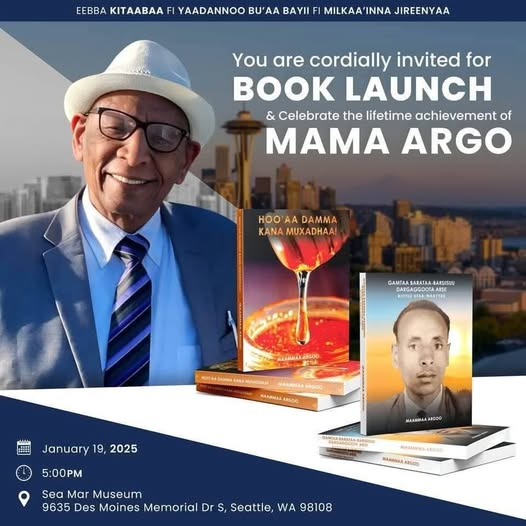

Mammaa Argoo (1946-2026): A Legacy of Service in the Oromo Struggle

A Life of Unwavering Service: Mammaa Argoo and the Enduring Spirit of the Oromo Struggle

The passing of Obbo Mammaa Argoo in Seattle, USA, is not merely the loss of an individual, but the quiet closing of a chapter written with relentless dedication. His life story, woven from threads of professional service, community building, and unwavering support for the Oromo cause, stands as a powerful commentary on the nature of true activism and the quiet architects of diaspora identity.

Obbo Mammaa’s journey defies the simplistic narrative of a revolutionary who arrives fully formed. It reveals a more profound truth: that the backbone of any long-term struggle is often built by those who work without fanfare, whose “front line” is the community meeting, the weekend language class, and the patient effort to explain a people’s plight to the outside world. From his early days in the 1960s in Shashamane, where he worked to expand educational access in rural villages, to his decades as a respected healthcare professional in Ethiopia and later in Seattle’s Harborview Medical Center, his foundational principle was service.

This ethos seamlessly translated into his life in diaspora. Upon arriving in Seattle in 1992, he didn’t retire; he re-planted his roots in service. He became a pillar of the Oromo community there, not as a distant figurehead, but as a hands-on organizer. For 27 years, he served tirelessly. The establishment and nurturing of the Oromo Sports Federation in North America (OSFNA) is a testament to his visionary understanding that cultural unity and physical well-being are vital for a dispersed people. The weekly classes he helped lead—teaching Oromo language, history, and culture to children—were an act of profound resistance against assimilation and oblivion. These were the quiet trenches where identity was fortified for the next generation.

His engagement extended far beyond the Oromo community. His service on boards like the Harborview Community House, the East African Advisory Council for Seattle Police, and One America illustrates a crucial point often missed: effective advocacy for one’s own community requires building bridges and understanding within the wider society. He knew that to advance the Oromo cause, he had to be a respected voice in the broader conversations about human rights, immigration, and civic participation. He was a connector, translating Oromo realities for American institutions and leveraging those institutions for the benefit of his people.

The commentary of his life makes several indelible arguments:

- Activism is Multifaceted: The freedom struggle is not fought only with political manifestos. It is fought in hospitals with compassionate care, in sports federations that foster pride, and in classrooms on Saturday mornings where mother tongues are kept alive. Mammaa Argoo embodied this holistic approach.

- The Diaspora as a Foundation: He demonstrated that the diaspora’s role is not just to lobby or send remittances, but to build sustainable, enlightened, and united communities abroad. These communities become enduring repositories of culture and platforms for advocacy.

- Steadfastness Over Spectacle: In an age of fleeting headlines and performative activism, his nearly three decades of consistent, granular community work—“without rest or break,” as the tribute notes—speaks of a deeper, more resilient commitment. His was a long obedience in the same direction.

- The Personal is Political, The Professional is too: His career in healthcare was not separate from his activism; it was an extension of it. Caring for the sick, whether in Bulbula, Adama, or Seattle, was congruent with caring for the health and wholeness of his nation.

Obbo Mammaa Argoo has now “left this world,” as the tribute respectfully states. But he did not leave a void; he left a blueprint. He was a man who, as his story confirms, “did not turn his back on the Oromo struggle,” but rather folded it into the very fabric of his daily life, his profession, and his civic duty. His legacy is not etched in stone monuments, but in the living institutions he helped build, in the children who can speak Afaan Oromoo, in the stronger community fabric of Seattle, and in the powerful, quiet example of a life spent entirely in the service of others.

His passing is a moment of sorrow, but more so, it is a moment for reflection on what enduring commitment truly looks like. It looks like the life of Mammaa Argoo.

The Legacy of Obbo Mama Argo: A Community’s Guiding Star

The Milk of Human Kindness: On Losing a Local Legend Like Obbo Mama Argo

By Dhabessa Wakjira

True community is rarely built in grand gestures announced with fanfare. More often, it is woven in the quiet, repeated acts of welcome that happen after dark, in the glow of a porch light, in the simple offering of a cool drink. The passing of a figure like Obbo Mama Argo of Seattle reminds us that the mightiest pillars of a diaspora are often the most humble, their legacy measured not in headlines, but in the cherished, personal memories of a generation.

News of his departure arrives, as the community member writes, with “great sorrow.” But the obituary that follows is not a formal listing of titles—though he certainly earned them as a founding pillar of the Oromo Soccer Federation and Network in North America (OSFNA) and a selfless public servant. Instead, it is something more powerful: a flood of sensory memory, a testament to a man whose impact was felt in the intimate, daily fabric of life.

“I can’t think of anyone who was more selfless or whose contributions are more undeniable,” the tribute begins, anchoring his legacy in collective agreement. For over twenty years in Seattle, the writer explains, “we grew up looking up to his guidance and the love he had for Oromos.” Here is the core of it: he was a local north star, a constant reference point for a community finding its way in a new land.

Then comes the defining anecdote, the story that paints a clearer picture than any official biography ever could. “Back in those childhood days… every evening after soccer, we would go to his house and drink milk.” From this simple, nurturing act emerged his most beloved title: “Abbaa Aannanii” – the Father of Milk.

This name is a masterpiece of community poetry. It speaks of sustenance, of care, of a home that was always open. It speaks of a man who understood that building a community isn’t just about organizing tournaments or holding meetings; it’s about feeding the youth, literally and spiritually. His house wasn’t just a residence; it was a post-game refuge, a cultural waystation where ties were strengthened not through rhetoric, but through shared cups and shared presence.

The tribute makes a profound point about gratitude: “This blessing was a great reward that the Seattle community received from him. Receiving it was timely.” Abbaa Aannanii performed his essential role precisely when it was most needed—during the formative years of a community’s establishment. His gift was his unwavering, predictable kindness.

And so, the writer issues a crucial, poignant reminder: “It is necessary to say THANK YOU to people like him while they are still alive.” We are often so good at eulogizing, at weaving beautiful galatoomaa in hindsight. But the true challenge is to offer that gratitude in real-time, to honor the living pillars before they become memories.

Obbo Mama Argo’s story is a universal one. Every community, every neighborhood, has its Abbaa Aannanii—the person whose door is always open, whose quiet support forms the bedrock. His passing is a deep loss precisely because his contribution was so profoundly human. He built a nation not through pronouncements, but through poured cups of milk; not just through organizing soccer, but by ensuring the children who played it were nourished, welcomed, and loved.

His legacy is the warmth of that remembered milk, the strength of the bonds forged in his living room, and the enduring model of a patriotism expressed through radical, open-hearted hospitality. We extend our deepest condolences to his family, the Seattle Oromo community, and OSFNA. In mourning him, may we all be inspired to see, appreciate, and thank the quiet pillars in our own midst, while the light on their porch is still on.

An Unseen Architecture: The Passing of a Pillar and the Foundation He Leaves Behind

An Unseen Architecture: The Passing of a Pillar and the Foundation He Leaves Behind

By Maatii Sabaa

A community, especially one woven across a diaspora, is an intricate architecture. We most easily see its public face—the vibrant festivals, the spirited tournaments, the collective statements. But the integrity of the entire structure, its ability to stand firm across distance and time, depends on a different kind of element: the hidden pillars. These are the individuals whose work is not in the spotlight, but in the scaffolding; whose legacy is not a single dramatic act, but the relentless, humble labor of holding things together.

The recent passing of Obbo Mama Argo is the quiet removal of such a pillar. The condolences flowing to his family, the Seattle Oromo community, and the Oromo Soccer Federation and Network in North America (OSFNA) speak to a loss that is deeply personal yet irreducibly public. He is remembered with the profound titles that form the bedrock of any strong society: a devoted patriot, a loving family man, a selfless public servant. But it is the specific mention of his founding role in OSFNA, and his three decades of support for it, that reveals the true nature of his contribution.

To found an organization like OSFNA is to do more than start a sports league. It is to recognize that for a dispersed people navigating the complexities of a new world, identity needs a living, breathing, communal space. A soccer tournament becomes more than a game. It is an annual pilgrimage, a temporary capital, a network of kinship and care. It is where the next generation meets the old, where news is exchanged, where culture is performed, and where a scattered nation gathers to feel whole.

For three decades, Obbo Mama Argo helped build and sustain this sacred space. This was not a ceremonial role. It is the unglamorous work of logistics, diplomacy, fundraising, and quiet encouragement. It is resolving disputes, securing fields, comforting losses, and celebrating victories that extend far beyond the final whistle. It is the work of a builder who understands that the structure—OSFNA—is not an end in itself, but a vessel for preserving something infinitely precious: a sense of belonging.

His type of patriotism is the most essential kind. It is not the patriotism of grand rhetoric, but of concrete action. It is the patriotism that shows up, year after year, to ensure the community has a place to play, to connect, to be Oromo together in a foreign land. This “selfless public service” is the very glue of diaspora survival.

In mourning him, the community confronts a poignant truth. We often celebrate the visible leaders—the speakers, the stars, the officials. But the true resilience of a people is forged by those like Obbo Mama Argo, whose life’s work was to be a reliable constant, a foundational node in the network. His absence creates a silence that is less about noise and more about stability; a space where his once-steadfast presence used to be.

The greatest tribute to such a man, therefore, is not just in the tears shed, but in the continued strength of the architecture he helped build. It is in the ongoing vibrancy of OSFNA, in the unity of the Seattle community, and in the commitment of new generations to step into the supporting roles he exemplified. To honor Obbo Mama Argo is to understand that the most enduring monuments are not made of stone, but of sustained, loving effort. His legacy is etched in every game played, every connection made, and in the enduring sense of home he helped construct for a nation far from its geographic one.

Galatoomi, Abbaa Argo. Your foundation holds.